December 2012

This report, written by senior fellow and former Rockefeller Institute Director Richard P. Nathan, puts forth a package of ideas for next steps in reining in health care costs. As President Obama might put it, high health care costs are not a liberal or conservative problem, nor are costs a public or private sector problem. They are an American problem, one that is manifest throughout the nation’s health care system. The very high costs of health care in the U.S. not only contribute to the fiscal problems faced by American governments and squeeze many other public functions, they also increase the costs of labor and business and may diminish the nation’s economic inclusion and competitiveness.

Nathan says his proposals are incremental, and that is true in the sense that all of his recommendations involve approaches currently used somewhere in U.S. government. His suggestions are distinctive, however, in the way they would extend certain ideas across a larger part of the health care system — and thus reduce some of the differences between Medicare, Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and even employer-sponsored insurance. He would, for instance, expand the use of market-based exchanges — a key element in the ACA — within Medicare. He would shift the responsibility for operating exchanges under the ACA, now primarily a state function, to the federal government, as is the case under the Medicare Advantage plan. He would encourage insurance plans with significant copays, health savings accounts, and catastrophic health insurance within the ACA as well as among private employers.

In general, he promotes consumer choice — and consumer exposure to some, but not catastrophic, levels of health care costs — throughout much of the insurance system, public and private. And he sees the federal government as the appropriate level for most of the public responsibilities. The paper ends by presenting ideas on “how we might get from there to there,” both in making next-step decisions and implementing them. In the latter case, the paper suggests a phased/adjustable approach that builds on experience of things that we don’t know yet. Nathan draws on his deep understanding of government in proposing a process that skeptics of the capacity of government leaders to anticipate problems of politics and implementation can appreciate. Not everyone in the field will agree with the ideas presented here, but this surely is the time to look at ideas like this, both in terms of substance and process.

“I believe we have to continue to take a serious look at how we reform entitlements, because health care costs continue to be the biggest driver of our deficits.”

President Obama, Press Conference, November 14, 2012

America has a health care cost crisis. It will take at least one more round of health care reform to fix it. Listen to the experts; look at the data.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, who worked in the White House on President Obama’s 2010 national health reform law, said, “If you have heard it once you have heard it a hundred times. ‘The United States spends too much on health care.’ This is not a partisan point.”1 Peter Orszag who directed both the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and later the Office of Management and Budget during the formation of President Obama’s health reform plan, said, “It is no exaggeration to say that the United States’ standing in the world depends on its success in constraining this health care-cost explosion; unless it does, the country will eventually face a severe fiscal crisis of crippling inability to invest in other areas.”

According to the Simpson-Bowles commission on deficit reduction, “Federal health care spending represents our single largest fiscal challenge over the long run.”3 Princeton Economist Alan Blinder, formerly vice president of the Federal Reserve and a member of the Council of Economic Advisors, put it this way: “The myth is that America has a generalized problem of runaway spending. No. The truth is that we have a huge problem of exploding health-care costs, part of which shows up in Medicare and Medicaid.”

Taken together, Medicare and Medicaid account for 25 percent of federal spending; they are projected to account for one-third in 2021. Medicaid also accounts for a huge and growing share of state budgets, and in some states local budgets as well.

Focusing on Medicare, Jonathan Gruber estimates that in order “to put the program on a solid footing for the foreseeable future would require imposing a 15 percent payroll tax. Every person in America would have to pay 15 percent of their wages to the government, basically doubling the tax burden on American families.

The 2011 annual report of the Medicare Trustees was pessimistic about the country’s ability to deal with cost pressures. Based on past experience, the Trustees urged readers to recognize the “great uncertainty” associated with achieving scheduled reductions in physician’s fees and cost-reducing measures in the 2010 national health reform law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).

An analysis by Eugene Steuerle of the Urban Institute shows the share that Medicare taxes and premiums cover “of the care provided to the average recipient ranges from 51 to 58 percent over time.” Steuerle says “[for] the rest we borrow from China and elsewhere, and we use up ever-larger shares of income tax revenue, leaving ever-smaller shares for the government functions. Bottom line: without reform, current workers would continue to shunt many of their Medicare costs onto younger generations.”

For Medicaid, the annual increase in spending from 2000 to 2011 was 7.1 percent, driven by annual enrollment growth of 4.6 percent and medical price inflation plus benefit increases estimated at 2.5 percent. This is 3.2 percentage points greater than the total annual growth in state tax revenues in this period.

An article on Medicaid published in Health Affairs focusing on cost estimation was entitled, “Policy Makers Should Prepare for Major Uncertainties in Medicaid Enrollment, Costs and Needs for Physicians Under Health Reform.” The authors estimated that the number of additional people enrolling in Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act could range anywhere from 8.5 million to 22.4 million, with estimated costs and physician needs reflecting a similar very large range of uncertainty.

Governments at all levels pay for about half of all health spending; employers, individuals, and charitable contributions account for the rest. On the broadest basis (including both private and public health care spending), the rate of increase in health care spending slowed in 2009 and 2010. Still, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), which provides the official data, reported an annual increase of 3.9 percent each year, which was over twice the rate of growth of the economy in the period. Moreover, CMS projects the rate will speed up in 2013 to an annual rate of 5.5 percent.

Health care currently accounts for 17.9 percent of America’s gross domestic product. This ratio is forecast to continue to rise and exceed 20 percent by 2018. Compared to other countries, this is a very high ratio. On the basis of the data provided by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the European average for the share of national health spending in relation to GDP was 7.9 percent, compared to 12.9 percent for the United States (using the OECD definition for making these comparisons). This situation exists despite the fact that European countries have universal, or near universal, health care coverage while in the United States private insurance and government programs leave one-sixth of the population uninsured.

Advocates of health care services tend to take the position that if we want more and better health care, it is acceptable for the total cost to continue to grow faster than inflation, the economy, and the tax base. But over the long haul, this is not sustainable. It puts tremendous pressure on taxpayers and crowds out other government programs.

Structural reform of the nation’s health care programs is necessary and unavoidable. We cannot sit back and hope economic forces now in play will produce a steady state condition in which everyone who needs care receives all the care they need under existing policies and programs.

It is not that as a country that we want to control health care spending. It is that we have to. There are two reigning theories of change for next-step health care reforms to address cost problems. One is the provider-value theory emphasizing government action to integrate services and in other ways increase the productivity, quality, and efficiency of care. It works primarily on the supply side of the economic. That is, it seeks to influence how providers behave. The other theory is the consumer-directed or consumer-choice theory. It works on the demand side. It seeks to leverage the power of consumers in making decisions about what they buy and how, and how much, they pay. Its emphasis is on giving consumers “skin in the game” giving them a tangible connection to the cost of their health care by empowering them to make wise choices in the health care marketplace.

Provider-value social engineering shouldn’t be the main line strategy for dealing with the fiscal imperative of fast-rising health care costs. Politicians are good at giving social benefits but not so good at taking them away. Likewise, leaders in government public health care programs tend to come to their jobs with a concern about and belief in the programs they are responsible for. Government does not have the necessary penetration — nor the leverage commitment, or clout needed — to reform the huge health care industry. The provider-value approach, relying on initiatives and experiments led by public agencies to reorganize health care, is the least promising of the two theories of change. In the long run, creating and managing competition in the health care marketplace is the better approach for achieving health care cost control by mobilizing price-consciousness in a way that at the same time protects consumers from having to pay the high costs of catastrophic care.

Based on a review of the literature and an analysis of current policies and programs, this paper argues that three types of reforms are needed: (1) strengthen market incentives, (2) place greater emphasis on income-testing, and (3) give priority to meeting catastrophic health care needs. What is recommended is an amalgam that builds on existing health care systems in ways that put consumers in a stronger position to make choices about what health care services to obtain and which of the health insurance plans offered to them are the best ones for them to select.

It is useful up front to present a summary that, while not fully defining each part, describes the major components of the consumer-choice amalgam for next step health reform this paper recommends:

In these four areas, the paper presents suggestions for a market-incentivizing regime for health insurance that brings together the aims and interests of the different organizations and groups that favor change in the way health care is financed and provided.

Doing this is not just a political or policy challenge; it is a management challenge of a high order. What kinds of structures and mechanisms would be needed to put a tourniquet on health care costs? And once decisions are made about how this should be. done, what kinds of processes should be used to get them adopted and put into effect?

On March 23, 2010, President Barack Obama signed what he wanted to have regarded as his signature legislative achievement, health care reform. He signed the bill at a White House ceremony, using twenty-two pens so he could give pens to major supporters. The law is officially the Patient Responsibility and Affordable Care Act, best known at ObamaCare. The President made this his top priority despite the fact that some of his closest aides did not want him to do so. But he persisted. Following the adage of striking while the iron is hot, the president geared up early to accomplish what so many before him had failed to achieve.

Although at the outset the term “ObamaCare” was used pejoratively by the law’s opponents, it has come into wide and general usage. Ultimately, the president, in a campaign debate, smilingly said “it’s growing on me,” indicating his willingness (in fact his pride) in using the popular name.

Despite the fact that throughout his first term the law was one of the hottest political issues, it shouldn’t be viewed as all that radical. In the typical way things happen in American politics, it was a compromise. When the dust had settled on the ObamaCare law, it emerged as a political deal where liberals obtained expanded coverage and the health care industry (and it is a very big industry) achieved objectives its leaders sought.

Most of all, what the deal did was keep private insurance companies in business — in fact expanding their market — in exchange for adopting a new regime (a new set of rules) for health insurance. Health insurers bought into the deal for their good reasons and in so doing took on new obligations. They will not be able to turn down applicants on the basis of pre-existing conditions. This is a big item that gets at what is referred to in the industry as “cherry picking” by insurance companies, favoring the healthiest customers. Also, insurance companies can no longer put a ceiling on benefits and they face a new requirement to extend the time period (up to age twenty-six) that dependents can stay on a family’s policy.

In these ways and others, a federalism shift has taken place, moving more responsibility for oversight of the health insurance marketplace to the federal government in a field in which states have traditionally been predominate. State health insurance commissioners still have a major role to play, but there now is a new balance. For a country that has a strong ethos of free enterprise, this is a sensible compromise and approach. Still, changes are needed in the ObamaCare law. There is reason to be skeptical about the down-the-road estimate that the law will be cost-neutral. But all in all, the new regime for health insurance represents a major step in the right direction.

The signing of ObamaCare marked a 100-year effort to add health care to the nation’s social safety net. In 1912 when Theodore Roosevelt ran unsuccessfully for the presidency on the Progressive Party line, its platform promised health care for Americans. The United States was already something of a late-comer to the party. The goal of universalizing health care in major industrial countries was first achieved under Chancellor Bismarck in Germany in 1883.

In the 1930s President Franklin Roosevelt was urged by his advisors, notably Labor Secretary Francis Perkins, to include health care in the 1935 Social Security Act. That law provided pension aid for the elderly, set up a system for workman’s compensation, and another for unemployment benefits. But FDR wouldn’t add health care. He is reported to have said, and history seems to have proved him right, that he feared the opposition of the American Medical Association could sink his New Deal program if he tried to overreach.

Decades later, at the end of World War II, the United Kingdom established its National Health Service under a Labor Party government headed by Nye Bevin. In the U.S., President Truman revived the issue in the late 1940s and early 1950s, advocating universal (or anyway, near universal) health care, though without success.

As it turned out, the passage of time has made the job of expanding health care coverage a harder job for America. Serious Congressional give-and-take about the passage of such a law resumed in the mid-1960s. At first, the emphasis was on expanding care for seniors; President Kennedy tried to do this but did not succeed. It was in 1965 after his election as president in his own right that Lyndon B Johnson pushed (really pushed!) to get Medicare and Medicaid through the Congress. He signed the law with a single pen in Independence, Missouri, at the home of Harry Truman and gave the pen to him. Medicare made coverage universal for seniors; Medicaid aids the poor and disabled.

Efforts to achieve universal reform stepped up in the 1970s. Under President Nixon, a proposal was advanced for near-universal health care that in many ways resembles President Obama’s 2010 Affordable Care Act. But Nixon’s plan never moved forward, sidelined along with other issues by the Watergate scandal. The next high adventure for comprehensive health care reform was the drawn-out 1993 planning process under President Bill Clinton to devise a reform proposal. Conducted by eight “cluster teams” and thirty-four “working groups” (involving some 600 people), when the process finally ended the proposal that emerged did not move forward. It caused a storm of criticism (sound familiar?) to the point where the majority leader of the Senate at the time, Democrat George Mitchell, told the White House it was dead.

In mid-term Congressional elections in 1994, the Republicans captured both houses of Congress. That was it for health reform under Clinton. But the beat went on. Pressure continued to mount.

In the Reagan-George H.W. Bush years, a law was enacted to provide catastrophic coverage for seniors. It was signed by President Bush but lasted a mere eighteen months before being repealed due to pressure from seniors about the fees and surtaxes they would face. Under President George W. Bush, a big change was made that is still in law, adding a drug coverage benefit to Medicare. Despite the demise of the Clinton health care reform, Democrats revived the topic in the 2008 presidential election campaign.

In debates among the major Democratic candidates for the nomination, two of the three — Hillary Clinton and John Edwards — proposed comprehensive health reform, including a mandate whereby individuals and businesses would be required to purchase insurance coverage. They said this is needed to create a large enough insurance pool to make broadened coverage affordable. Senator Barack Obama at the time opposed the mandate. But when he was elected president he changed his mind. The elusive purpose of providing near-universal health care coverage is now in law. Will it stick and if it does will it work? We need next to look at the law and how it was put together.

President Obama’s legislative strategy took a page from the Clintons’ book about what not to do. The president decided not to try to devise a full, detailed plan to send to the Congress, but rather to present goals and principles and press for action on a bipartisan basis.

His aim, and this was not original to the Obama planners, was to reconcile three key goals of health reform — access, quality, and cost. In a primer on this legislative process and its final product, the staff of the Washington Post covering the debate characterized the new law as being in keeping with the way policy and political bargaining is conducted in Washington. “For all its scope” the authors said it is “a relatively moderate and incremental document — evolutionary and not revolutionary. It does not seek to replace the country’s system of private health insurance with a government-run ‘single-payer’ system such as Canada’s — the ‘Medicare for all’ approach advocated by many American liberals for years but sharply opposed by insurers and many medical providers.”

Continuing and stressing incrementalism, the authors said the new law “will not dismantle or fundamentally alter the system of employer based insurance, as several alternative proposals would have done by tossing aside the tax-free treatment of employer benefits.”

In fashioning the law, time and effort were absorbed bargaining with interest groups to win concessions, first from the drug industry and then the insurance industry, as well as from liberal groups. It was a balancing act that resulted in more business for the health care industry in exchange for more regulation of their business practices.

The main aim of the law was to provide subsidies to poor and middle-income citizens on a basis that would be “affordable” in three ways. One was to be affordable to the newly covered citizens. Second, was to make the law affordable to the federal government. A complex set of rules and provisions were cobbled together that it was hoped would cause the Congressional Budget Office, the nation’s scorekeepers for legislation, to say the law was cost-neutral (which they did) — i.e., that it did not add to the national debt. The third meaning of “affordable,” as stressed above, is for the national economy as a whole.

It is reasonable in light of history to be skeptical about the new law’s affordability. As it turned out, CBO scored the law as saving money for the federal government, but such numbers are hard to work with. This is tricky analytical territory. Cost estimates tend to come in low for numerous reasons — inflation, demography, new programs and provisions added, etc. When Lyndon Johnson signed the Medicare law, he said it would cost $600 million a year, but a year later the House Ways and Means Committee estimated it would cost $12 billion a year in 1966. The estimated cost of Medicare in 2011 is $551 billion and for Medicaid $432 billion, though for Medicaid revised assumptions about the effects of the Affordable Care Act suggest this number could rise to as much as $615 billion.

The cost of the Affordable Care Act presents formidable unknowns as to the incentive effects the law will have, how key regulatory policies will be interpreted, how the machinery for implementation will function … and the list could go on. Berkeley Law Professor David Gamage, who served for two years as an ACA financial analyst in the U.S. Department of the Treasury, has written a lucid, in-depth description on many of these issues and questions. It is convincing of what we already know. Cost estimation is an art form; there are many brush strokes yet to be put on this canvas and yet to be deciphered.

Employers will face choices — whether, for example, to pay a penalty for not covering their lower-wage workers or offering a. high-benefit plan to all workers that in the case of lower-wage workers would exceed the income limit for insurance costs and make them eligible for what would be a much better deal for them to receive new ACA subsidized health insurance policies. In these and other areas, the way employers behave and regulations are issued, interpreted, and enforced (and maybe modified) could result in substantially exceeding the estimated costs of subsidies under the projections by the Congressional Budget Office. Gamage in his analysis also considers the incentive effects on individuals and families, whether to take a job that offers coverage or not to, whether to marry, whether to divorce. The deeper one digs. the more aware one becomes of the tenuousness of cost estimates. What follows is a quick summary of how the ObamaCare law works, or at least is supposed to work.

The first step is a requirement for all states to provide Medicaid benefits to people up to 133 percent of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL), which adds about fifteen million people to coverage. For many states, particularly conservative states that have been slow to extend and expand Medicaid coverage, this repre- sents a heavy lift.

Step two requires each state to establish a health insurance exchange by 2014 under which an estimated fifteen million low- and middle-income people will be provided subsidized coverage. If a state fails to set up an exchange, the default positions are that they can perform this function under a partnership arrangement with the federal government or in the alternative the federal government will operate the exchange in that state. Initially, the House of Representatives opted for a single national health insurance exchange providing “essential benefits” under “Qualified Health Plans.” However, as matters played out (with the election of Scott Brown to succeed Ted Kennedy in the Senate), the final version of the law followed the Senate version and assigned the responsibility for operating the new health insurance exchanges to the fifty states.

At the outset of the implementation process, the Obama administration finessed the provision for determining “essential” benefits for the newly added subsidized population. As the political season was heating up, this decision was delegated to the states along with their responsibility for operating health insurance exchanges.

This situation, while still unsettled, is administratively convoluted and conceptually confused. The biggest health insurance. companies are national. People move around a lot from state to state. In theory as well as in practice, the income-transfer function of government is generally regarded as appropriately assigned to central governments. It is hard to argue for as much policy and managerial reliance on the 50 states for new health insurance exchanges as appears to be envisioned by the Obama administration. Responsibility for the ACA new health insurance exchanges should be national.

Some parts of the Affordable Care Act fit in well with the consumer-choice theory of change, relying on managing competition in the marketplace to expand coverage and reign in health care spending. This applies especially to the exchanges to be established under the Affordable Care Act (indeed, this process is underway) on which newly covered low- and middle-income citizens choose the coverage plan that best fits their needs, situation, and risk tolerance.

This is a key transition point for going back to the theme stated at the outset about the two theories of change for next-step health reforms. One theory operates inside government to develop ways to make health care more efficient by overhauling and integrating service systems and endeavors to have the health care industry adopt these approaches, the supply side approach. The other theory of change works, not inside government, but on the outside — in the marketplace for services to influence demand by enhancing cost consciousnesses in a way that empowers consumers and providers to make wise choices. I believe managing competition in new ACA health insurance exchanges should be viewed and pursued in these terms. A story about what happened in the debate on the Clinton health reform plan helps make the point. In the course of the Clinton administration’s efforts in 1993 to develop its plan, then U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan emphasized what he called “Baumol’s disease,” by which he meant “the inevitable escalation of costs under labor intensive social programs.” In fact, Moynihan was so impressed with Princeton Economist William Baumol’s research on the difficulty of public agencies preventing “the spiraling of costs” under government subsidy programs that he arranged a luncheon for Baumol and Hillary Clinton to talk about Baumol’s theory.

Sometimes called the “cost disease,” Baumol’s theory originated in the mid-1960s in research he conducted with Princeton economist William Bowen showing the way classical economic theory that ties wages to labor productivity doesn’t always work. Their original study was on the performing arts. An example given is that the number of musicians needed to play a Beethoven string quartet is the same today as it always been. In a similar way for heath care, much of the cost emanates from one-on-one interaction between caretakers (physicians, nurses, and support personnel) and patients. In fact, some technological developments in medicine exacerbate the character of health care by requiring more and more elaborate one-on-one relationships and interactions.

Moynihan sought to alert Hillary Clinton to the dilemma this presents for health care reform, but at the luncheon he arranged for her to meet William Baumol she was not impressed. However, to placate the senator, an influential member of the Finance Committee and noted expert on social policy, Hillary Clinton arranged a follow-up meeting for Baumol with White Houser aides. They, too, didn’t buy. More importantly for the Clintons, this tactic didn’t get Moynihan on board as a supporter of President Bill Clinton’s health reform plan. In their book on the Clinton plan, Haynes Johnson and David Broder said of Moynihan: “He wouldn’t say so aloud, but he clearly thought the Clintons naïve in their approach, especially when they claimed that their reforms would produce great savings that would enable coverage to be expanded.”

Two important insights are involved here. One is economic. The other is political. Moynihan told Johnson and Broder that he based his doubt that the Clinton health reform plan could control health care costs on what was happening to the Medicaid program in New York State. In this case, Moynihan’s argument was about politicians and bureaucrats, the point being that the behavior of political and career officials in American government is antithetical to price restraint. Interest group politics add to the strength of this argument. And, in addition, providers of social services and interest groups and organizations committed to major social purposes like those advanced by the Medicaid program add to political pressures for program growth.

The way to view the question about how to constrain health care costs is whether government or the marketplace is best suited to deal with the condition Baumol emphasized about labor- intensive work being hardest to change and make more produc- tive. The connecting theoretical tissue is about agents of change, whether bureaucrats or marketers are more likely to create conditions that affect an industry like health care so its organization and methods become more efficient. Moynihan used his frustration about the Medicaid program in New York (indeed a big and obvious target) to carry his argument forward. At its inception in 1965, the Medicaid program to aid nonelderly groups was seen as something of an afterthought to the Medicare program for seniors.

As it turned out, the story of this part of the law — Title XIX of the 1935 Social Security Act16 — is one of major and rapid expansion, which Frank J. Thomson in his excellent study of the politics of Medicaid attributes to “the considerable ‘autonomy’ of government actors in the policy process.”17 Moynihan in his own inimitable way embellished the point. He told Johnson and Broder:

“Here I have it, sir, handing over charts and statistical analyses. Data. Documents for you. Medicaid doubled in eight years of the Reagan administration, then doubled again in four years of the Bush administration.”

Johnson and Broder described Moynihan as adopting his professorial role. They said he “arched his eyebrows, peered owlishly over his spectacles” and then said: “Assuming geometric progression, sir, what day is the day on which we reach the point when Medicaid doubles in one day?”

Thompson’s history of Medicaid, which he termed an “an intergovernmental colossus,” presents story after story of how elected politicians and government officials in federal and state agencies put meat on the bones of Moynihan’s political behavioral argument. While initially seen and often depicted as an antipoverty program, Medicaid became powerfully important as a middle-class program.

The bulk of its spending aids seniors and the disabled for institutional and home care. Medicaid payments account for nearly half of all payments for nursing homes. Thompson describes these services as benefiting the elderly and their children and in the same way the disabled and their otherwise presumably responsible relatives — in both cases assisting many people who are needy but not necessarily impoverished.

Inside the Washington policy process, an extraordinary policy entrepreneur, Democratic Congressman Henry Waxman, chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, stands out as a “tenacious and skilled” advocate. He led congressional efforts from 1980 to 1990 that “imposed nineteen directives on the states to expand Medicaid eligibility.”19 Many of these measures had wide appeal — for example, aiding pregnant women and children with Medicaid — but by far the most costly add-ons were for institutional care for the elderly and disabled.

At the state level, governors and state officials seized opportunities to go after Medicaid dollars. They developed ingenious ways to use these funds to offset state spending, in some cases covering the full costs of hospital and health care services. Eventually, the federal government closed loopholes that had allowed the most egregious examples of converting Medicaid into a revenue-sharing type program for state fiscal relief.

Within the health industry, temptations for game playing sometimes defy imagination, and very probably exceed the capability of government agencies to provide full and in-depth oversight and enforcement. Up-coding of services, ordering more tests (some of them in self-owned facilities), excessive consulting, overly frequent appointments — all add to the argument against government social engineering as the major strategy for cost constraint.

In the long run, history would appear to be on Moynihan’s side. There is reason to be leery of government promises to promote efficiency in social programs for all the reasons given — the labor intensity of many of services, the political reality that governments are better at giving than taking away, and the complexity of the health care industry. These arguments taken together undergird the position taken in this paper in favor of demand side/consumer-choice policies as the best approach for next-step reforms. In many marketplaces consumers can’t buy more than they can afford, but for health care consumers typically don’t directly pay for what they receive. Providers do not have to compete on the basis of cost. A good way to demonstrate what the consumer-choice theory can do to change this dynamic is in the next section examining the role of health savings accounts, a favored instrument of consumer-directed care.

Health savings accounts have been around for a long time; in recent years their use has expanded greatly. These accounts, which operate under federal law and regulations, are tax exempt and can be used by the holders to pay for health care services, including covering deductible and copay costs under health insurance policies and limiting out-of-pocket payments thus providing catastrophic health care coverage. In fact, it is required that health savings accounts be linked to what are called “High Deductible Health Insurance” policies. These policies provide catastrophic care insurance protection against the high costs of long-terms illnesses and serious accidents.

Actually, the name “high deductible” is misleading. The requirements of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service for the deductibles under these linked policies (so they can be tax-free) are not “high” — at least in my reading. They can be set by employers and insurance companies at levels appropriate to the varied needs of health savings account holders — that is, depending on their income level and whether they are hourly or salaried workers. There has been strong movement in recent years to promote this heath-savings approach.20 Such combined plans are offered by half of all large companies (those with over 500 workers), which represents a five-fold increase over the past five years.

At the same time this has been happening in many large businesses, workers in small businesses and government workers are also increasingly being offered linked health savings account catastrophic coverage options. In many instances these plans are promoted as less expensive — both for the people covered and also for their employers, including many hard-pressed governments (especially state and local governments) that employ the vast majority of the public workers. Many employers offer more than one health insurance plan to their employees in “exchange-type” health insurance systems for choice making. These offerings often include one or more savings account options to which usually both the employee and employer contribute. If the money accumulated in an employee’s health savings account is not spent in one year, it can be carried over to reduce out-of-pocket expenses in future years. This, according to the consumer-choice theory, gives employees an incentive for controlling their health care spending. They are ex-

posed to prices in the marketplace. Employers often encourage (sometimes strongly encourage) their workers to select these combined savings account-catastrophic care plans.

In effect, health savings accounts are a financial arrangement for cost sharing backed by catastrophic health care protection. In contrast, conventional health insurance guarantees a package of health care benefits. The linked savings-catastrophic approach is a “two-fer.”

The higher the deductible under these plans, the more favorable other policy costs can be for the consumer — for example, lower premiums and copays and a higher out-of-pocket limit on health care spending. The U.S. Internal Revenue Service sets rules for health savings accounts as to how much can be contributed and how these funds can be used. Current limits for annual contributions are $3,000 for individuals and $6,000 for families. The minimum allowable deductible for “High Deductible Health Insurance” (HDHI) policies are $1,200 for self-only coverage and $2,400 for families. The IRS also sets maximum levels for the combined value of deductibles and out-of-pocket expenses under these dual plans, now about $6,000 for an individual and $12,000 for a family.

There are many ways health savings arrangements can be structured. Often there are exemptions under employer-sponsored health insurance plans whereby preventive care and wellness services are provided “free” up front so that the costs of these services are not subtracted from the worker’s health savings account.

This can be thought of as a “wrap-around” approach. Your employer covers certain prevention and related types of good practices up front and you use your “saved” money for other health care expenses until your back-up catastrophic health insurance plan comes into play. One private insurer (Aetna) has publicized data based on the company’s experience showing that under these dual plans consumers tend to ask more questions, select services and treatments in ways that avoid duplication, and keep closer track of what they receive.

A story that reveals what can be at stake for employers with health savings accounts involves the General Electric Company (GE). GE has been a leader nationally in developing and promoting health savings accounts for its workers. It is one of the few large companies that puts its health plans online and actively promotes the health savings account-HDHI linked approach. At the same time, one of the major product lines for the company is medical imaging.

The Wall Street Journal reported on the dilemma this created for the company.22 The article said GE worked to put its 85,000 white collar workers “on high-deductible health plans in an effort to stem the growth of its U.S. health bills, which are now running $2.5 billion a year.” The plan worked, but turned out to produce “bad news for GE’s health care business, which is one of the world’s biggest makers of MRI machines and CT scanners.” The article, “GE Feels Its Own Cuts,” went on to say that other large employers have had the same experience with consumer-choice health insurance policies. As for GE, we are told, it is now diversifying its manufacturing into other health technologies. The point is not to be missed: Exposing consumers to choices affects how much and what they choose.

Martin Feldstein in a 2006 Health Affairs article warned of the danger of “excessive spending, because patients do not face the full cost of care at the time that decisions on health care are made.”23 Even on the part of government agencies, views like these have been expressed favoring a demand-side market (i.e., consumer-choice) approach to health care. In 2004, a joint report by the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice stated the point strongly: “The fundamental premise of the American free-market system is that consumer welfare is maximized in open competition — even when complex products and services such as health care are involved.”

It is further contended by advocates of consumer-choice health policies that an important benefit of increased reliance on savings plans is that they bring health cost data out of its mysteryland. By increasing transparency and encouraging workers to be cost conscious, they make costs more visible. Using health savings account money, you know what you are paying for. They are especially appropriate for initial and routine health services and for healthier and younger families. This raises a crucial point. Critics of health savings accounts note that this is not where the shoe pinches; the predominant health care cost pressures are a consequence of chronic illnesses and serious injuries.

Health savings accounts set a tone in the market place both for consumers and providers, the latter of whom it is presumed will help patients make cost-sensitive decisions. Like the campaign to stop smoking, over time such a strategy can change the public mindset. Nevertheless, while health savings accounts linked to catastrophic health insurance are increasing, this strategy for consumer-directed reform leaves us with broader policy questions for the marketplace.

Taken together, private employer-sponsored health insurance accounts for three-fifths of all coverage, although its proportionate share has been declining (but not a lot) in recent years. On the other hand, there is a tendency to think that the health care marketplace idea isn’t there yet for government. But that’s wrong.

There are many government systems that provide choices for consumers for health care on health insurance exchanges. Here are some examples.

Medicare Advantage (Part C) is the best place to begin in looking at future prospects for a stronger orientation to consumer choice health care under government health programs. Medicare Advantage plans are offered by a range of private and nonprofit health insurance providers and care networks. They are administered on regional exchanges (mostly online) by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). At the outset of Medicare Advantage in 1997, a decision was made to pay on average a 12 percent premium to insurers for these plans compared to the cost of “original” fee-for-service Medicare. The fact that this subsidy now is scheduled to be eliminated is an important development, which could change the program appreciably.

However, the biggest unknown for the future of health insurance exchanges in government is the hot potato political issue of what to do about proposals that the entire Medicare program operate through the payments of premium-supports.

As indicated, this would not be all that new. A rising proportion of Medicare recipients are already in Medicare Advantage plans where consumers choose online among exchange-listed options. In many places “navigators” assist newly eligible Medicare recipients, especially on the all-important initial choice between “original” fee-for-service Medicare and Medicare Advantage options. Their decision often hinges on costs. Medicare Advantage plans offer more benefits and lower premiums, deductibles, and copays and have a limited network of providers. Insurers have an incentive to form networks (mostly managed care or preferred provider groups), negotiate actively with providers on rates, and encourage interconnections among services (test, consultations, and treatment) on a basis that both enhances efficiency and makes life easier for the people served.

This is managed competition. In my county (Osceola County, Florida), there are fifty-seven varieties to choose from. They are rated on a five-star system. Five-star health insurance plans can be selected at any time during the year. Plans ranked at two stars or less are not listed as available to purchase online. There are glitches of course. In a real sense, this is a work in progress. But the information flow is formidable. It’s all there. Even though there can be a plethora of information online, there is an explanation of the rating system, a way to consult by phone to learn about regional choices and in most areas invaluable free navigational aide is available in person and online.

Often when the country is debating what do about a problem, changes are already taking place. This is happening in response to rising health care costs. There are many ways health insurance plans are being offered that increasingly send out cost-consciousness/price-awareness signals. This kind of signaling is manifest in the rising role of linked health savings accounts and catastrophic insurance plans. It is manifest, too, in the way insurers compete for Medicare Advantage customers under a transparent system: while there is a lot to take in, it is genuine and competitive — if you will, managing competition. There needs to be pricing standards of reference for assessing these plans, which could (as is now widely done) be based on “relative value units” for physicians’ care and Diagnosis-Related Groups for hospitals, which in both cases are currently existing measurement systems under study for revision and updating.

The marketplace is doing its job. Insurance companies are making changes in their policies and practices to win market share. Governments are doing similar things to manage competition as a way to rein in their spending on employee benefits.

To repeat (even though it should be evident), one can view these kinds of developments in varied ways. Program advocates can be expected to be unhappy. On the other hand, faced with growing concern about public debt and deficits other observers can view health policy changes like those discussed in this paper as unavoidable, but necessary.

Congressman Paul Ryan, chair of the House Budget Committee, and others who have put forward the idea of a Medicare full conversion to fixed premium support have talked clearly and openly about this — i.e., having a flat amount of support (at one point $8,000 per recipient and at another an amount tied to the second lowest available policy in a given geographic region) in some cases with an annual inflation adjustment added.

Managing competition as a theory and slogan for health reform tends to be viewed in theoretical terms, but not nearly enough, or deeply enough, in operational terms.

Critical operational questions are manifold: Who would administer a national system of exchanges that included a new premium-support health insurance exchange for Medicare and how would the system work? At the national level, the major candidate to do this is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. However, my view is to think the history, mindset, and culture of CMS are not right for managing full and fixed health insurance competition.

Many private employers, of course, already do this — that is, manage competition in offering health plans by what is known as “active purchasing”— selecting plans that have favorable prices, are transparent, dependable, and user-friendly. Can this be done for Medicare?

It is interesting and notable that in another health-policy arena in government, “active purchasing” has recently come into prominence, i.e., active purchasing on the part of state governments in their planning for new state health insurance exchanges under the Affordable Care Act.

The most well-known case at the state level where active purchasing has already been put into effect on scale is for the Massachusetts “Connector” for its “CommCare” (subsidized) component. A Georgetown University study reported the Connector has encouraged CommCare plans “to submit the lowest possible bids,” noting too that it “automatically enrolls a participant who fails to choose a plan into the lowest cost plan.” Moreover, in 2010, when the Massachusetts law allowed the Connector system to add new plans, the Georgetown report said state officials “worked hard to ensure Celticare’s participation, with an aim to expand members’ plan choices and leverage lower prices from the original four plans” authorized under the legislation establishing the Connector program.

Similarly, in California, the state legislature working on the establishment of the California Health Insurance Exchange under the Affordable Care Act is described as having “given the Exchange an active purchaser role, granting it the authority to selectively contract for coverage with qualified health plans.”

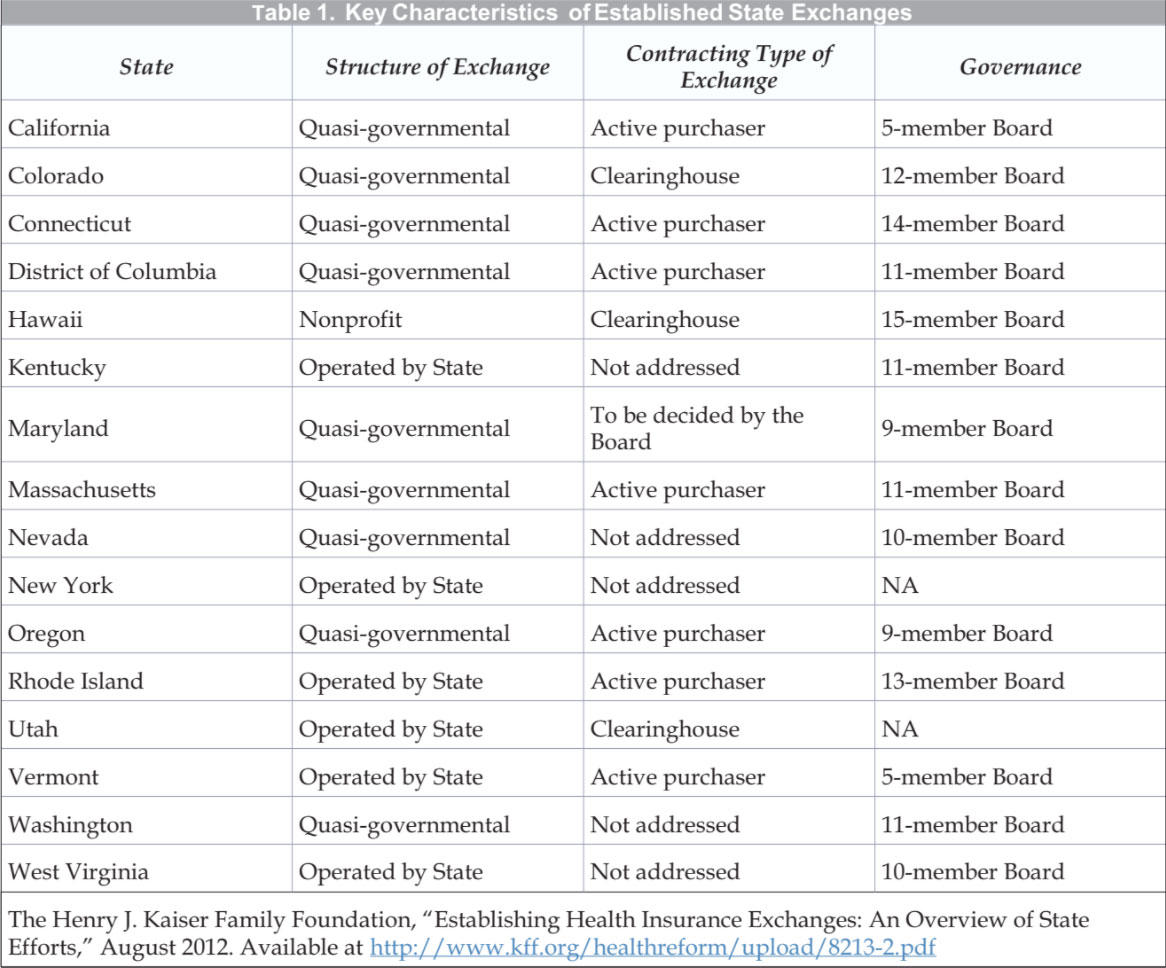

Looking at states across the board, an August 2012 summary by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that among fifteen states that at the time had made decisions about establishing a state exchange, seven had opted for active purchasing. Six states left open the decision of whether or not to adopt this approach. The Kaiser study found two states that opted for the “clearinghouse” approach under which all insurers who apply can offer policies.

There is a special pertinent question here for the Massachusetts Connector that applies as well to the planning for state exchanges involving the number of choices people should have. For Medicare Advantage, it is a big number, reflecting active market interest in competing for business. Reining in the number of offerings makes it easier for people covered to select a plan, and arguably puts state officials in a stronger position to negotiate with providers. But there is another side to this.

While individual insurance exchanges should be operated separately, they should be linked and similar in ways that take advantage of compatible organizational approaches and information systems to enable people to find out about their eligibility from any one of the systems and, in appropriate cases, to transfer from one exchange to another.

An overview board or commission could be the brain center for analyzing conditions, needs, system operations, and benefit programs and financial packages. It goes too far into particulars to do more than generalize about how this might work. Drawing on this central knowledge base and statistical capability, for example, the managers of the various exchanges could develop profiles of economic and health conditions and risk tolerances with the aim of offering a mix of plans that would fit the different profiled groups they serve. For the Affordable Care Act exchanges, modified health savings-catastrophic insurance options could be offered to middle-income eligible citizens, say above 200 percent of the federal poverty line, but not all eligible recipients. Likewise, for government workers, and even private employees benefited by the federal tax exclusion of employee health insurance, there could be a requirement to include health savings-HDHI options in the available mix.

These suggestions are illustrative. They are sketches. Building the administrative capacity for managing competition for health care is bound to be difficult and should be a learning experience. The ideas mentioned here indicate a direction for change and present suggestions for dealing with administrative challenges that have to be faced. Insurance regulation still is predominantly a state responsibility, although this is changing. For most purposes, health insurance policies are sold in state, not national, markets. This situation exists despite the fact that people frequently move from state to state and increasingly the number of insurers is diminishing as large companies become more dominant.

Managing competition on health insurance exchanges is not a job for an agency staffed by health experts. Market making and market oversight require multiple skill sets and workers. The federal and state boards and offices assigned to this function need to have health expertise, but just as much they need actuaries, statisticians, systems designers, enforcement and security experts, and management and communications specialists — combined in an organization that has substantive knowledge and strong systems’ management capability.

Typically, this is a job for a public authority or public enterprise with operating responsibilities rather than a government agency responsible for a functional area of policy. There should be oversight; the job is by no means apolitical. The responsible entity should have a status that blends neutral competence and political insulation on a day-to-day basis with policy accountability over the long haul.

A Health Care Review and Adjustment board or commission could have the responsibility for overseeing the operations and activities of component programs-area health insurance exchanges, monitoring their performance, assessing program costs and as necessary proposing adjustments in program goals and management systems.

Health reform is a metaphor for what’s wrong with American government in the information age. Agonizingly slow Madisonian decision making needs to be tempered and streamlined in inventive and politically savvy ways. In the health field, stakeholder views are fiercely held. There are pronounced differences between liberals and conservatives and between proponents of the provider-value and consumer-choice approaches to reform. It is a lot to wish for that there would be a moment when players gridlocked in this way could come together. Still, the postelection fiscal cliff exigencies of a $1.2 trillion budget sequester plus the need to raise the nation’s debt limit next year and the expiration of the Bush tax cuts occurring simultaneously could produce such a crisis moment for a fiscal grand bargain that includes goals for health program cost reductions.

The approach I suggest is incremental. It would require the kind of policy bargaining our political system does when it’s working best. It would be like a dinner menu that asks you to pick some things from column “A” and some from column “B” — both consumer-choice and provider-value reforms.

Hard as it would be after the election, the country, its pubic sector, and the national economy would be well served by setting up a process so health care reform positions could be examined together and hopefully reconciled in a way that involves multiple components, such as : (1) fixing the Affordable Care Act so there is a single unified exchange system and it has a built-in adjustment mechanism;28 (2) promoting and facilitating the widespread adoption of health savings accounts linked to catastrophic health insurance; (3) reforming Medicare along lines that build on Part C (Medicare Advantage) so it is a closed-ended, adjustable premium-support system that protects the most vulnerable people and at the same time strengthens income-testing; (4) reformulating and using the federal-state Medicaid program as the ultimate back-up for people below the Federal Poverty Line or below 133 or 138 percent of this line; (5) putting in place a fail-safe process for monitoring and adjusting this system; and (6) launching a “Manhattan Project” to unify and simplify health care information systems, including accounting and billing statements.

How could such a new regime be instituted and institutionalized?

A possible way to accomplish this would be under a multiyear process. The first step could be to establish an entity like the Simpson-Bowles deficit reduction commission to set out the principles, goals, and plans for administrative structures of a new system. This could take a year and include extensive consultative processes and a report to the president and the Congress.

This commission, for example, could consist of ten members (four appointed by the president, including the chair or co-chairs) and three each appointed by the leaders of the House and Senate. Members should not be current government officials or represent organizations. No more than two of the president’s appointees should be of the same political party; the same rule should apply to the appointees of the two bodies of the Congress.

Then, taking into account that if a new grand bargain for deficit and debt reduction has a long (say ten-year) time frame, the authorizing law could make provision for a second step to work out the devilish details in legislation based on the first-step plan and the reactions it engenders.

This second-step process for systemic legislative planning would have the time and should have the horses and the tools to prepare proposed reform legislation that would be considered in an expedited decision process. The president and the Congress within an allotted period of time could be empowered to approve the plan or send it back to be revised.

Such a process would provide time for deliberation and debate, although clearly they would require tense and intense negotiations. Critical decisions would have to be made about who would be involved; who would be the leaders; and what the mission, timetable, and auspices would be for their work. Moreover, these institutional arrangements should not be one-time. They should include provisions, not just for second-step systemic decision making, but also for refining and adjusting the new policy bargain over time.

Institutional invention like this, though unusual, would require political statesmanship of a high order. But even if it took two years (maybe three) to work out a new deal for health reform in conjunction with the next deficit-reduction package, it would be better to do this on a phased, adjustable basis than trying to enact full-blown new legislation in contentious rapid-fire budget negotiations.