September 2017

When the U.S. Congress passed the Supplemental Appropriations Act of 1993 in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew, it marked the first explicit use of Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funds for disaster recovery purposes (Gotham 2014). Since then, what has become the Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program has significantly expanded in amount and scope (Spader and Turnham 2014). Administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the program has emerged as a flexible supplement to other recovery programs directed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Small Business Administration (SBA), and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Typically, there are no regulations specific to the DR program; instead, DR funds derive most of their regulatory characteristics from the parent CDBG program. All CDBG (and CDBG-DR) funded activities must meet one of the three so-called national objectives: (1) primarily benefit low- and moderate-income (LMI) individuals and communities, (2) respond to an urgent need, or (3) prevent slum and blight (HUD 2002). What is known as the “targeting requirement” generally requires grantees to dedicate at least 70 percent of funds towards meeting the first objective (HUD 2002). In doing that, grantees must document that their activities have benefited LMI persons and/or businesses directly (“direct benefit”), targeted a population presumed by HUD to be LMI (“limited clientele”), or have benefited all the residents of an area determined to be LMI (“area benefit”). The latter approach is the focus of this paper. When grantees use area benefit, typically for community-wide activities such as infrastructure investments, they must define a “service area” that captures the activity’s primary beneficiaries (a town, school district, etc.). For the service area to meet the LMI objective, a certain percentage of the beneficiaries must be LMI.

Federal policymakers designed the parent CDBG program to increase individual and community resiliency by improving housing, economic development, and community assets (HUD 2002). CDBG-DR grantees are also required to demonstrate “a connection to addressing a direct or indirect impact of the disaster in a Presidentially-declared county” (HUD 2013). This geographic constraint — while eminently appropriate in the context of disaster assistance — may hinder grantees in disbursing funds to impacted communities while also meeting their overall LMI targeting requirement. This is because while general CDBG allocations are primarily based on the underlying demographics of an area (e.g., income), a disaster is blind to those characteristics. Some affected areas may have high LMI concentrations, and some may not. While grantees can design direct benefit recovery programs to specifically target LMI persons, their ability to document LMI investments using area benefit is more subject to those underlying demographics of the affected areas. And yet investments in repairing and strengthening community assets are critical to broader rebuilding efforts in the aftermath of a disaster, making them an important component of a DR grantee’s portfolio.

In most disasters, the LMI targeting requirement has remained at 70 percent of allocated funds, but federal policymakers have sometimes recognized the difficulty for grantees in addressing recovery needs while also meeting this requirement (GPO 2013). For example, Congress waived the requirement for New York State after 9/11 (GPO 2002). More recently, HUD lowered the requirement to 50 percent of allocated funds for both Katrina and Sandy grantees (see Section 2 for a detailed discussion). What is not clear is how and why federal policymakers decide on these alternative requirements.

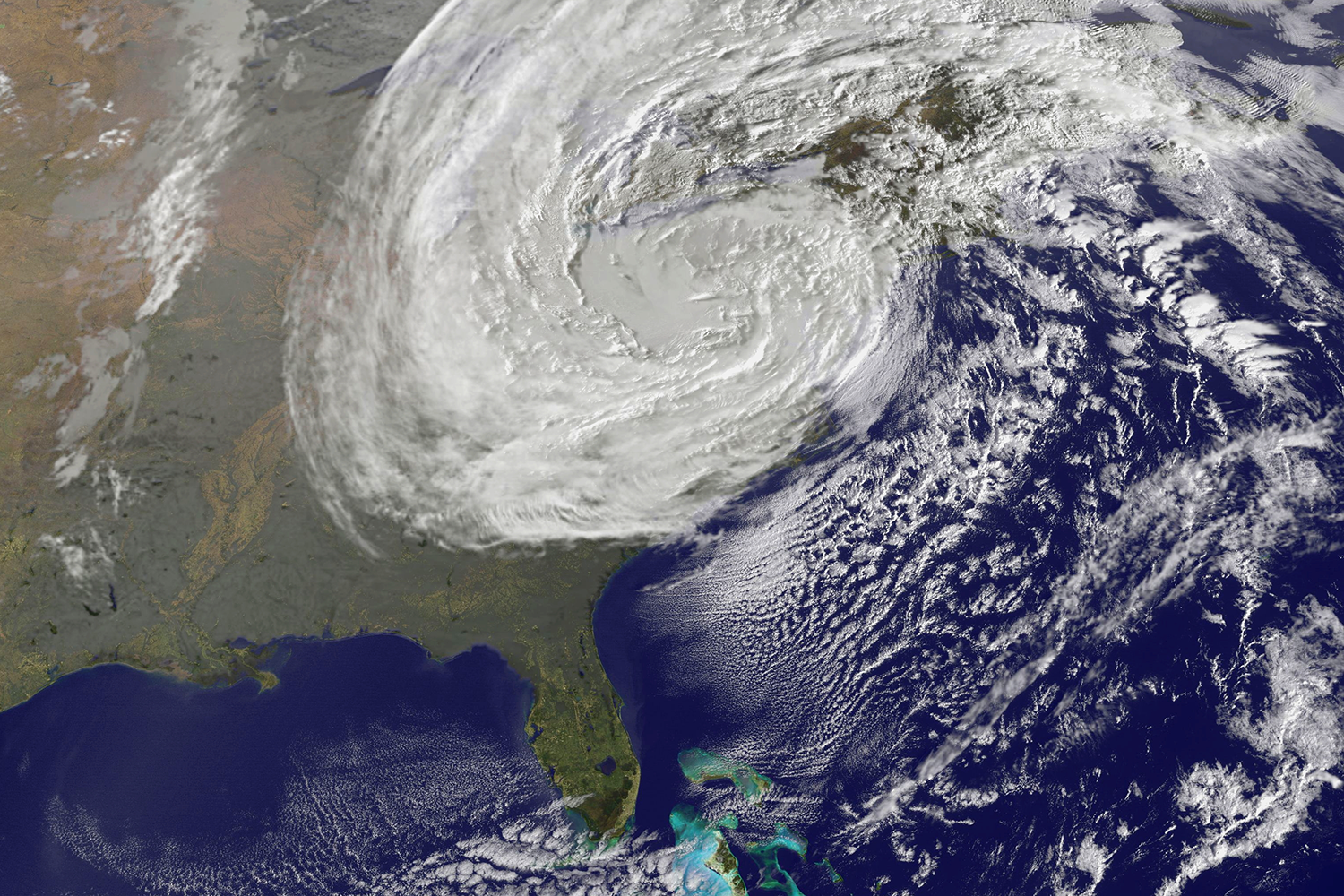

In this working paper, we discuss the challenges of targeting LMI communities affected by Superstorm Sandy in New York State. Since Sandy’s landfall in October 2012, HUD has allocated more than $15 billion in CDBG-DR funds, of which $4.5 billion was granted to New York State. New York City (NYC) received a separate allocation of $4.2 billion, and therefore the state’s recovery efforts are largely, although not exclusively, focused in areas outside of the city. As noted, in the Appropriation Act, Congress gave the HUD secretary the ability to introduce an alternative targeting requirement of not less than 50 percent for all Sandy grantees (U.S. Congress 2013), which the HUD secretary subsequently availed himself of in the initial allocation notice (HUD 2013). As a result, all grantees are subject to the same 50 percent requirement regardless of the underlying demographics of their most-impacted areas. Considering the case of New York State, we ask how effective it is to apply a uniform LMI targeting requirement across the board, with particular focus on infrastructure repair and recovery investments. Further, we ask if there is an empirical approach to setting LMI targets that can more effectively address recovery needs while protecting CDBG’s primary goal of assisting LMI persons and communities.

To empirically assess the impact of this policy with regard to infrastructure investments, we construct hypothetical service areas of various population sizes in New York State, excluding New York City, as well as in New York City as a point of comparison. We estimate the probability of these service areas being documented as LMI in 10,000 rounds of sampling. We use HUD’s income limit data to construct the LMI status of each hypothetical service area and determine whether each service area meets the LMI threshold. We find that New York City and the rest of the state show two distinctly diverging patterns: in New York City, larger service areas are more likely to be documented as LMI. In the rest of the state, on the contrary, as service area sizes increase, there is less likelihood of them being LMI.

Our findings indicate that it may be difficult for New York State to invest in projects that serve large communities, and at the same time count those investments toward the LMI targeting requirement, even when those investments benefit large numbers of LMI persons in absolute terms. This potentially undermines recovery and resiliency investments in the affected areas. We recommend that instead of imposing a one-size-fits-all requirement for all grantees, HUD should consider the socioeconomic conditions of each grantee’s most-impacted areas when establishing the targeting requirements. A more data-driven approach may facilitate disaster-recovery activities in mixed-income areas; it also presents a potential for increasing the threshold even above 70 percent in areas with large concentrations of LMI persons. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

In Section 2 we review the history of CDBG and the LMI national objective. Section 3 provides a brief overview of the recent storms in New York State. In Section 4 we introduce the data and geographic definitions of the affected areas, and outline the general characteristics of New York State. In Section 5 we present an analysis of the probability of a service area within the affected areas being LMI. Section 6 presents some recommendations informed by our empirical findings.