May 2015

Applied learning is the application of previously learned theory whereby students develop skills and knowledge from direct experiences outside a traditional classroom setting. In practice, applied learning includes initiatives from internships and co-ops to civic engagement and service learning.2 It can benefit students by bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and its practical application, increasing self-confidence, and developing critical thinking and career goals.

Applied learning at the State University of New York (SUNY) covers a wide range of experiential learning. SUNY’s own taxonomy refers to three main categories: work-based activities, like co-ops, internships, work study, and clinical placements, under SUNY Works; community-based activities, such as service learning, community service, and civic engagement, under SUNY Serves; and discovery-based activities, like research, entrepreneur- ship, field study, and study abroad, under SUNY Discovers. This report examines work-based initiatives coming under SUNY Works. Even here, the types of work-based experiences differ in nature and structure. In 2012, with support from Lumina Foundation as well as the Carnegie Corporation of New York, SUNY launched “SUNY Works.” The overarching goal of the initiative was to develop a model internship and cooperative education infrastructure to help bring higher education in line with labor market needs. The initiative’s initial objective in 2012 was to use cooperative education to decrease the time to graduation for adult learners.4 Funds from the Carnegie Corporation of New York were earmarked for scale-up of the initiative.

Through new and expanded internships and cooperative learning experiences across eighteen SUNY campuses, SUNY Works aims to increase student retention and degree completion and to improve graduate employment outcomes.5 By providing both paid and unpaid work experiences to students, SUNY Works helps make “academics more relevant by connecting students to work and integrating work experience with curriculum.”6 Paid experiences in particular can also help to offset the financial pressures many students face. Lumina monies were used to assess SUNY Works over the short and medium term. A first evaluation, carried out by the Rockefeller Institute of Government, assessed experiences at nine SUNY campuses, collectively referred to as Phase I pilot sites.

This report found that while Phase I schools were developing model co-op and internship initiatives consistent with the values and commitments of their respective institutions, the success of these campus-level initiatives was contingent on SUNY’s ability to better integrate applied learning into the curriculum and to help increase participation among students, faculty, and employers alike. The report concluded with a recommendation to evaluate the effects of SUNY Works and other forms of applied learning, with a particular focus on student graduation, retention, and em ployment rates. As part of a Carnegie Corporation of New York grant, the present study builds on the earlier report in two ways.

First, this report situates SUNY Works against relevant features of applied learning and strategies used to extend such learning experiences more widely (points of leverage) in other states and systems. We identify those initiative features and points of leverage where the experience has particular relevance for campus-wide, region-wide, or SUNY-wide expansion of SUNY Works. We intentionally focused on the system and campus levels (as opposed to academic program level) because these levels reflect the reach of the vision for applied learning at SUNY. The results of this comparison suggest that, although SUNY Works is unique in the United States (we found no other state or system that has advanced a work-based learning experience initiative on a scale and across the breadth of types of study program and institution encompassed by SUNY Works), we can provide useful comparisons with other initiatives by focusing on components of these endeavors, particularly features of existing initiatives and the points of leverage used to support or bring these initiatives to scale. We generated these features and leverage points through discussions with experts and reference to selected literature.

Second, because the explicit goal of expanding SUNY Works includes an implicit goal of providing worthwhile opportunities for students, we carried out a feasibility study to evaluate the use of administrative data to measure effects of work-based applied learning experiences on one campus in the SUNY system. The pilot study explores the possibility of using campus academic unit records to generate estimates of the effects of internships on reten tion and graduation. The pilot study also explores the use of linked academic-NYS Department of Labor Unemployment Insurance (UI) wage records to generate estimates of the effects of internships on employment outcomes, an information base for analysis of higher education performance now used in many states. For campuses that collect and maintain data on internships, administrative data can uncover effects on retention and graduation. The analysis using wage record information is provided in the supplemental appendix to this report. The report discusses both the opportunities and limitations when it comes to design, measurement, implementation of data transfer and linkages, and analysis and interpretation of results.

These two dimensions are accomplished in a report with four parts. Part I contains a brief description of the approach adopted in this study. In Part II, we identify relevant approaches and experiences elsewhere to help situate applied learning coming under SUNY Works. Part III includes the account of the pilot study of the use of administrative data to estimate the effects of work-based applied learning at one SUNY campus. A short summary with conclusions is presented in Part IV. The report has additional details in the appendices, which can be consulted for more information.

Given study and time constraints, we adopted an approach for the project judged to be most promising. The inquiry followed three strands.

First, to gain a deeper understanding of the history, directions, and decision-making for applied learning on SUNY campuses, we designed a survey instrument to collect information from the pool of campus representatives interested or involved in applied learning. The instrument is provided in Appendix A. Participants attending the September 18-19, 2014, SUNY Applied Learning Workshop in Syracuse, New York, comprised the target population; all participants were invited by Elise Newkirk-Kotfila to complete the survey. Although relatively few participated in the survey, their responses along with information available from other campus-level surveys carried out by SUNY enable a description of features and coverage of learning experiences coming under applied learning initiatives at SUNY campuses.

Second, to uncover relevant experience elsewhere, we engaged both current field experts and contemporary literature. We consulted experts knowledgeable in the field of campus-wide and system initiatives for work-based applied learning, other applied learning, or curriculum development and implementation more generally.8 Project staff participated in three conferences featuring presentations on current initiatives and experiences relevant to this study.

Project staff also conducted a review of extant research, documents, or other materials on approaches to and experiences with applied learning or curriculum change, again at system or campus level. From this examination, we employed a framework developed for this project that identifies key features of applied learning initiatives and the points of leverage which can be used to support or bring about opportunities for students across campuses and the system.10 The features and points of leverage help to situate SUNY Works against experience elsewhere. They also point to approaches in use that might be considered in the development and refinement of strategies in SUNY Works. The examples provided here are generated from the best information available to us, within the timeframe and constraints of the project.

Third, to understand in more detail if it is possible for SUNY or SUNY campuses to use administrative data to evaluate their initiatives we carried out a pilot study of the effects of work-based applied learning. Undertaken with advice from officials at one SUNY campus and the SUNY vice provost for institutional research, the pilot study seeks to evaluate a method for using available campus academic unit records linked to NYS Department of Labor UI wage records to gauge the effects on retention, graduation, and employment rates associated with participation in internships. The pilot allowed for a test of the feasibility of such a method in terms of the analysis and metrics, timeliness, implementation requirements, and usefulness of findings.

SUNY Works promotes work-based learning designed to impart career readiness in students and improve college retention and completion rates. Initially, the aim of the initiative was to facilitate paid, credit-bearing experiences in fields with high employment needs such as science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields.11 As the initiative has continued to grow, however, the emphasis on particular fields and learners has given way to an expansion to all SUNY students. Consistent with the goal of providing opportunities for every student to have an applied learning experience, SUNY Chancellor Nancy Zimpher, alongside a newly comprised task force of business leaders, pledged to engage the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies throughout New York, as well as other large employers, to secure their participation and involvement in the initiative. Already, some of the state’s largest companies including GLOBALFOUNDRIES, General Electric, and IBM have agreed to partner with SUNY schools, alongside local companies like Welch Allyn, Inc., a medical device manufacturer with unique employment needs.

The scope of work-based learning initiatives of SUNY Works has no equivalent. We have not found a counterpart, under state-wide initiative, that envisions broad participation for students across such a range of campuses and fields. Not surprisingly, the work-based applied learning experiences themselves vary. They may be paid or unpaid, credit bearing or noncredit bearing,13 completed during the school year or the summer, with or without faculty supervision.

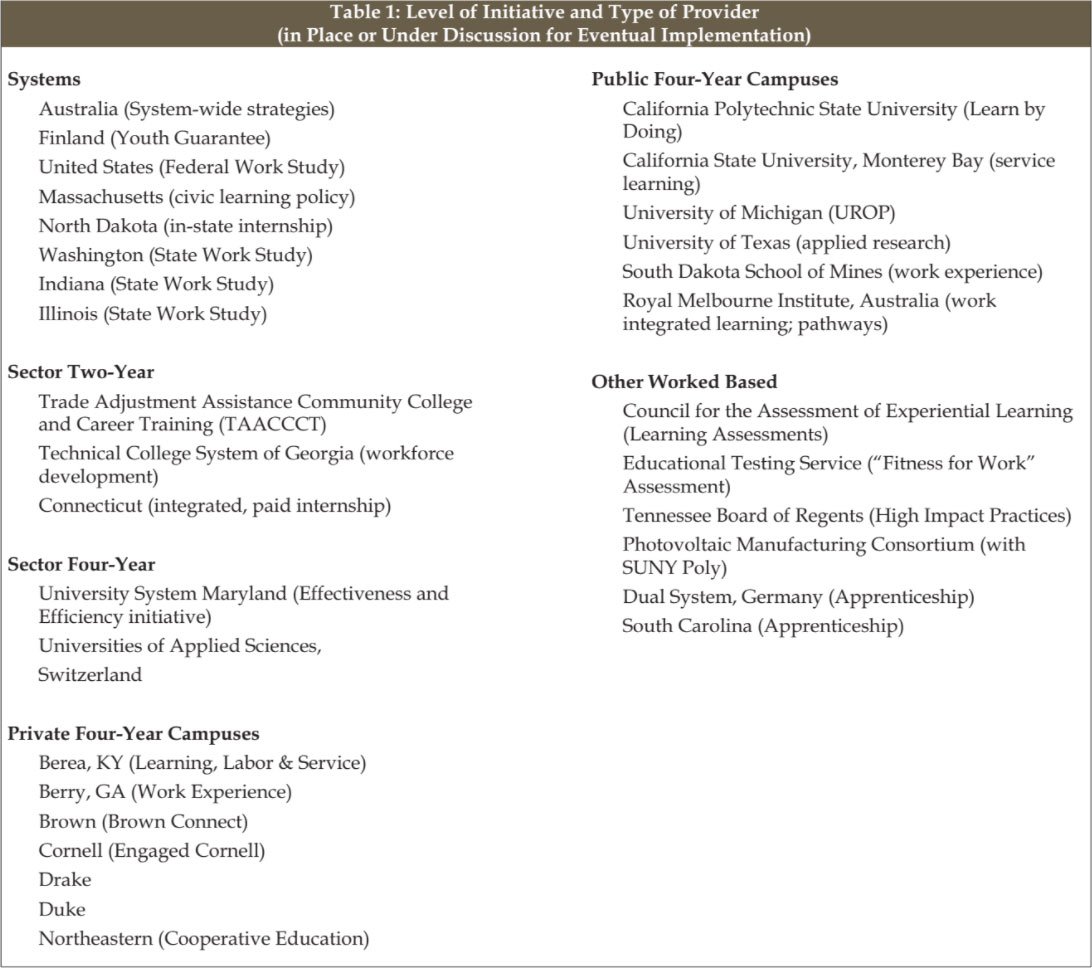

Our approach is to situate SUNY Works against a range of experience elsewhere relevant to SUNY’s goal of extending work-based applied learning opportunities to all students, across fields of study or across campuses. Because SUNY is a sixty-four-campus system that includes community colleges, technical programs, four year colleges, and research universities, our range of institutional initiatives is similarly broad. We look at experiences in systems, like Australia, which recently has sought to extend work-based applied learning in both universities and Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes; community college sector initiatives, like the Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) Grants, which employ external funding to bring about multicampus/multiemployer partnerships for skill training; four-year sector initiatives, like the University System of Maryland, which mandate students to earn 10 percent of credits outside of the classroom, including internships; private four-year campuses like Northeastern, which has well-integrated work-based experiences; and public universities, like the University of Michigan, which through its faculty-led Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program, engage students from all fields in applied learning experiences. In total, we present relevant approaches and experiences of more than two dozen systems, sectors, campuses, and other levels or programs of learning, both domestic and international. We refer to these examples throughout the report. Table 1 lists the initiatives by level (system through campus) and type of provider (e.g., public four-year) that we examined.

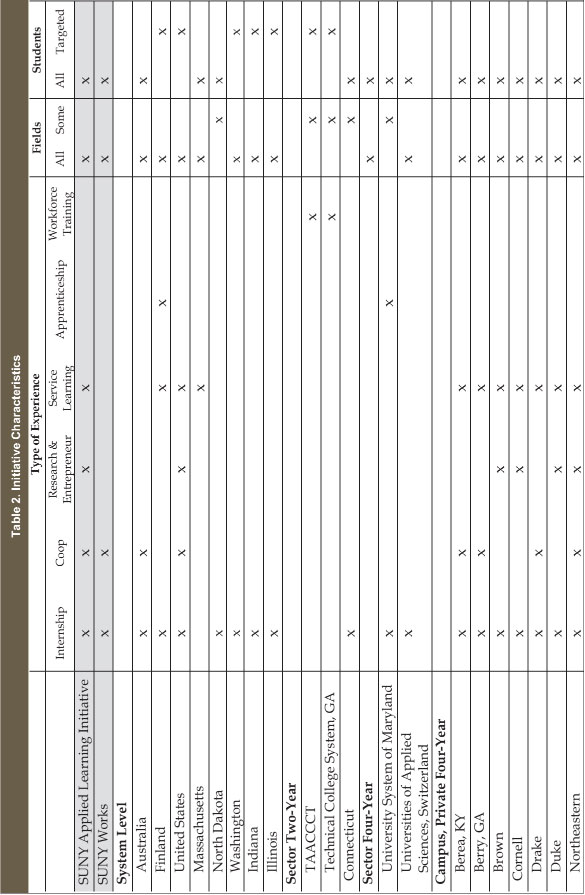

While we illustrate a range of systems, sectors, campuses, and other settings for work-based applied learning, these venues, likewise, offer a variety of applied learning experiences. First, we mapped the initiatives (outlined in Table 1) against type of experience (e.g., internship, coop) and for whom (all fields, targeted) they are offered. Table 2 provides a bird’s eye view of more than two dozen applied learning initiatives identified and examined. It situates SUNY Applied Learning and SUNY Works against these initiatives. Some initiatives, like Australia’s policy on teaching and learning, suggest a good comparison with SUNY Works: both are systems, both are comprised of internships and co-ops, both are not restricted by field or targeted to a particular group of students. Indeed, we offer an extensive description of the relevant Australian strategies. Other initiatives, like University of Michigan’s Undergraduate Research Opportunity program, have key differences from SUNY Works: Urop is research- not work-based. However, the initiative features and scale-up have been innovative and demonstrated results, allowing SUNY the opportunity to draw from the experience lessons applicable to its own work-based applied learning initiatives.

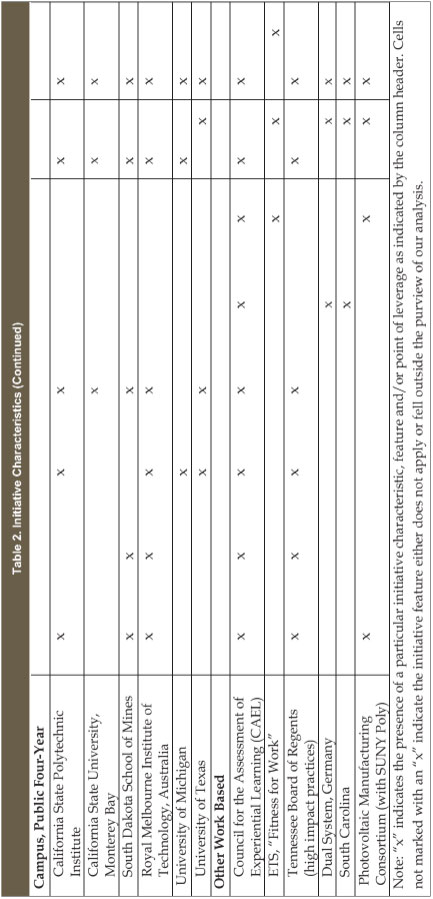

Second, we mapped the initiatives against initiative features that we have identified as “good” or “effective” or “relevant” learning in the literature and among experts.14 Such features include experiences that:

The list here is intended to be illustrative rather than a check list for an ideal type. Successful initiatives, detailed below, use some combination of these key features, often in very different ways. Even limiting the effects of interest to retention, graduation and eventual employment, work-based applied learning experiences coming under SUNY Works are likely to be more effective when they are well-designed; supported by site supervisors and faculty; and assessed in ways that serve student, employer, and academic interests.

Table 3 situates SUNY and SUNY Works with respect to fea- tures that are judged to foster “good” or “effective” or “relevant” learning. Yet SUNY’s applied learning initiatives, in general, and SUNY Works, in particular, are not single system-wide initiatives. Instead, they encompass a collection of practices across a range of campuses. Because SUNY does not mandate particular features and because, even if it did, there would still be variation in what happens in practice, the rows for SUNY and SUNY Works reflect general trends observed at some pilot campuses for some fields of study rather than a strategy SUNY has put in place to foster the implementation of such features system-wide. For example, some Phase I and Phase II schools routinely conduct “workshops” while others do not.

Third, the approaches and experiences reviewed reveal strategies and approaches used to bring about change in learning and teaching, some specifically with reference to applied learning experiences. Although change, whether building on existing provision or introducing new provisions, may naturally follow the interests of those most directly involved — including students, faculty, or employers—systems or campuses, through incentives, information, or mandates may also help to bring it about. For scaling up across a campus and throughout a system, strategies may use points of leverage to engage students, employers, and faculty in work-based applied learning. Summarized in

brief, leverage points include:

With respect to students:

With respect to employers:

With respect to faculty:

We discuss and illustrate many of these leverage points in Part II below. As noted there, a number of these points of leverage already are in place across SUNY. However, information is limited on the number of campuses using any one (or more) of these means and, if used, the present coverage by field or type of student. More generally, the list invites consideration of additional points of leverage that might be well-suited to extend work-based learning experiences more widely, at campus or system levels.

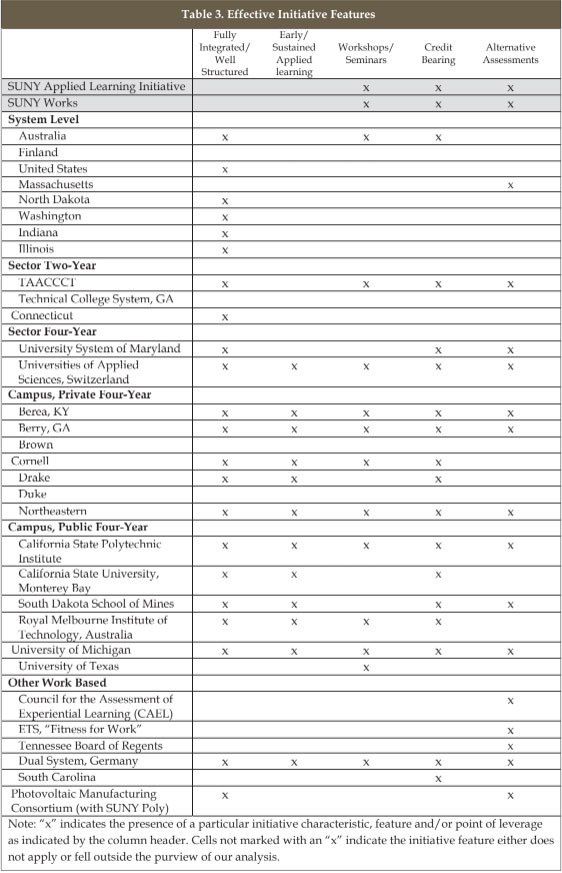

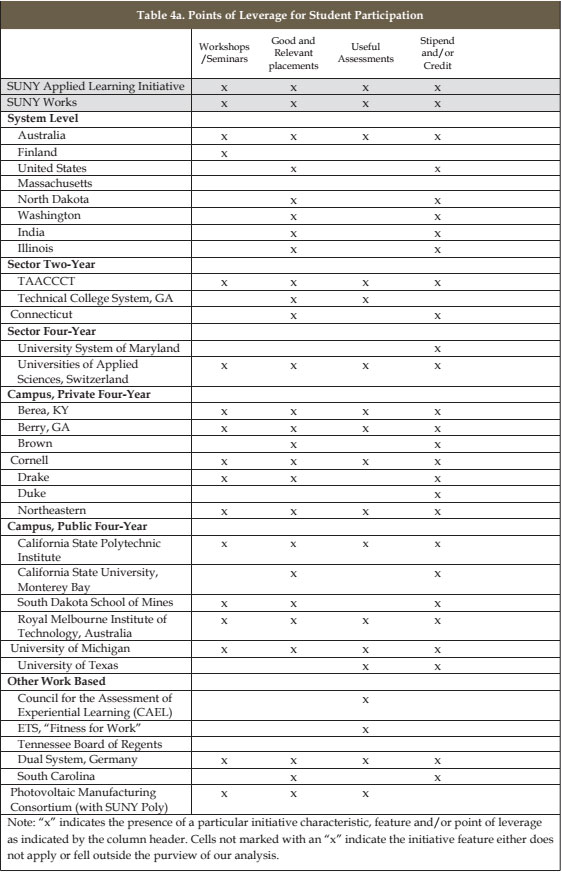

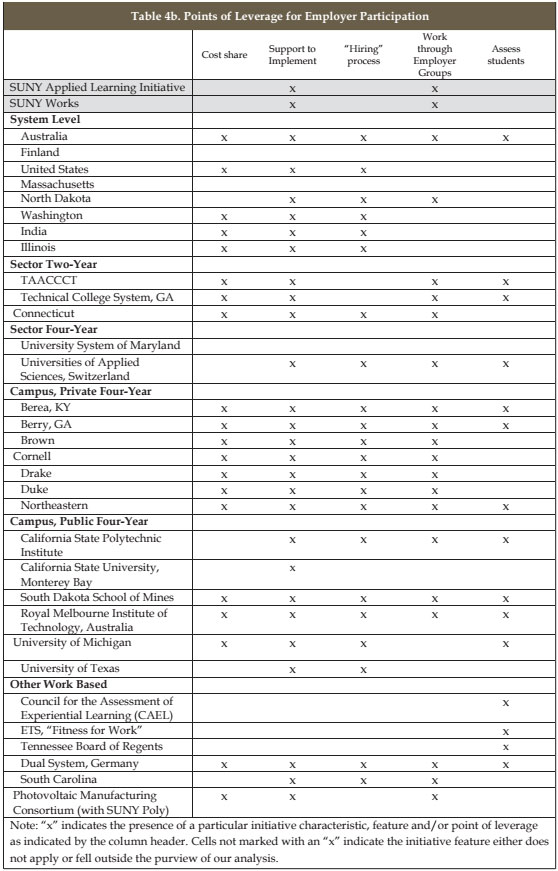

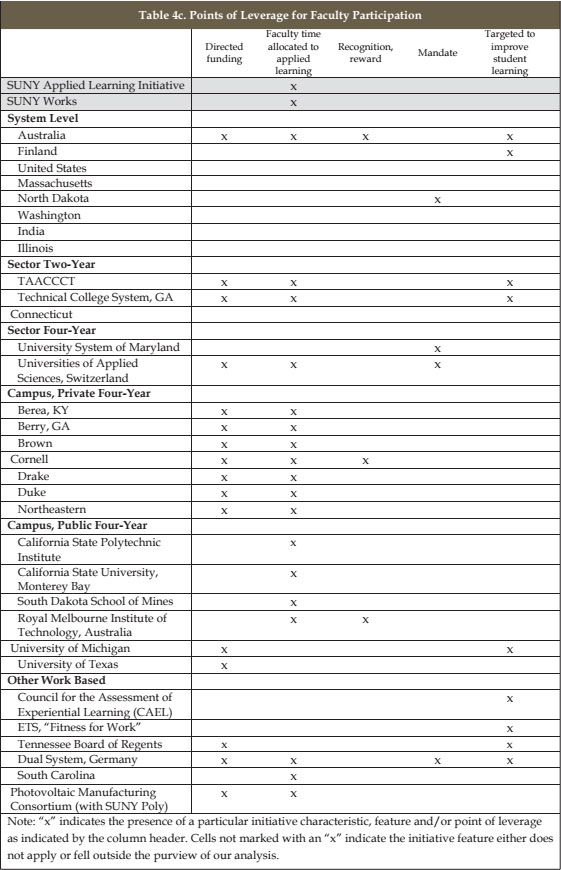

Table 4 locates each identified approach or experience with respect to its points of leverage as they relate to students (4a), employers (4b), and faculty (4c). Again, rows for SUNY and SUNY Works represent trends at the pilot campuses. For example, many pilot campuses have “useful assessments” in place (Table 4a), but some are still struggling to develop measurement tools. Although, for analytical purposes, we separate features and points of leverage, in practice they go hand-in-hand in creating successful initiatives: Worthwhile work-based applied learning experiences are developed, improved, and sustained through support and requirements.

In the next two sections, we describe both key features and leverage points found in five illustrative cases and more than a dozen examples. The cases put the system- or campus-level experiences with work-based applied learning in context. The examples that follow aim primarily to direct attention to concrete means — points of leverage — used to bring about or sustain widely provided opportunities for applied learning at system and campus levels.

While not an exact match to SUNY, the five cases offer important takeaways for SUNY as it seeks to expand workbased applied learning experiences. As mentioned above, Australia’s Commonwealth higher education policy comes closest to a systemic approach that incorporates both universities and technical programs. In addition to Australia, we illustrate Germany’s dual system and Switzerland’s Universities of Applied Sciences, which covers a subset of the levels or sectors coming under SUNY Works. Because SUNY’s approach is often manifested in bottom-up initiatives, we also feature campuswide initiatives: Northeastern University’s coop experience, an initiative built into the fabric of the educational experience, and the University of Michigan’s University Research Opportunity Program (Urop), an initiative built from the ground-up with broad coverage. These five cases are illustrative, but not unique in every respect (we note similar approaches in other settings or campuses).

Higher education systems abroad have struggled with how to encourage work-based learning across institutions that may be very different. The three cases we examine illustrate the different system approaches to targeting and coordinating initiatives. Australia aims to encourage wider use of work-based learning, in part, by using funding and recognition to attract and support faculty involvement in curriculum change. Germany’s Dual System, an apprenticeship approach, builds relationships with employers, encourages employer-education provider partnerships, and provides a pathway to employment for students. The Universities of Applied Sciences in Switzerland, which provides practical training and fully integrated experiences, shows how systems coordinate (at first weakly, then better with more funding) across different establishments.

Australia’s higher education system is comprised of thityseven public and two private full firstdegree institutions that, although autonomous in operations and decisionmaking, come under national control for funding and regulation. Reforms dating to the late 1990s have led to consolidation in the sector, bringing smaller colleges of advanced education into a larger unitary system of universities.16 A separate segment of vocationally oriented institutions of Technical and Further Education (TAFE) provides for shorter posthigh school studies. It is within this broad structure that complementary national initiatives have formed a base for systemlevel extension of workbased applied learning experiences.

Interest in workbased applied learning grew out of evidence of uneven student performance—more than onequarter of students failed to complete their studies—and concerns about the adequacy of a highly educated and wellprepared workforce. The recommendations of the governmentappointed Bradley Review of Higher Education ushered in new conditions for extending “work integrated learning” (the term used in Australia) more widely to institutions and across study programs. The main recommendations — to expand participation in higher education substantially, with additional resources allocated under a dramatic shift to a demandled funding system and performance monitored by a new standards and quality assurance agency (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency) — continue to be rolled out. For the purposes of this report, attention is given to recommendations relevant to workbased applied learning within the broad reforms and to the means adopted within the system in response.

The expansion of participation anticipated in the Bradley Review was understood to extend to students who previously would not have entered higher education, especially students of low socioeconomic status (SES), a target group of longstanding interest in government policy. Partly to address the needs of such new students as well as improve what had been weak performance to date, the Bradley Review stressed student engagement as an essential condition for learning. As part of a broader effort to gather information on teaching, learning, and performance, one of its fortysix recommendations stated: That the Australian Government require all accredited higher education providers to administer the Graduate Destination Survey, Course Experience Questionnaire, and the Australian Survey of Student Engagement from 2009 onwards and report annually on findings.

The recommendation has been partly advanced by the government. It is of particular relevance owing to the concepts of engage ment incorporated in the Australasian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE). Modeled substantially on the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), which is used by a number of US colleges and universities, AUSSE includes an additional engagement scale on work integrated learning. Administered by the Austra lian Council for Educational Research (ACER, similar to the Educational Testing Service), AUSSE was first used in 2007. Through 2012, more than 300 institutional administrations (some duplicates) of AUSSE have been carried out in Australia and New Zealand. As in the Bradley Review, findings with reference to workintegrated learning have been widely cited by higher education institutions and in public policy discussions.

The Department for Education and Training has also made provision for targeted funding for quality improvements in teaching and learning in higher education. Through the Office for Learning and Teaching (and its predecessor), funds are allocated to support projects (with support for collaborative projects), secondments of faculty to the Department for Education and Training, and recognition of exemplary and innovative initiatives (and staff) in the institutions.

Evidence of the wider impact of government strategies can be found in the activities of the nonprofit Australian Collaborative Education Network, (ACEN), the professional association of academic and administrative staff, as well as representatives of employers participating in workintegrated learning. Membership includes institutional, individual, and affiliate memberships.

ACEN provides a venue for sharing experiences with work integrated learning as well as approaches to implement and im prove such experiences. Importantly, membership includes TAFE institutes as well as higher education establishments (and members of their teaching and administrative staffs), indirectly supporting a growth point set out in the Bradley Review to foster new pathways to higher education. Through an annual conference that brings these various parties together, work-integrated learning is given visibility as experiences are shared and made subject to discussion.

ACEN itself has standing. It provides endorsement and indirect non financial support for project proposals under consideration for government or third party funding, under criteria that anticipate application for the wider membership (and beyond). In commentary on National Career Development Strategy Green Paper, for example, ACEN provided support for inclusion of work integrated learning in all study programs, noting also that such inclusion would require resources and incentives.

Points of Leverage:

The “dual system” refers to a form of highly structured, strongly site-based apprenticeship offered in close partnership be- tween education providers and employers. In Germany (and some other continental European countries, most notably Switzerland and Austria), entry into the dual system begins in upper secondary education. About three-fifths of young people enter vocational education at this stage, and of them, nearly three-fourths opt for the dual system. Dual system preparation is offered for well over 300 trades. The dual system is of interest for program features and points of leverage that engage employers and support the delivery of the education and training in partnership.

Apprentices participate in practical training for most of the week, with the contents, duration, and assessments set by guidelines that have been developed and are reviewed by employers and are overseen by the Federal Ministry for Research (which has responsibility for vocational education). Alongside the practical training are classes provided in vocational and education training schools (VET), of about twelve hours per week. Contents cover both general education and instruction specific to the trade, and come under guidelines established by the Conference of State Ministers of Education, the pre-eminent body overseeing education in Germany. More than is common for vocationally oriented education and training at this stage, the dual system provides for an extended period of training and experience under supervision in real work.

Apprentices receive wages, beginning at less than half of what a skilled worker is paid to start. Over the three-to-four-year apprenticeship, apprenticeship wages increase. The structured and anticipated engagement in work and the expenditures obliged under the system accompany strong involvement of employers. Beyond assuming major responsibilities for the design of the apprenticeships within fields (including curricula), employers supervise apprenticeships on site. Consortia formed around trades allow small companies to participate in training, and industry groups provide advice on guidelines. For students entering the dual system, the option is attractive.

Costs are minimal, the education and training are well-structured and involves hands-on, actual work experience, and stipends are paid. The dual system is a path to a good job. Completion of the apprenticeship leads to recognized qualifications that provide for employment in skilled positions in any firm. While skilled workers are more likely to stay with the firms in which they have undertaken training, not all do. For example, Volkswagen’s Chattanooga plant, following the dual system approach in cooperation with the Tennessee Technology Center at Chattanooga State Community College, has found that trained workers are more likely to leave for employment elsewhere than is the case in Germany.

Expenditures are shared. State and local authorities pay for the instruction provided in VET schools, while training firms bear the costs of on-site training. The larger share of expenses is borne by firms in the industries concerned, even taking into account the contribution of apprentices to production. However, some of the firm’s expenses for the dual system might be incurred through company-based training, if the dual system did not exist. Firms generally have been satisfied with the quality of the workforce, and have had a hand in developing an understanding in apprentices of the culture of work in the company. Further, firms use the dual system as means of recruitment, and so avoid costs in that area both for hiring and for replacements of recruits who are ill suited.

The dual system has encountered some difficulties, as companies are less willing to take on apprentices. Some attribute companies’ reluctance to very tight regulations, costs, and education and training that is insufficiently broad enough to enable skilled workers to adapt to evolving needs in the industry.

In Switzerland, as in several continental European countries (Netherlands and Germany, for example), degree studies beyond secondary education are provided in two types of higher education — universities (to which Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology may be included) and universities of applied sciences (UAS).

The UAS came out of a 1990s reform to consolidate, strengthen, and upgrade mostly applied technical and professional programs to accommodate growing demand. The UAS regard themselves as “equivalent but different” than universities. The fields covered in the UAS study programs initially came under national legislation (excepting teacher education). UAS students may come from any prior educational stream (under set admissions guidelines), although a smaller share of students entering UAS programs have followed academic paths through upper secondary school. Provisions are in place for students who have followed a vocational path through and beyond upper secondary education to qualify for entry into either universities or UAS, and a growing number of students coming out of the vocational streams are pursuing both routes.24 About one-third of students in higher education at this level are enrolled in UAS. The Swiss experience under UAS fea- tures the use of practical training and experience fully integrated within the study programs.

In the UAS, students follow well-structured study programs that combine academic coursework with workshops in individual courses. For a bachelor’s program in conservation and restoration, for example, students may participate in regular course modules for the first three days of the week and workshops with instruction in application from professionals for the remainder of the week. During a seventeen-week term, students may spend six weeks in an external practice module, supervised and evaluated by a qualified professional. Two such six-week blocks may be combined into an internship.

Through the UAS reform, more than seventy-five specialized institutions were merged into seven regionally based UAS (five in German-speaking regions, one in French-speaking regions, and one in the Italian-speaking canton).26 The Swiss experience is also of interest in how initiatives with work-based experiences are coordinated across different establishments. Although coming under a single system, each UAS operates differently. Moreover, early experiences showed differences in the efforts made in the early years to establish more co-ordination among the initiatives brought under the oversight of each UAS. Indeed, those UAS that introduced weak co-ordination and centralized management aimed for less ambitious reforms.27 With funding and other supports, co-ordination has increased such that study programs may be offered jointly, affording students work experiences aligned more closely with their interests. In the case of the UAS bachelor’s program in conservation and restoration, for example, four UAS cooperate, offering the same “core” coursework but affording students work experiences that vary by location.

Individual campuses, too, have tried to extend work-based learning opportunities to all students. We provide two cases. Northeastern, which has a strong, well-supported cooperative learning experience, is known for the integration of work and education. This experience, however, is expensive to replicate. The University of Michigan’s Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program is a ground-up faculty initiative to provide research opportunities to undergraduates that has been scaled up. It operates with a more modest infrastructure than Northeastern’s, and benefits from strong faculty and student buy-in (otherwise referred to as a “win-win”).

Northeastern offers study programs oriented toward employment. Among its various applied learning experiences, Northeastern is recognized for co-op learning. The “co-op experience” includes as many as three six-month periods of structured assignments with an employer in the course of a bachelor’s or master’s degree program. Although students are not required to undertake the co-op experience, many do: in 2013-14, 9,823 students were engaged in such experiences, against a total undergraduate enrollment of 17,101 (as of fall 2013). Although a large proportion of students in the co-op experience are in their second or third structured assignment, some 92 percent of students participate in at least one co-op experience and 75 percent do two or more. With respect to its reach across all programs, co-op learning at Northeastern is an illustrative example of scaled up work-based applied learning.

Northeastern’s co-op experience utilizes key initiative features of work-based applied learning. Co-op experiences are well-structured and fully integrated in the curriculum. Learning outcomes associated with experiential learning (i.e., service learning, applied research activities, internships, and co-op learning) are clearly set out, as are templates of the study program with possible sequencing of coursework and co-op experiences. Faculty engagement is extensive and substantive, in the light of the obligation to devise, implement, and refine integrated study programs and the very large share of students who participate in co-op learning.

The first co-op experience begins no earlier than the second semester of the sophomore year. Students may participate in two sixth-month co-op experiences (in a four-year program) or three co-op experiences (for a five-year program). Each student returning from a co-op experience is expected to produce a reflective account of the experience and, in particular, how the experience related to what has been learned in courses. The program allows for different ways to develop that account, e.g., “participating in company seminars, faculty conferences, one-on-one meetings with the co-op coordinator, writing assignments/or presentations.”

Support for students on co-op is provided through the academic advisor and a co-op coordinator, both located in the student’s college. In most colleges, a co-op coordinator teaches a required one-credit course as preparation for the co-op experience, and works with students to help them develop and use job search strategies and techniques, such as securing job referrals and/or references from their own networks, attending job fairs, participating in student information sessions on opportunities, participating in mock interviews, and undertaking research on companies in the field of interest. More than fifty co-op coordinators support students and the academic programs in which they are enrolled, with some colleges having more than one.

The University reports placements with 2,200 employers on six continents.29 For employers, co-op “student-employees” join the staff and work alongside regular employees. Like the job market more generally, employers make the decisions on hiring. Those hired take up structured assignments, and are paid a wage (but not company benefits, e.g., health insurance). The period of the co-op experience, at six months, is long enough to permit the co-op student-employee to “get real work done.” At the same time, employers can evaluate co-op student employees for potential recruitment. The university works with employers, both supporting the process of placement — and eventual potential recruitment — and involving employers in activities to support

co-op arrangements and the study programs in the fields concerned. An employer handbook lays out clearly what is provided by the university (and so not needed by the employer), as well the responsibilities of all parties. The aim is sustained engagement. Employers are welcomed to campus for a variety of activities including student workshops, career fairs, and meetings with staff. In addition, “employers in residence” are provided with an office for single or recurring visits to meet with students regarding career development.

The co-op experience is credited with very strong employment outcomes. The university reports 90 percent of graduates are employed within nine months of graduation, half are employed with their co-op employer, and 85 percent are working in their field of study. For Northeastern, the profile of graduates is strongly oriented toward the professions. For 2012-13, 20.49 percent of bachelor’s degrees were conferred in business; 12.5 percent in health professions; 12.47 percent in engineering, 11.07 percent in construction trades, and 7.6 percent in communications/journalism.

By comparison, social sciences, biology and psychology accounted, respectively, for 11.7, 7.3, and 5.52 percent of bachelor’s graduates in that year. As indicated, students in all fields participate in co-op experiences. Takeaways: Northeastern’s co-ops offer instructive lessons for a scaled up work-based learning initiative on a campus.

Michigan has offered undergraduates the opportunity to participate in faculty-mentored research since 1989. The program originated with faculty in a single department who wanted to encourage and engage under-represented and less prepared students, with the aim of improving retention. Although under-represented students remain a target population (see below), eligibility was broadened to include all students and campus funds support the program. Currently, students from all colleges participate in applied research opportunities and Urop posts 1,300 job opportunities. Urop is an example of a scaled-up applied learning initiative at the campus level. Michigan’s Urop program has ambitions and specificities broadly similar to other campus-wide initiatives elsewhere, such as Brown Connect and Engaged Cornell. Urop utilizes key features of applied learning and benefits from several points of leverage to support and sustain the campus-wide initiative. Those associated with Urop say the applied research experiences are attractive to both faculty and students: It is well-structured to meet the needs of both.

Although submitted on a standard format, the applied research experiences offered by faculty follow no set model as long as activities are appropriately defined and situated within the wider research project of the faculty member. The only expectation is that students have a substantive learning experience. In this way, the student experience is well-structured and, at the same time, aligned with methods and nature of the faculty research project. A key component of Urop is a set of workshops that develop basic research skills. The workshops partly aim to build and reinforce dispositions for structured research activities. They also introduce basic understandings about the process of inquiry/research and how one goes about gathering information and working with it.

Urop gradually has come to rely on students with experience in Urop to “tutor” those entering their first applied research experience. There is a fair amount of peer involvement, even peer control. While not strictly speaking an applied research experience, peer teaching/mentoring requires understanding of what is being taught (and learned) and organizing sessions to convey information and receive feedback. Faculty members appreciate the workshops because the students who work on their projects come with basic knowledge, dispositions, and skills. In that sense, the demands on faculty are reduced. For Urop, the workshops have very modest resource requirements. Students interview for Urop positions. The interviews are taken seriously by both sides, and neither the faculty member nor the Higher Education Applied Work-Based Learning student is assured of a “first choice” in the process. Like job interviews more generally, interviewing for this applied learning initiative means it is possible that a position will go unfilled or a student will not be placed. Urop staff oversees the process, thereby facilitating the matching and helping both students and faculty.

Students apply for Urop positions early in their studies. Students may continue in Urop or other research experiences. Some students continue on with Honors thesis projects while others may participate in faculty research projects outside of Urop. Faculty members have come to value students who begin Urop early, ap preciating that their contributions to faculty research increasewith experience. Less training is needed, and for the student, there is greater potential for recognition in publications (some with secondary authorship) or presentations. Doctoral candidates and post-docs also work with Urop students, gaining experience in return for more intensive one-on-one supervision. In most instances, participation in Urop is credit bearing (see below). Assessments of student performance are based on assignments that vary among projects (from writing an extensive literature review or running an experiment to administering a survey and making a presentation). Urop “alumni” value both the research experience itself and the range of activities and supports provided through Urop, with under-represented students more likely to value each of these aspects than other students.

Urop has a small staff, drawing financial support from the college in which it is formally located (the largest on campus). The program successfully attracted donor support to cover student stipends for a summer program. Some Urop students receive work-study support as well. For these students, Urop assignments may be viewed as more interesting and meaningful than a routine assignment to an office or unit on campus. Work-study students do not receive academic credit for the Urop experience, but they do register for one credit for the workshops and academic supervision of their work. Urop staff handle all of the paperwork, relieving the faculty of the responsibility for reporting requirements. Most Urop projects are located on-campus, but there has been some experience with work-based and service-based learning under the project. Urop has provided community-based research experiences for students working with community organizations that come under a broader university engagement effort in Detroit. The research experiences are supervised by university staff, not staff of the community organization.

Under-represented students and those with weak preparation continue to participate in, and benefit from, Urop. Beyond arrangements for work-study students (who receive support based on financial need) discussed above, Urop attracts community college students to a summer program, increasing the flow of such students to the university and helping with their academic transition. This is a stand-alone program to raise the share of talented low income/under-represented students into leading colleges and Higher Education Applied Work-Based Learning at the State universities who otherwise might not apply.33 This Urop-connected project has been successful: 85 percent of students in the program have enrolled at the university, though there is no alternative with which to compare them. Urop has been the subject of rigorous and varied evaluation to estimate the effects of participation in the research experience. The findings, focusing primarily on under-represented students and those with weak preparation, show that participation in Urop is associated with higher rates of retention, a greater likelihood of entering post-graduate study, and behaviors judged to be more proactive, when compared to an appropriate control group.

Takeways: There are many unique elements of the Urop program. But particular design features make the program successful and are important takeaways for scaling-up initiatives at SUNY.

Although these five cases provide important illustrations of seemingly successful or very recent applied learning initiatives, SUNY initiatives already in place at some campuses manifest some key design features. Stony Brook has launched a co-op initiative that is well structured with clear expectations for students and stakeholders. Stony Brook devised specific evaluation requirements “to avoid potential problems early in the process and to make the initiative successful.”35 They are as follows:

Likewise, several schools have updated and revised their internship manuals to provide clear guidelines as to the structure of initiatives. Monroe Community College, for instance, “updated the employer guide for co-ops and internships making it more professional in appearance”36 while SUNY Orange created separate internship manuals for students and employers. The latter now “includes a section on paid vs. unpaid internships and explains the Department of Labor (DOL) regulations governing unpaid internships.”

Stony Brook, Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), Broome County Community College and Buffalo State include organized workshops or seminars on campus to orient students toward their specific fields of study. Stony Brook developed introductory sessions while scheduling mandatory orientations and co-op information sessions for students.38 These sessions were deemed important by the Career Center because co-op placements had not previously been available on campus. Noting their success, representatives from the Career Center indicated that, “students started paying attention when we initiated information sessions. Students were coming to hear about these opportunities. We would love to expand the program but we just don’t have the resources.”

At FIT, all students seeking an internship must complete one semester of required prep prior to placement. According to Andrew Cronan, director of FIT’s Career and Internship Program, “the prep process is designed to make sure students get professional training

so they represent us and themselves well.”40 Through their involvement with SUNY Works, FIT developed a new set of learning outcomes for the required prep process so that students who complete multiple internships can test out of the requirement. Broome Community College sponsored job readiness activities for students that included weekly, campus-wide student workshops led by local employers and placement specialists. Topics covered included careers in demand, resume writing, interviewing, effective networking, and job searching. To supplement these efforts, various disciplines conducted mock interview days throughout the 2014 spring semester in which employers interviewed students in twenty-minute intervals and completed evaluation sheets. Students were then presented with constructive feedback from these evaluations.41 Through collaboration with Geneseo, Broom has since identified “the need to develop a Professional Skills Preparatory Course.”

Buffalo State designed and is piloting a new Professional Skills Development Module (PSDM). The module consists of a hybrid curriculum, “comprised of four tracks with the overall goal to enhance the quality of the internship experience by equipping students with professional skills before they begin their internship placement. Eight faculty members, from a variety of majors [i.e., psychology, biology, sociology, theater, music, business, fashion and social work], were selected to develop and pilot the modules in their internship classes. Each pilot class will select the workshops/activities/online modules to be completed from among the tracks.”42 Buffalo has also developed a pre- and postsurvey to assess overall student satisfaction and confidence level.

Even though there are benefits from completing internship early, most SUNY students who complete internships do so later in their college career. SUNY may pursue the possibility of fostering opportunities for applied learning experiences earlier in the degree program. Andrew Freeman, director of academic services at Monroe Community College (MCC), summed it up this way: “When you talk about career services and planning upfront, what I was able to uncover was this idea that there’s a lot that MCC offers in a variety of offices but we haven’t done a good job giving a student a laundry list in inspiring them to pursue these opportunities. It’s just been if a student is able to stumble in the right office maybe they get the right information. Collecting what we do, seeing how it flows, and then being able to encourage students in a logical order will bring clarity to things at MCC.”43 Monroe has since developed a Career Action Plan that lists activities a student should engage in to maximize their employability after graduation including internships.

Albany has reported a similar experience. Comments made by the Interim Associate Director of Career Service Noah Simon indicate that prior to implementation of SUNY Works, the Office of Career Services was unaware that many students were completing experiential opportunities in the School of Education (primarily in the domain of field work) as well as in the Study

Abroad program.

Unfortunately, many students remain unaware of opportunities that exist despite campus efforts to reach students through email marketing campaigns, online postings, informational flyers, and promotional videos. For example, Fulton-Montgomery Community College developed two television commercials detailing opportunities for experiential learning on campus. According to a project report submitted to SUNY Central in October 2014, “the marketing and outreach materials allowed our campus to target local residents interested in degree programs that incorporate experiential ‘real world’ learning. Since unemployment rates in the area our campus serves are among the highest in the state, this opportunity to connect residents to programs designed to get them quickly into the workforce was sorely needed and very well received.”

Other campuses, including Onondaga Community College, Stony Brook, and the University at Albany, rely heavily on faculty to encourage students to participate in internships. According to one representative from Career Services at SUNY Albany, “SUNY Works has provided us with a way to engage faculty and other staff in the increasing value of internships and applied learning experiences. Through these conversations we have been able to speak in more classrooms and many faculty and staff have increased conversations and initiatives with students and employers about internship opportunities. These relationships led to an increase of over 17 percent in employers at our annual career fair and an increase of over 25 percent in student attendance at this event.” Broome Community College has developed a good model. Specifically, freshman student orientation sessions feature applied learning presentations by the Career Readiness & Job Placement team in collaboration with the Service Learning and Civic Engagement Coordinators. An information table is also accessible throughout orientation sessions. Marketing campaigns have also been utilized at places like Hudson Valley Community College, Monroe, SUNY Adirondack, and SUNY Orange to develop new relationships with community partners and employers to inform students about the value and availability of co-ops and internships.

Faculty and staff throughout SUNY have expressed concern over the potential for work-based experiences to interfere with degree completion. According to Statewide Co-Op Curriculum Coordinator Bill Ziegler, the question is, “How do you add six months work to that [the curriculum] and still get it done in four years or less?”48 Campuses have responded in a number of ways to promote sustained learning opportunities that are integrated through academic curriculum and help build cumulative knowledge over time. At Stony Brook, for instance, faculty and staff are experimenting with a parallel co-op initiative that differs from Northeastern in that students work part-time while being enrolled full-time. This approach was taken in large part because faculty were “not supportive of the idea of students leaving and working full time for a semester — it breaks the students’ academic sequence and can postpone graduation.”49 Stony Brook has also engaged faculty and administrators to discuss incorporating the co-op initiative into the curriculum of peer education programs.

Ziegler has indicated that curriculum development requires faculty and staff to “think outside the box” when creating internships. “We tried to follow that model where even if you’re an art history major there’s an internship for you. For example, I have an art gallery. We found public space to show student work and I have a student who is the curator.”51 Not surprisingly, some majors prove more difficult to develop internships than others. At Onondaga Community College, for example, Internship Coordinator Rose Martens expressed some difficulty developing internship courses in the humanities.52 By comparison, Onondaga established three new courses in the Interior Design program to give students more flexibility when seeking internship credit. Students may choose from courses that are one, two and three credits and require sixty, 120, and 108 hours, respectively.53 New internships were also established for the new Nuclear Technology program.

While every SUNY Works pilot campus offers credit-bearing internships, the number of students completing noncredit bearing internships is unknown. That being said, some schools are adopting new policies designed to designate courses with an experiential component. For example, Cayuga Community College developed an EL Designation Policy which allows faculty to designate their courses as EL on course descriptions and transcripts.54 This policy took two years to put in place and required feedback and buy-in from the faculty association.

Finally, successful initiatives offer alternative assessment. Although this occurs within SUNY, it does not appear to be very common. FIT recently developed a Transfer of Credit Policy for academic internships. This policy allows students who complete an academically equivalent internship within or outside of SUNY to transfer those credits to FIT. Despite the relatively low-cost of implementation, FIT anticipates “this will not be a highly used option for students” because FIT’s “internship program is valued and desirable for students.” SUNY also has an expert in prior learning assessment. Nan Travers currently serves as the director of the Office of Collegewide Academic Review at Empire State College. Her work focuses mainly, “on the policies and practices of self-designed student degree programs and the assessment of prior college-level learning.”56 As founding co-editor of PLA Inside Out: An International Journal on the Theory, Research, and Practice in Prior Learning Assessment, Travers’ knowledge and expertise lend themselves to future growth in this area. Nonetheless, widespread implementation of PLA’s remains uncommon throughout most of SUNY.

Universities and colleges perceive a great benefit in providing applied work-based experiences for their students. As Michael True, Washington Internship Institute board member, explains:

Colleges helping students find internships is a growing trend. Schools raising money to fund unpaid internships is a growing trend. Use of alumni in this way is a growing trend. All of this is on the upswing because it all makes it that much easier for students to transition to the workplace….

If applied learning offers benefits, how can opportunities be expanded or brought to scale? The answer, we suggest, can be found in key points of leverage to promote and expand applied learning opportunities. Points of leverage are ways to extend good or effective applied learning experiences, at system or campus levels. Although there is scant research testing these points of leverage, we draw on expert advice and examples of relevant approaches adopted at system or campus levels (beyond the five illustrative cases outlined above). We group the points of leverage under three major types: requirements, incentives, and buy-in. Situating points of leverage advanced by other systems and universities against policies, strategies, and experiences in SUNY Works, shows potential areas for policy development in SUNY Works.

Systems have expanded applied learning initiatives by mandating or requiring participation of students and faculty. The University System of Maryland requires students to earn credits outside the classroom, including credits earned in internships. The Youth Guarantee in Finland goes much farther in supporting opportunities for work, including a guarantee that anyone under twenty-five will be offered employment if they are job seekers. Massachusetts’ new “Civic Learning” policy is a directed, if broadly based, mandate that obliges all students in the system to acquire “applied competencies that citizens need” without reference to how students should acquire those competencies.

Rather than require student or faculty participation, systems can encourage it, most often through increased funding. Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) grants, for example, encourage partnerships between campuses and employers by providing funds. Similar initiatives can be found, with state funds, within the Technical College System of Georgia and, with respect to targeted and grounded research, at the University of Texas.

Individual campuses have also incentivized greater participation, again through increased funding opportunities. Brown University launched BrownConnect, which develops and lists internships and other applied learning experiences. It also provides stipends for students who participate. Similarly, Cornell launched its own initiative, Engaged Cornell, to encourage community engagement. Cornell anticipates $150 million over ten years to support community partnerships, curriculum change, and faculty development.

Systems may also encourage greater participation in work-based applied learning through federal and state policy development. Indiana and Illinois have created new work-study funds to support internships, including in the private sector. Systems have worked with state and regional governing bodies to promote funding or tax concessions for employers who make a commitment to create or promote jobs — a strategy that might be purposefully extended to include internships.

Campuses, likewise, encourage buy-in from employers. Experience with strategies and approaches elsewhere suggest that employer engagement is facilitated through arrangements that reduce administrative and other demands while affording benefits. Beyond those already identified in the illustrative cases, targeted approaches include working with employer consortia for workforce training, for example, the Photovoltaic Manufacturing Consortium.

Campuses can encourage faculty buy-in by growing and promoting internal initiatives, as in the University of Michigan’s Urop program (discussed above). Campus initiatives may encourage students to take internships and to complete work-based projects as part of their curriculum, like California State Polytechnic Institute (Cal Poly). Strong work-based initiatives may encourage students to participate simply because they get results. The South Dakota School of Mines, for example, has well-paid work-based opportunities with many different employers. Work is integrated as a value in the university. Drake and Duke, in less directed ways, provide opportunities that attract students to applied learning (including work-based applied learning).

Over time, work can become a core part of the education at a particular campus. These schools are able to get faculty and student buy-in through recruitment: individuals may choose them because of their work-based emphasis. Northeastern, described above, is known for its co-op experience. Liberal arts schools, like Berry College and Berea College, integrate work fully into their curriculum and educational experience. California State University, Monterey Bay (CSUMB), provides support for service learning, a requirement for all students integral to the CSUMB mission. The Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) has emphasized work since its origins. Unlike Northeastern, Berry, or Berea, the RMIT incorporates technical programs as well as traditional bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorates.

Although assessments are not a tool to expand opportunities, they are a means to identify and expand good opportunities. Simply measuring work-based experience (as in Australia) brings greater attention to the issue in policy debates. Tennessee uses funding directed to campuses, offering grants to support academic program development that incorporate research-backed “high impact practices,” including applied learning.75 Because work-based learning across different campuses and initiatives has different goals, there is not necessarily a single standard for assessment. In fact, students and employers both may appreciate the value and use of alternative forms of assessment, which identify and refer to knowledge, skills, and attitudes not typically assessed in on-campus coursework. The Educational Testing Service is examining noncognitive qualities to judge the “fit” between a student and a potential employment opportunity. The Council for Assessment of Experiential Learning offers assessments based not only on tests but also review of portfolios and other means. More assessments, and more sophisticated assessments, have the potential to allow systems and campuses to provide better experiences for students and a better fit for employers.

The examples of points of leverage just described suggest a broad range of strategies to extend and support work-based applied learning experiences. Some of these strategies SUNY has already adopted, others it has not. For starters, SUNY may be moving toward making applied learning a requirement for degree completion. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo wants to make experiential learning a requirement for SUNY students, a sentiment echoed in Chancellor Zimpher’s 2015 State of the University address: “every SUNY degree will include an applied learning or internship opportunity as a prerequisite to graduation.”78 The challenge, then, is to identify and provide the kinds of supports and leverage that might best encourage expansion of such experiences. In terms of incentives for students, the vast majority of placements throughout SUNY Works pilot campuses remain unpaid.

Nonetheless, some schools have attempted to expand the total number of paid internships through their involvement with SUNY Works. Most notably, FIT used funds from Lumina Foundation to create nine $1,000 summer internships. These opportunities were directed specifically at students unable to complete internships due to economic hardships. FIT is currently working with its development team to find grants to continue this program beyond the SUNY Works initiative.

With respect to employer buy-in, most Phase I and Phase II campuses are developing initiatives largely at the department level. At Brockport, Buffalo, Canton, Cortland, Erie, Niagara, and Stony Brook, for example, partners are identified by faculty, students, and career offices. Institutional outreach efforts such as career fairs (Albany) and alumni connections (Binghamton and Cornell) are also utilized. Contributing to these efforts, Chancellor Nancy Zimpher recently announced a plan to engage the CEOs of every Fortune 500 company with a presence in New York, as well as other large employers, to help promote the expansion of SUNY Works. Consistent with Governor Cuomo’s START-UP NY economic development plan, the chancellor is also working to “establish a Co-Op Task Force comprised of business leaders from across the state with a focus on regional Chambers of Commerce and companies coming to New York.”Although, to the best of our knowledge, SUNY has not leveraged work-study programs or state-funding, it has developed assessment tools. Building assessment into expansion, to see what works and therefore what ought to be furthered, is an important part of scaling up. A vast majority of Phase I and Phase II schools have developed a wide range of assessment tools to monitor student performance and learning outcomes. These typically include employer satisfaction surveys, reflective journal entries, and final papers. At Onondaga Community College, for example, employers are asked to rate each student’s work-related skills (i.e., industry skills, organizational skills and work ethic) on a scale of one to five with one being the lowest performing indicator and five being the highest. Similarly, Stony Brook asks employers to rate each student’s workplace etiquette, communication skills, and job performance on a scale of one to five with one being unacceptable and five being exceptional. Several schools have also developed assessments to monitor the overall quality of placements. At FIT, for example, students evaluate the worksite experience as well as the curriculum. With respect to the former, students are presented with questions like:

With respect to the latter, students are asked whether classroom instruction helped them to assess their own personal skills, talents, values and interests, identify career possibilities, and write effective resumes.85 Despite the prevalence of student and employer satisfaction surveys and other forms of assessment, these practices vary from campus to campus.

Although there are many points of leverage that can be engaged to scale initiatives up, as we have mentioned in this report, it is crucial to understand what initiatives are effective to make good decisions about what should be scaled up. There are many ways to define effective: increasing student satisfaction, better assessments of student qualification for jobs, or better academic outcomes, to name a few. In the following section we report on a pilot study undertaken to evaluate the use of administrative data to estimate the effects of work-based applied learning. In particular, we look at whether work-based learning experience has an effect on student retention, graduation, and employment at a single SUNY campus.

Campuses participating in Phase I of Lumina-supported SUNY Works initiative had little or weak evidence of the effects of student participation in work-based applied learning on retention, graduation and eventually employment outcomes.86 The problem is a general one: campuses and their academic program units have only in recent years mounted more systematic and ongoing efforts to track student progress to graduation. Further, curriculum options (such as applied learning) tend to be examined in one-off studies. Until fairly recently with the emergence of digital records and reporting and internet-based survey options, campuses and systems have not routinely and systematically tracked graduates into the postgraduate period. Under these circumstances, the use of extant administrative information to track students and graduates, with more finely grained analyses of differences in progress, completion, and employment according to curriculum options such as work-based applied learning, opens up potentially useful information that can be obtained easily, quickly, and routinely. Recognizing both the lack of information and the potential, the Baseline Report included a recommendation to undertake an exploratory study to test the feasibility of using extant academic unit records, also linked to NYS Department of Labor UI wage records, to estimate such effects. Under the present project, we have carried forward this recommendation.

There are several advantages of an exploratory study. First, the design of the study obliges attention to methods and measures, and so can surface needed details on applied learning experiences that are not presently collected. Second, the design developed for the pilot serves as a method that might be adopted for use at campus and system level. Third, the pilot provides a first test of the use of information on graduates employed in New York State. Although not new in a number of states, the possibilities for linking SUNY academic unit records with NYS Department of Labor UI wage records opened up only this year. SUNY has undertaken a few studies using linked UI wage record information, and this pilot study has relied on SUNY’s vice president for institutional research to pursue the linked data.

The pilot study aims to estimate the effects of participation in work-based applied learning at one SUNY campus, which was selected because of existing data resources. The Rockefeller Institute project team worked closely with two campus officials with very close knowledge of the types of applied learning experiences offered in particular degree programs and also with expertise and familiarity working with academic unit records and linked UI wage records. The project also secured advice from an expert with experience working with linked academic unit record-wage record data in other states as well as experts in the design of assessment of learning studies.

Researchers have used academic unit records to understand the effects of work-based experience on academic results, such as grades, credits earned, and retention to the second year. While research using linked academic — wage record data bases has grown over recent years, these studies are more particular, examining differences by campus for degrees in a certain field and a particular levels. This pilot study, by contrast, is distinctive in its aim to apply linked unit record data to estimate the more finely- grained academic and employment effects of work-based applied learning within and across degree programs. For this reason, the considerations in the design, metrics, and implementation are presented in some detail along with the difficulties arising. The difficulties stand as important limitations. Given that academic unit records typically lack details on curriculum options such as applied learning experiences, substantive involvement of knowledgeable campus-level staff will be required to carry out such analyses in the near term.

The pilot sought to explore how far — and how — student unit records can be used to both track academic results and employment outcomes (the latter through matches with the NYSDOL UI wage records). The pilot had as its purpose to explore the feasibility of such an approach, to lay out the kinds of metrics that could be used, and to identify limitations and gaps. What is learned from a pilot advanced at campus level should reveal the potential — and limitations — of the approach for other campuses and SUNY Works.

Isolating the impact of work-oriented learning experiences: The pilot study was conceived as a method to gauge the effects of work-oriented applied learning experiences on retention, graduation, and employment outcomes. To estimate effects, the academic and employment outcomes of participants in such experiences need to be compared to the outcomes of students who did not participate. Since the students in these two groups may differ in ways other than participation in work-based applied learning experiences, the method used ideally should take into account the extent to which other attributes are associated with retention, graduation, and employment outcomes. With expert advice, we considered different options. The most appropriate for the pilot study is a “matched” students strategy. Under this approach, academic and socioeconomic information is used to “match” students, i.e., to identify students who we judge to have the same propensity to participate in a work-based applied learning experience. The academic and employment outcomes for those who participated in the applied learning experience are compared to those in the “matched” group of students to come up with an estimate of the effects. Several relevant

Higher Education Applied Work-Based Learning at the State University of New York studies have used such a method to come up with estimates of the effects of applied learning. Working with the participating SUNY campus, we explored the information available on the academic unit records and the UI wage records. For the analysis (and, subsequently, interpretation of results), several considerations and limitations were identified. Work-based learning opportunities differ in structure and requirement, which presents challenges for overall assessment of impact.

The intended outcomes of participation in SUNY Works is increased retention, graduation, and employment. The academic unit records alone and linked to UI wage records are well-suited to examine these outcomes, but they are not perfect. The Rockefeller Institute project team consulted with experts and reviewed extant studies on the types and range of measures to be constructed. Although we employed academic unit records from a single campus to generate estimates of the effects of work-based applied learning experiences on retention, graduation and employment outcomes, additional measures may better capture the complexity of academic pathways, student experiences, and wide range of potential effects.

While the UI wage records linked to academic unit records are an important way to measure employment (through wages) in New York State, here, too, there are considerations and limitations.

Work with academic unit records, and in particular linking these records to NYSDOL wage records, required a sequence of steps. The main considerations, as well as a key limitation, are identified here.

We use descriptive data, bivariate analyses, and multivariate regressions (more specifically, a series of logistic regressions) to reveal the relationships between participation in an internship and the demographic, socioeconomic, and academic backgrounds of students, and learning outcomes, including retention, graduation, and labor market outcomes.

As mentioned above, associations do not always reveal causal relationships: Even if participation in an internship is associated with a higher probability of retention, graduation, employment, and earnings, the associations may mask other causes for favorable outcomes. Among statistical approaches used to capture the effects of participation in internships, propensity score matching (PSM) is a method that has been applied with respect to work-based or discovery experiences.101 The PSM approach takes two steps to identify the causal effects of interest. First, available observable attributes are used to calculate the propensity to participate in a treatment, which, in our analyses, is participation in the internship. An individual who took an internship is matched to another who did not take the internship (in the control group) but had the same “propensity” to take the internship based on other attributes. This step is an approximation to a randomizedcontrolled trial (RCT). It addresses the problem of extrapolation that often exists in ordinary least square (OLS) regressions102 and guarantees that apples are only compared to apples. Second, the difference in outcomes between the treatments and controls — internship/no internship for each matched pair (or matched group) is calculated and then averaged among the matched pairs (matched groups) to get an estimate of the difference in the learning or labor market outcome of interest. However, the causal estimates using PSM are only valid to the extent that we capture the most important observable attributes of students. Available information on relevant attributes, such as parents’ education, family income, and so forth, is limited. Moreover, we do not have measures of important, but unobservable attributes, such as motivations.

These limitations raise a second area where further information will be needed to make full and appropriate use of such methods in the future (the first being program details on internships). Even with additional information, attention will need to be directed to group sizes sufficient to permit finely grained analyses under PSM. Put simply, interest in generating estimates of the effects of internships by feature and field for use at campus level directs attention to smaller groups while appropriately implemented PSM techniques require larger numbers. Strategies, such as those adopted for the project to draw from several years’ cohorts, will need to be identified and evaluated. A further consideration is identification of the appropriate comparison groups. For estimation of the effects of internship on retention, full analyses are limited to the sub-sample of students retained to the prior year. For estimation of the effects of internship on graduation, full analyses are limited to the sub-sample of students retained to Spring semester of year four (for year four graduation).103 For estimation of the effects of internships on employment outcomes, analyses are limited to the sub-population of graduates.

Academic records do not capture all internship experiences. Just over 17 percent (or 1,435 out of the 8,348) of entering students took at least one internship by the beginning of the Fall term of their seventh academic year, or the Fall term of the seventh year, at the participating campus. As mentioned, this number is roughly half of the 35 percent of college graduates that Gallup reports.104 However, Gallup counts all self-reported internships, while the academic records that we are working with capture only those internships that are credited within study programs. Students who took advantage of internships most often completed them late in their academic career. The most common time to take an internship was the Spring and Fall terms of the third and fourth academic years (see Appendix C, Table 3.3 and Figure 3.1).

Females, African Americans, those whose tuition residency in first term was not foreign, and those with relatively lower SAT scores (both math and critical reading) were more likely to participate in at least one internship during their studies at the participating SUNY campus.