In the recent report, Giving or Getting? New York’s Balance of Payments with the Federal Government, Rockefeller Institute evaluated how all fifty states compared in the tax revenue they sent to the federal government (receipts) and the levels of spending they received from the federal government (expenditures). Forty states had a positive balance of payments; they received more money from Washington than they sent. In our last blog post we looked at “the givers.” These states have high income levels and, as a result, pay more in payroll taxes than other states. These high tax burdens were not offset by high levels of federal spending, leading to negative balances of payments. In this post we take a closer look at the winners, the states with high balances of payments. Our analysis finds there are two categories of getters: states with large federal workforces and states with low incomes.

Table 1 shows the ten states with the highest per capita balance of payments. The ratio of expenditures to receipts tells us how much each state receives in federal spending for each dollar it sends in taxes. For every $1 Virginians pay in taxes, the residents receive twice as much in federal spending.

Table 1. Balance of Payments: The Getters

| Per Capita BOP (in $s) | Federal Spending per $1 | |

| Virginia | $10,301 | 1.97 |

| Kentucky | $9,145 | 2.35 |

| New Mexico | $8,692 | 2.34 |

| West Virginia | $7,283 | 2.17 |

| Alaska | $7,048 | 1.67 |

| Mississippi | $6,880 | 2.19 |

| Alabama | $6,694 | 1.99 |

| Maryland | $6,035 | 1.53 |

| Maine | $5,572 | 1.74 |

| Hawaii | $ 5,270 | 1.61 |

Combined, these ten states account for 9.4 percent of all taxes to the federal government, but receive 14.9 percent of federal expenditures. They receive $1.92 for every dollar they send in taxes. The national per capita balance of payments is $1,925, which means that on average, states receive $1.20 in federal spending for every tax dollar.

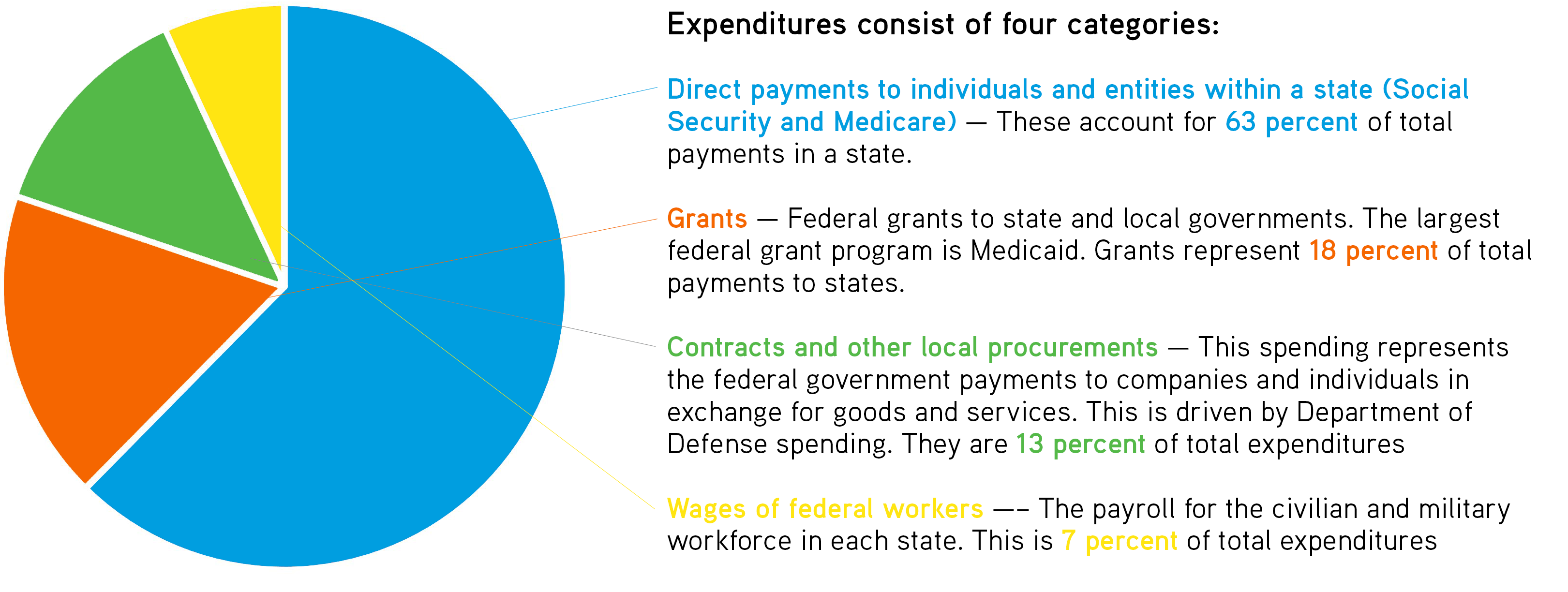

The balance of payments calculation is made up of two categories: receipts and expenditures. We have included how each of the states ranks in total expenditures received and receipts paid. The ten biggest winners all rank very highly in expenditures received per capita, which is why they are winners.

However, there are two different groups of states when it comes to receipts: (1) “High expenditure, high receipts” are states that, while they get a lot of money from the federal government, they also rank very high in taxes paid to the federal government (Virginia, Alaska, Maryland, and Hawaii). These are high-income states with high tax burdens. (2) “High expenditure, low receipts” are states with low tax burdens (Kentucky, New Mexico, West Virginia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Maine). We will take a look at these two categories to see what drives their taxes and expenditures.

High Expenditure, High Receipts: The Federal Workforce (Virginia, Maryland, Alaska, and Hawaii)

Combined, these four states account for 13 percent of the total federal workforce. This means a lot of contract and wage spending flows into these states. Virginia received $9,044 per person in federal contracts in 2017 and Maryland ranked second with $4,958. Both states receive considerably more than the national average of $1,780. Federal wages in Hawaii were $3,776 per person and $3,230 in Alaska. Virginia and Maryland ranked third and fourth in federal wages, earning $2,739 and $2,616 annually.

These states earn higher wages and generate higher-than-average tax revenues, but also receive high levels of federal spending. The spending well outpaces the revenues sent to the federal government and the result is a high positive balance of payments.

High Expenditure, Low Receipts: The Low Income States (Kentucky, New Mexico, West Virginia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Maine)

Low-income states benefit through two channels. Lower average income means a smaller tax burden. The lower incomes, higher poverty levels, and older populations of these states also mean higher levels of payments to individuals through social programs. These states get a larger allocation of Social Security, government and military retirement pensions, Medicare and Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and housing assistance.

Table 2 shows that the average resident of Kentucky pays $2,780 less in federal taxes and receives $4,440 more in federal payments, driven by direct payments, grants, and several defense contracts. The lower tax and higher payments result in a per capita balance of payments of $9,145, or $7,219 more than the national average. New Mexico also has a low tax burden and higher-than-average spending on federal payroll, leading to the third highest balance of payments.

The low balance of payments in West Virginia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Maine are primarily driven by the lower relative tax burden compared to higher-than-average spending. While they do have higher-than-average expenditures, they do not have large installations of federal employees or a cluster of federal contractors. Their balance of payments are the result of their low income.

Table 2. Difference from the National Average (Low-Income States)

| Tax Receipts to Federal Government | Federal Expenditures to State | Balance of Payments | |

| National Average | $9,532 | $11,457 | $1,925 |

| Difference from US Average: | |||

| Kentucky | -$2,780 | $4,440 | $7,219 |

| New Mexico | -$3,057 | $3,710 | $6,766 |

| West Virginia | -$3,293 | $2,065 | $5,358 |

| Mississippi | -$3,760 | $1,195 | $4,955 |

| Alabama | -$2,737 | $2,031 | $4,768 |

| Maine | -$2,050 | $1,596 | $3,646 |

Conclusion

Two factors create winners in the Federal Balance of Payments calculations. The first is the presence of a large federal workforce. Having a large federal presence means that the state will receive a larger allotment of federal payroll dollars and the corresponding federal contracts. The higher levels of federal expenditures in states such as Virginia and Maryland offset higher tax burdens and results in a large and positive balance of payments. The second factor that drives a positive balance of payments is average income in the state. Low-income states will pay less in federal income taxes, driving balance of payments down. In addition, residents of these states are more likely to receive federal support through Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, or SNAP. These states pay less and receive higher-than-average expenditures, resulting in a high balance of payments.

The result is that the taxes paid by high-income states in the Northeast offset the lower tax contributions and higher spending in lower-income states in the Southeast.

Laura Schultz is director of fiscal analysis and senior economist at the Rockefeller Institute of Government