As we observe National Gun Violence Awareness Month, it is crucial to shed light on intimate partner homicide (IPH), fatal incidents where a person is killed by a current or former intimate partner. These incidents are different from other homicides in terms of their causes and effects, which are far-reaching even though they comprise a relatively small percentage of homicides overall. Women are disproportionately the victims of IPH, with the majority (77.9 percent) of IPHs committed by men against women. In heterosexual relationships, most female victims of IPH are killed by men who abused them and most male victims of IPH are killed by women that they abused.

IPHs generally follow a pattern of abuse escalation and there are often warning signs before the killing, making them one of the most preventable types of homicides. These incidents are seldom random acts of violence. In this blog, I explore the paramount importance of IPH prevention, delve into its trends, and outline strategies to combat this public health concern. My hope is that this blog sheds light on IPH and provides a knowledge base for those who are interested in learning more about this type of violence.

From 2015 to 2019, official law enforcement statistics suggest that there were approximately 5,200 people killed by an intimate partner. These numbers may have increased since 2019, as the Centers for Disease Control’s WISQARS reports an increase in femicide, but it is impossible to ascertain an exact figure on motive and, therefore, if the cases were IPHs due to changes in how the FBI collects crime data. Since the FBI started collecting homicide data in 1976, firearm injuries have consistently been the most frequent cause of death in IPH cases, and firearm IPH increased 26 percent from 2010 to 2019. Firearm ownership and threats with a firearm before a fatal event have consistently been shown to be one of the most robust risk factors for IPH.

The presence of a firearm in a home where there is a history of IPV increases the odds of an IPH by over 400 percent.

The bulk of what is known about the risks for IPH stems from the seminal study on femicide risk conducted by Campbell and colleagues in the late 1990s. The researchers collected data from police records of homicides and survivors of nonlethal intimate partner violence (IPV). In total, 19 risk factors were identified, with the most salient ones being an increase in the frequency or severity of violence, perpetrator gun ownership, recent separation, perpetrator unemployment, past use or threats with a weapon, and threats to kill. This seminal study found that IPH is not a random act of violence, but rather more typically a culmination of a pattern of abuse, coercion, and control, which is exacerbated by the presence of a firearm. Indeed, the presence of a firearm in a home where there is a history of IPV increases the odds of an IPH by over 400 percent.

Disproportionate Harm

As indicated above, while IPH can impact victims of all sexes, females are disproportionately affected. Statistics show that of all femicides around 40–50 percent are killed by a current or former intimate partner, in contrast to only 5–8 percent of male homicide victims that are killed by a current or former partner. IPV often precedes IPH, and violence against a female partner is one of the main precursors to IPH, regardless of the victim’s sex. Approximately two-thirds to three-quarters of female IPH victims were abused by their partners before being killed. When females kill male partners, there has been prior IPV against them in approximately 75 percent percent of cases. Perpetrators of IPH often use violence as a means to assert power and control over their female partners, which some posit is a reflection of broader societal gender inequality, hegemonic masculinity, and misogyny.

Statistics show that of all femicides around 40–50 percent are killed by a current or former intimate partner, in contrast to only 5–8 percent of male homicide victims that are killed by a current or former partner.

Moreover, children are often the secondary victims of IPH. Almost half of the victims in multiple homicide incidents involving IPH are children, and many victims of IPH are parents. Children are also likely to witness IPV prior to the homicide, the homicide itself, or find the body of their parent in the aftermath. Youth who survive the IPH of a parent may experience emotional/cognitive distortions, guilt, and shame. This experience could, in turn, lead to adverse life outcomes, such as poor performance in school and a history of anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Additionally, the normalization of violence in the home during their formative years may also perpetuate a cycle of abuse and victimization that extends into their adult lives.

What Can Be Done?

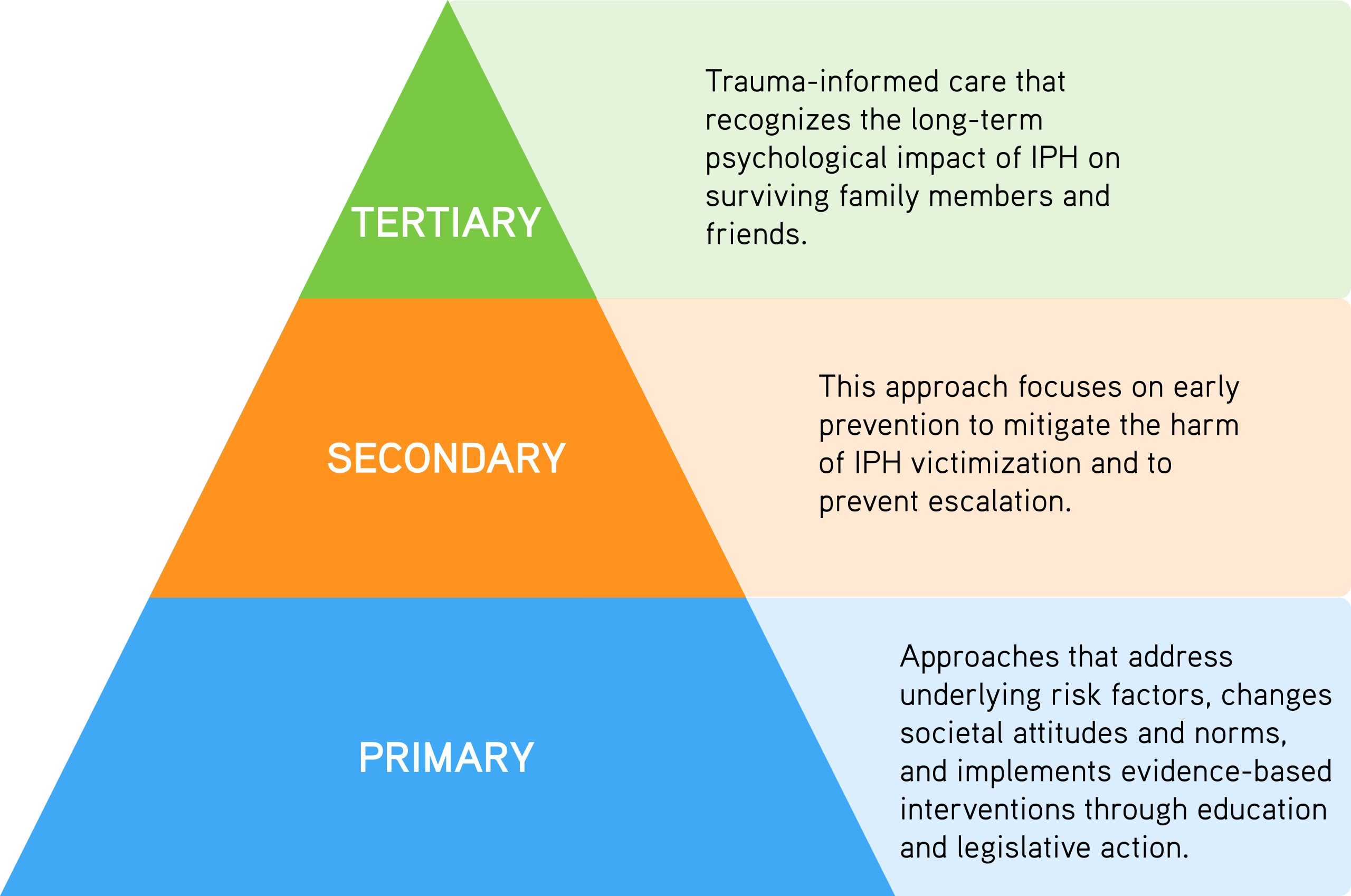

Given that IPV is a common precursor to IPH and that the bulk of incidents are committed with a firearm, there are multiple potential intervention points before the IPH. The intervention can be grouped into primary, secondary, or tertiary efforts. Primary prevention strategies address such incidents by intervening before any violence occurs. Secondary prevention focuses on at-risk populations and sets forth interventions to mitigate the harm caused by IPV victimization and prevent escalation. Finally, tertiary prevention strategies focus on responding to the aftermath of IPH, supporting survivors, and facilitating their recovery.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention of IPH requires a multifaceted approach that addresses underlying risk factors, changes societal attitudes and norms, and implements evidence-based interventions through education and legislative action. Since IPH is usually preceded by IPV, education and awareness-raising campaigns aimed at changing societal attitudes and norms surrounding domestic violence are important prevention measures. This involves dispelling myths about gender roles and promoting healthy relationship dynamics. Through education, teachers and community stakeholders can empower individuals to recognize warning signs and seek help to prevent violence.

Given the prevalence of firearm use in the commission of IPH, effective primary prevention also requires robust legislative measures to regulate firearm access and ownership and prevent irresponsible and illegal gun ownership. Policies such as universal background checks, firearm restraining orders, and safe storage laws can prevent abusers from obtaining firearms and reduce the likelihood of lethal violence. Strengthening enforcement mechanisms by having systems in place to ensure individuals convicted of abuse dispose of their guns and closing loopholes that allow “boyfriends” (those who aren’t married to, living with, or don’t have a child with a partner) to be exempt in existing laws restricting access are critical steps in enhancing the effectiveness of legislative interventions.

Secondary Prevention

While primary prevention strategies aim to stop IPV before it occurs, secondary prevention focuses on early intervention to mitigate the harm and prevent escalation. A critical aspect of secondary prevention is the early identification of individuals at risk of IPH victimization and perpetration. Healthcare providers, law enforcement agencies, and social service organizations can implement screening protocols to identify at-risk individuals. Providing immediate crisis intervention and support services to survivors, such as access to emergency shelter, counseling, legal advocacy, and financial assistance, can help victims get out of abusive relationships before it is too late. Crisis hotlines and support groups can also offer survivors a lifeline during times of crisis, connecting them with resources and helping them navigate the complexities of leaving abusive relationships. Abusive partners may also be referred to programs that help folks perpetrating IPV cease their harmful behaviors. In cases where firearms are present in IPV situations, domestic violence restraining orders (DVROs) and extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs) could be used as tools to prevent the use of a firearm to continue the abuse and its escalation. To that end, more legal advocacy organizations could offer and improve services to survivors to facilitate representation in court proceedings, assistance with obtaining restraining orders, and support navigating the criminal justice system.

Tertiary Prevention

Central to tertiary prevention is the provision of trauma-informed care, which is vital to efforts at any level of prevention, that recognizes the profound psychological impact of IPH on surviving family members and friends. Counseling, therapy, and support groups can help survivors cope with trauma and develop resilience as they navigate their healing and recovery process. Monetary aid can also facilitate healing as families navigate funeral arrangements and starting over after the loss of their loved one. Legal advocacy organizations can also provide survivors with representation in court proceedings and support in navigating the complexities of the legal system.

IPH Intervention Pyramid

SOURCE: UC Santa Barbara Campus Advocacy, Resources & Education.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, as we reflect on National Gun Violence Awareness Month, let us not forget the importance of addressing IPH. The stark reality is that IPH is not just a statistic—it is a tragedy with far-reaching consequences for individuals, families, and communities. Thousands of lives are lost to this form of violence each year. And firearms play a significant role in the perpetration of IPH, increasing the risk of lethality and exacerbating the trauma experienced by IPV survivors. Preventing IPH requires a multifaceted approach encompassing primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention efforts. By implementing evidence-based interventions to provide preventative education, early identification, trauma-informed resources, and by limiting the access of firearms by known abusers, we can create safer, more resilient communities where individuals can thrive free from the threat of IPV and IPH.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jesenia Pizarro is a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Criminology and Criminal Justice and the Office of Gender-Based Violence. Her work primarily focuses on homicide, and she is the editor-in-chief of Homicide Studies and an affiliate scholar with the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium.