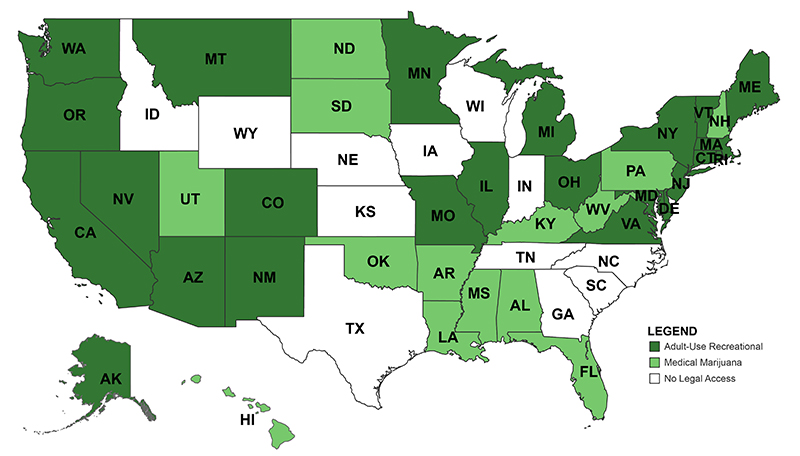

Momentum is growing to change federal policies on cannabis. Public opinion has shifted substantially since the 1970’s War on Drugs and as the states have steadily eased legal access to cannabis. As of this year, 38 states and the District of Columbia (DC) have adopted comprehensive medical marijuana programs and 24 states and DC have adopted adult-use recreational programs (see map below). Our new book with NYU Press, Green Rush: The Rise of Medical Marijuana in the United States, makes the argument that the states are not only reflective of broader federal changes, but central to the story of cannabis policy reform. In this blog, we expand on that argument to consider not only what will change as the federal effort to reclassify cannabis as a Schedule III drug moves forward (public comment on the proposed rule ended on July 20, receiving over 40,000 comments), but also the great many things that will stay the same under this less restrictive status.

Legal Access to Cannabis Across the United States

Some Things Change

Since the passage of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (CSA), cannabis has been federally designated as a Schedule I drug. This means that, according to federal law, the plant has no medicinal value and is highly prone to abuse. Other Schedule I drugs include heroin, LSD, and ecstasy. Almost immediately after the passage of the CSA, this status was questioned. President Nixon’s own Shafer Commission, which was created under the CSA to study marijuana’s scheduling, recommended that marijuana be decriminalized. Conservative intellectual William F. Buckley, through his publication National Review, supported the Commission’s conclusions at the time and called for legalization. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) was also founded in 1970, and both the new organization and others toured the states pushing for reform. But it has taken over 50 years for significant federal reform to occur.

In 2022, President Biden ordered the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Attorney General to begin a scheduling review for marijuana. This is one of several methods for initiating scheduling or rescheduling a controlled substance. After a scientific and medical review, in August 2023, HHS recommended to the Department of Justice (DOJ) that marijuana be moved to Schedule III. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), within the DOJ, has regulatory authority over (re)scheduling and ultimately accepted HHS’s recommendation by issuing a proposed rule on May 21, 2024, that would move marijuana to Schedule III. The full rulemaking process following a proposal could take months to years, depending on how it unfolds, including resolution of potential litigation. At the close of the comment period on July 20, DEA had received nearly 43,000 comments, the vast majority of which appear to support either re- or de-scheduling marijuana. However, the agency must review and consider these comments when issuing the final rule. Moving to Schedule III will mean that under federal law cannabis is considered to have a “moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence” and that it has medicinal value. Schedule III drugs, like Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, and testosterone, can be prescribed by doctors, if they are approved by the FDA.

So, what changes with respect to cannabis once it is on Schedule III? And importantly, what changes for the states that have legalized access to the plant in some way for their residents? We categorize the major changes into two buckets: business and research.

Moving to Schedule III will mean that under federal law cannabis is considered to have a “moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence” and that it has medicinal value.

Moving to Schedule III will help resolve significant barriers for cannabis businesses. Two prominent business challenges that came with cannabis’s Schedule I status were limits on banking and a prohibition from tax credits. Banking and credit union services are governed by the federal government in the United States, and transactions related to Schedule I controlled substances, like cannabis, are subject to federal money laundering laws. As with DOJ enforcement, banking regulators have engaged in some forbearance on prosecuting state-legal cannabis businesses and the banks and credit unions that serve them, but without rescheduling this forbearance is ephemeral, as we have written about previously. This kind of forbearance on federal enforcement has also largely been at the discretion of presidential administrations and their appointees and is, therefore, subject to changes in administrations.

Moving cannabis to Schedule III will allow the industry to have direct access to banking services, which should reduce reliance on cash and give business owners and license seekers access to loans. Additionally, cannabis businesses will be able to deduct their expenses just like any other business when paying federal taxes. Examples of expenses that cannot currently be deducted by cannabis businesses include rent, legal fees, marketing costs, license fees, and cleaning services, in addition to others. Currently, businesses are prohibited from doing so because Section 280E of the federal tax code disallows businesses that traffic in controlled substances on Schedules I and II from taking these deductions.

Additionally, high-quality research on the medical efficacy of cannabis has been remarkably difficult due to its listing as a Schedule I substance. There have been criticisms over the years about the process of legally doing cannabis research, as well as the quality of the product from the nation’s only federally legal grower at the University of Mississippi. A nearly 500-page report issued in 2017 by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) that examined the full body of evidence on the health effects of cannabis reported that:

There are specific regulatory barriers, including the classification of cannabis as a Schedule I substance, that impede the advancement of cannabis and cannabinoid research. It is often difficult for researchers to gain access to the quantity, quality, and type of cannabis product necessary to address specific research questions on the health effects of cannabis use.

Moreover, federal research dollars, which have largely driven the medical research agenda, have been disproportionately awarded for research on the harms of cannabis, not its potential medical benefits, skewing the availability of research with respect to (re)scheduling.

States have led the way in developing cannabis clinical research programs—recognizing the need for good science both for effective regulation, as well as to address concerns and arguments against rescheduling and legalization that point to the lack of available evidence. But the move to Schedule III will reduce the federal barriers to further cannabis research, including that which could lead to FDA-approved cannabis medications. For example, it is much easier to register to conduct research on substances under Schedule III and it is also easier to conduct randomized controlled trials that offer far better insights into efficacy, dosage, side effects, and more, in comparison to the observational studies of cannabis users that have been relied upon.

More Things Stay the Same

The relationship between research and FDA approval is a good place to consider what will not change in the face of rescheduling. Not all research barriers are gone. Registration is still required for research using Schedule III substances, but it is not as laborious as Schedule I. Researchers will still face the restriction of using only federal suppliers for their cannabis, meaning they will still not be able to research the actual products used by many Americans in states where there is legal consumption. Clinical trials using cannabis would become easier, though there are already backlogs in the FDA approving cannabis trials under its investigational new drug application process. Moreover, the way people use cannabis therapeutically is very different than typical pharmaceuticals. Namely, they use the plant itself, which has hundreds of compounds, rather than isolated compounds that can be consistently and perfectly duplicated in a lab. While new cannabis-derived drugs with FDA approval could one day be prescribed by doctors, this does not apply to the many thousands of medical (not to mention recreational) strains of cannabis and products currently on the market in state-legal programs.

Cannabis as a medicine more broadly will require a different regulatory approach. Even the FDA has recognized that cannabis is a fundamentally different product than pharmaceuticals or supplements. It has already punted to Congress the topic of regulating CBD products, asking for new authority to do so rather than using rules related to supplements. The key issue is that the cannabis plant has hundreds of cannabinoids. They can work in isolation, but there are also significant cooperative effects with different cannabinoids and terpenes, which means scientists have to get the correct combination of cannabinoids to achieve efficacy for treating different medical conditions. Understanding the therapeutic potential of these compounds is really in its scientific infancy. That is why reducing barriers to medical cannabis research through rescheduling may be even more significant than the relief rescheduling will provide to businesses.

Even the FDA has recognized that cannabis is a fundamentally different product than pharmaceuticals or supplements. It has already punted to Congress the topic of regulating CBD products, asking for new authority to do so rather than using rules related to supplements.

The recent stumble in the effort to bring MDMA (aka ecstasy) to market for treating post-traumatic stress disorder, which centered on questions about clinical trials, illustrates the stakes of having high-quality available scientific research.

This research may take decades more to conduct in the case of cannabis. This means that even with rescheduling, states are likely to remain the central innovators on related drug policy in the United States. States are the ones figuring out how to balance industry goals while maintaining patient and consumer safety. They are the ones wrestling with trying to end the illicit and gray markets for cannabis, while also trying to capitalize on the promises of revenues from cannabis taxes. States are grappling with how to right the wrongs from the 50-year drug war with social equity programs that aim to reinvest cannabis revenue into the communities most harmed. And states will continue addressing policy questions related to cannabis that we cannot even anticipate in the short- and long-term. The history of drug policy in the United States cannot be well told without considering state actions. Moreover, the current moment, even at the federal level, cannot be understood without them.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Daniel J. Mallinson is a Richard P. Nathan Policy fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government and an associate professor of public policy and administration and professor-in-charge of the masters in public administration program in the School of Public Affairs at Penn State Harrisburg (PSH).

Lee Hannah is a professor of political science at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.