This week there will be a potential showdown between Republicans and Democrats in the United States Senate over the confirmation of Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court. Senate Democrats, opposed over the nominee’s ideology, are pushing to filibuster Judge Gorsuch’s nomination. The filibuster is the unique Senate procedure that allows for continued debate and delay of a confirmation vote unless there are 60 votes to close the debate. The Democrats claim they have enough votes to prevent the 60-vote motion for cloture. If that is the case, the Republicans are claiming they will invoke the “nuclear option” where they will change the Senate rules, allowing the confirmation to proceed with a simple majority and eliminating the threat of filibuster.

Who emerges victorious from this showdown remains to be seen, but such an effort reminds me of the examination of failed Supreme Court confirmations in John Massaro’s engrossing book, Supremely Political: The Role of Ideology and Presidential Management in Unsuccessful Supreme Court Nominations.[2]

As Massaro notes “…the Senate’s action in refusing to confirm some future Supreme Court nominee will be, as it has always been, supremely political.” The question is: are all the ingredients present to defeat the Gorsuch nomination? Although we don’t have a crystal ball to see how this will end, Massaro found there are a combination of several factors needed to defeat a Supreme Court nominee.

1. Political Ideology

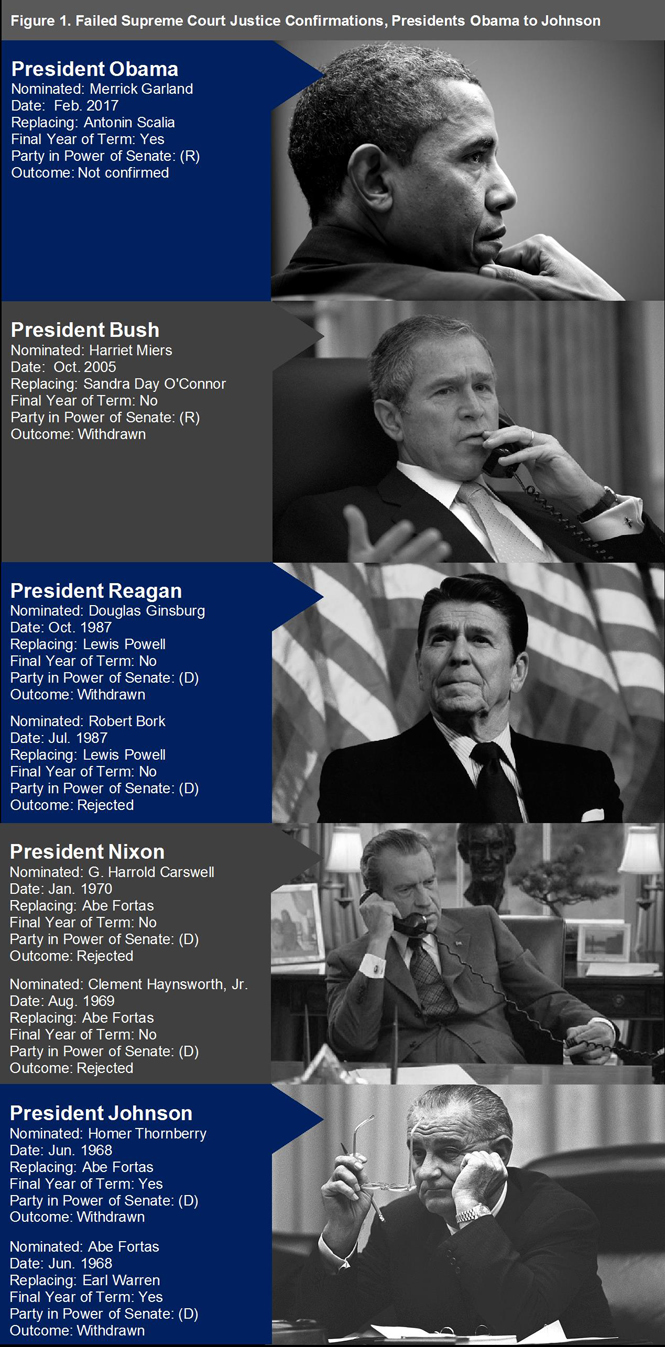

Confirmations have failed when the president’s party was in the minority in the Senate coupled with significant ideological differences. This was the case when President Ronald Reagan nominated Robert H. Bork (rejected by the Senate) and Douglas Ginsburg (withdrawn). Both were considered by the Democrats to be too extreme. In the case of Judge Gorsuch, the Senate majority is of the same party as the president. Party identification isn’t always the perfect proxy for political ideology. In one of the more recent cases, George W. Bush’s unsuccessful attempt to confirm Harriet Miers was opposed largely from the conservative elements of the Republican party while in control of the Senate. This is not the case, however, for Neil Gorsuch. The Republican party is largely unified behind his confirmation.

Failed nominees are often ideologically more polarizing than the justice they are potentially replacing. President Reagan’s nominations of Judge Bork and Ginsburg (both considered ideologically very conservative — or “extreme,” according to Senate Democrats) to replace the centrist swing vote of Lewis Powell was one of the central issues behind the defeat of both nominees. In the end, President Reagan was able to get the Senate to confirm a more centrist candidate, Anthony Kennedy. In the case of the current nomination, Neil Gorsuch, considered to be very conservative, would be replacing Antonin Scalia, regarded as one of the Supreme Court’s most conservative justices. Unless Gorsuch is deemed not conservative enough, concerns about the cumulative ideological shift of the Court would be unlikely to be a factor in confirmation.

2. Timing: Lame Duck Status

Along with ideological differences of the majority party in the Senate, individuals nominated in the last year of a president’s term also face a higher rate of failure. President Lyndon Johnson’s nomination of Justice Abe Fortas to replace Chief Justice Earl Warren and President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland were both made in the last year of a president’s term. Again, this is not the case for Neil Gorsuch.

3. Presidential (Mis)management

In other unsuccessful Supreme Court nominations, presidential (mis)management played a role. Selecting nominees that are vulnerable on nonideological or nonpartisan grounds increases the chance of failure. The nominations of both Abe Fortas and Clement F. Haynsworth, Jr., were plagued with ethical concerns that helped doom their confirmations. Strategic blunders in failing to cultivate relationships with senators can also inhibit the chance of a successful nomination. Relying on the judgement of only a few senators, not adequately assessing the mood of the Senate, engaging in limited consultation with senators, prolonging the process, and alienating many members during the process were all critical errors presidents have made during the confirmation process. Although politically contentious, there aren’t similar presidential management issues at play in Judge Gorsuch’s confirmation process.

Moreover, close personal relationships between the nominee and the president can also be problematic. For example, President Johnson and Abe Fortas were close personal friends, and President George W. Bush’s nominee Harriet Miers had previously served as his personal lawyer and White House counsel. This was a major reason why both nominees ultimately were withdrawn. Again, this isn’t a factor with Judge Gorsuch, who has no known pre-existing connection to President Trump

Like past confirmations, the Gorsuch nomination is controversial. But, unlike these other cases, Gorsuch is not more ideologically extreme than the justice he is replacing, is not being nominated in the last year of the president’s term, and does not have the same types of ethical concerns. Moreover, the president’s political party is in the majority in the Senate. Thus, the current factors don’t appear to be enough to stop the ultimate confirmation of Judge Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. However, given the emerging fight over the role of the filibuster in the Supreme Court confirmation process — and whether the nuclear option is used — may change not only the course of Judge Gorsuch’s path, but may also have a profound effect on future confirmations. Time will tell.

[1] I want to thank Deputy Director for Research Patricia Strach and Chief of Staff Heather Trela for their thoughtful comments.

[2] John Massaro, Supremely Political: The Role of Ideology and Presidential Management in Unsuccessful Supreme Court Nominations (Albany: SUNY Press, 1990): 197.