Buried under the headline news of the day is the continuing story of transparency in government, including the movement to open the government’s data. The latest thread in this story is taking place in the United States Congress where the fate of the recently reintroduced Open, Public, Electronic and Necessary (OPEN) Government Data Act is under consideration, with minimal attention from the press. The goal of this bill is to make data from federal agencies freely and publicly available to anyone, in a variety of user-friendly formats. A topic that may seem irrelevant to most Americans’ daily lives, unleashing government data to the public, possesses a largely untapped transformative power with implications for government, industry, and society. If passed, the bill might help improve government operations, spur innovation in the private sector, and improve the well-being of ordinary citizens.

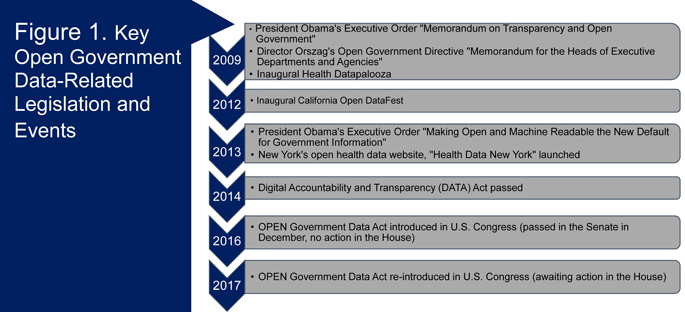

This bill is not a new concept. One of President Barack Obama’s first actions as president was a Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government, which catalyzed future activities, including a directive on open government that required federal agencies to publish downloadable data in open formats that are “platform independent, machine readable, and made available to the public without restrictions that would impede the reuse of that information.”[1] The Congress later enacted the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA) of 2014, which required agencies to publish government spending information in open formats.

The Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government’s requirements to publish data that can be discovered, accessed, and used — combined with rapid advances in information and communication technologies — cultivated an “open data revolution.” Civic hackers, government staff, researchers, community groups, corporations, and others now come together to use data in novel ways to produce public value. For example, the Health Datapalooza annual meeting started in 2009 as a small group of developers and other data enthusiasts participating in a Community Health Data Initiative and has since expanded to over 1,600 attendees from the public, private, nonprofit, and academic sectors, with expertise in healthcare and technology. Some state and local governments are also running events to cultivate these communities, including Chicago’s weekly hackathons (“Chi Hack Night”) and annual Open Data Day events, the annual California HHS Open DataFest, and the New York State Health Innovation Challenge.

To codify President Obama’s executive orders, the Open, Public, Electronic and Necessary (OPEN) Government Data Act was introduced in both the House and the Senate in April 2016. The Senate passed the bill in December 2016. But the House took no action on the bill in 2016, and it was reintroduced in March of 2017. The bill aims to make data from federal agencies available in an open format and with an open license for use. Data that are protected by law, such as personally identifiable information, would still be maintained in secure facilities. However, data that can be disseminated legally would be published as machine-readable, with open formats that do not require specialized software to access, at no cost, and without restrictions on use.

The OPEN Government Data Act would not require substantial changes in federal agencies’ routine activities related to data publication. For example, it does not require the production of new data or change in the Data.gov infrastructure that already exists. About 50 federal agencies, along with state governments, municipalities, and other entities, have already contributed over 160,000 downloadable datasets.[2] The bill’s unique contribution is that it codifies the 2013 open government data executive order into a routine activity and specifies how to open government data. The bill requires public institutions to post datasets to Data.gov and designate a point of contact; it creates a federal chief information officer position; and it removes administrative barriers to publishing data that have already undergone careful scrutiny to ensure they meet security and confidentiality standards.

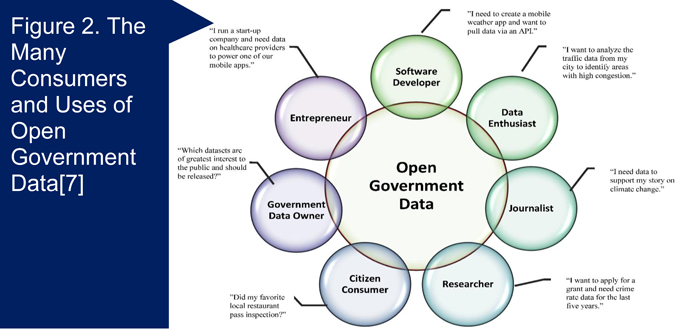

President Obama’s 2013 open data executive order framed open data as part of a broader initiative to improve government transparency and citizen engagement. However, when speaking with federal, state, and municipal staff responsible for publishing open data and other open data thought leaders across the country, we have found that these benefits are only the tip of the iceberg.[3] Specifically, open data are critical to an emerging open data ecosystem, in which users repurpose data and repackage them for other users, creating applications and improving the data. By making government data more discoverable, accessible, and usable, new data consumers with different skills and ideas can create innovations that government agencies do not have the time or capacity to accomplish in-house. Some early examples are:

- Linking San Francisco’s food safety inspection data to Yelp restaurant ratings.

- A Car Pal app that uses public data to alert drivers when to move their cars to avoid tickets from street sweeping.

- “Medical hot-spotting” to identify New York hospitals with the highest mark-up rates.[4]

- Using federal data from HealthData.gov to provide patients with more accurate information on local physicians who “over-treat” with unnecessary or inappropriate medical treatments.

- Evacuating and transferring patients during the Hurricane Irene disaster with the help of New York’s nursing home bed census data.[5]

- Improving pedestrian safety in San Francisco through data analytics.[6]

Further, the benefits of open data do not just accrue to external users; they can also improve governments’ internal operations. Government agency staff have told us that making their data available on public platforms can break down internal data silos, reduce Freedom of Information Act requests for data, and improve data quality as staff prepare metadata (“data about the data,” such as the years covered, variables included, and data dictionaries) and more users examine the data and identify errors.[8] Centralized repositories such as Data.gov can also be a valuable inventory of data assets, which can facilitate data sharing and find ways to combine data for new purposes.

Making open data publication a routine government activity is essential for making open data programs successful.[9] Health Data NY, the first state open data portal devoted to health, started as a small website with five datasets. It gained traction after Governor Andrew Cuomo issued Executive Order 95, which (1) required that all state agencies publish their data to the centralized Open NY portal; (2) called for the development of an Open Data Handbook to provide a vision and establish standards and governance; and (3) created the new role of chief information officer, among other actions. Health Data NY was also codified as a routine public health activity by making it a permanent part of the New York State Department of Health’s Office of Quality and Patient Safety and assigning dedicated staff to it. These changes at the policy and programmatic levels have allowed Health Data NY to become a national leader in making government health data easily accessible and maintain its visibility after the program’s founding health commissioner left state service in 2013.

There have been considerable fears about government data being removed from federal websites under the new presidential administration. Yet working in favor of this bill is its bipartisan sponsorship and support and its strong alignment with the mission of the bipartisan Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, which was jointly sponsored by Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA).

Time will reveal the fate of the OPEN Government Data Act as it currently awaits action by the House. But given the complexity of the federal government and the lessons from New York and other open data leaders across the country, this bill represents a promising strategy to coordinate open data publication activities and improve the discoverability, accessibility, and usability of government information.

Additional Readings

For more information on the OPEN Government Data Act, see:

- Open Government Data Act set for progress in 2017 after Senate passage (Samantha Ehlinger, fedscoop, December 12, 2016)

- OPEN Government Data Act to get another chance (Samantha Ehlinger, fedscoop, March 23, 2017)

- H.R.5051 – OPEN Government Data Act — 114th Congress (2015-2016)

- S.2852 – OPEN Government Data Act — 114th Congress (2015-2016)

[1] Peter R. Orszag, Memorandum to the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies, Subject: Open Government Directive, December 8, 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/memoranda_2010/m10-06.pdf

[2] Data.gov, “Data Catalog,” 2017, https://catalog.data.gov/dataset.

[3] Erika G. Martin and Grace M. Begany, “Opening government health data to the public: benefits, challenges, and lessons learned from early innovators,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 24, 2 (2017): 345-51, https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/jamia/ocw076.

[4] Crain’s New York Business: Health Pulse Extra, January 8, 2014.

[5] E.G. Martin, N. Helbig, and N.R. Shah, “Liberating data to transform health care: New York’s open data experience,” JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association311, 24 (2014): 2481-2.

[6] Cheryl Wold, “In Plain Sight: Is Open Data Improving Our Health?” California Health Care Foundation, January 2015, http://www.chcf.org/publications/2015/01/in-plain-sight-open-data.

[7] Illustration adapted with permission from Natalie Helbig.

[8] Martin and Begany, “Opening government health data to the public.”

[9] Erika G. Martin, Nirav R. Shah, and Guthrie S. Birkhead, “Unlocking the Power of Open Health Data: A Checklist to Improve Value and Promote Use,” Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 2017 (Forthcoming), http://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00124784-900000000-99610.