In November, we took a deep dive into the US care workforce and the people and occupations that make up this critical sector of the economy. Care workers are responsible for maintaining the education, health, and general welfare of the population, and a skilled care workforce is crucial not only to the well-being of individuals and communities but also the functioning of the economy. These are the workers who keep us healthy, watch and educate our children, and care for our aging family members.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and exacerbated pre-existing issues in maintaining and expanding this workforce. Prior to the pandemic there was already a shortage of nurses, childcare workers, home health aides, and teachers. These shortages only got worse over the course of the pandemic, and all of these occupations are expected to see substantial growth in demand over the next 10 years.

In the report, we take an innovative approach to defining the care economy. Instead of studying the healthcare and education industries or sectors, our report looks at the jobs and workers themselves. The crucial factor that ties these occupations together is that they all rate “assisting and caring for others” as one of the most important work activities, and for the majority of the occupations, it is listed as the most important work activity. These are the workers that support people’s necessary functioning and human capabilities from birth to death.

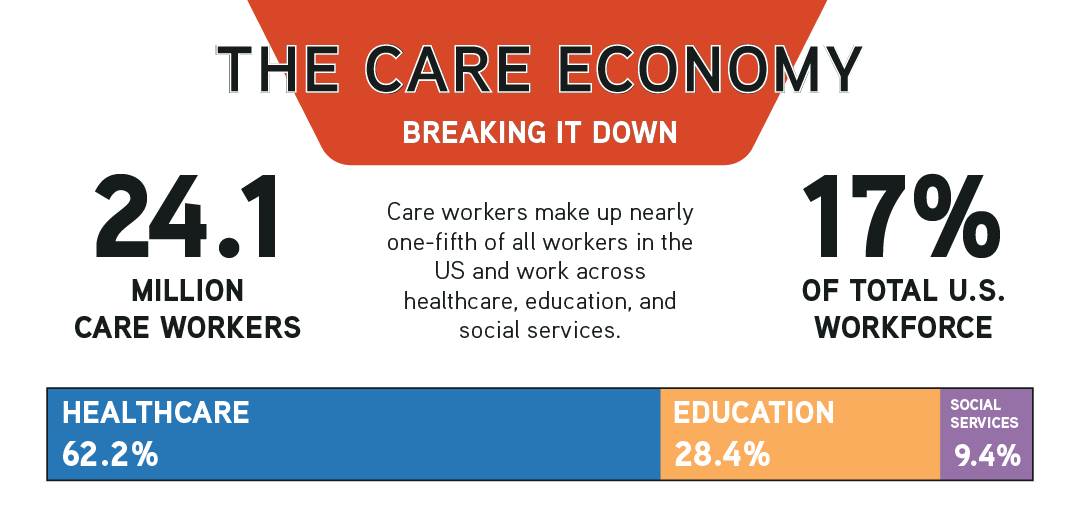

This approach allows us to better understand the workers who provide the direct care people require. Together, they make up 17 percent of the total US workforce and include workers across the entire education and training spectrum—ranging from those who have less than a high school diploma to those with multiple advanced degrees and post-degree training. By understanding the people who provide these critical services, we can create more effective policies to attract and retain these workers as they continue their important roles.

This blog highlights five of the most important takeaways for policymakers from the report.

-

The care workforce spans direct care occupations across three employment sectors

The care workforce includes workers in the healthcare, social services, and education and childcare industries, but we do not consider every worker in those sectors to be a care worker. For example, in a school district the teachers and aids are included in our definition of the care workforce, but the financial officers and human resource professionals are not. In an industry-based approach, all people employed by a care-related entity would be included, regardless of the nature of the work they perform.

The care workforce is large, consisting of 24.1 million workers in 2020, and accounting for 17 percent of the total workforce. Healthcare practitioner and technical support occupations make up 26 percent of the care workforce, healthcare support occupations make up 27 percent of the care workforce, and education occupations make up 26 percent with the remainder in social sciences and social services.

Number of Occupations and Employees across Sectors of the Care Workforce

-

Large differences in education requirements mean large differences in wages

The care workforce is made up of occupations that require vastly different levels of education and training. Physicians, nurses, teachers, social workers, and psychologists require higher levels of education and earn higher annual pay. In contrast, positions such as childcare workers, home health aides, and human services assistants have fewer requirements and earn lower pay.

Typical Education Requirements and Average Annual Wages for Select Care Workforce Occupations

Healthcare practitioners all require a professional degree and training experiences, such as residencies. This sector of the care economy earns the highest average earnings. Healthcare technicians don’t necessarily require an advanced degree but often require a specialized associate’s degree or training program. Jobs in healthcare support generally only require a high school diploma or, at most, a post-secondary non-degree certificate.

The education workforce has a similar earnings pattern with the K-12 teachers earning the highest salaries. In contrast, educational support workers earn substantially less. Teaching assistants and childcare workers are not required to have a post-secondary degree, although most teaching assistants have some college but no degree.

The community support services workforce is substantially smaller than education and healthcare with fewer distinguished occupations. Much like education and healthcare, the highest earning occupations require advanced degrees. Clinical psychologists are the highest earners at $89,000 per year and are required to have a doctorate or professional degree. Other high earning professions require a master’s degree and include social workers earning $52,000 - $60,000 depending on specialization. Some social services support occupations, such as social and human service assistants and community health workers, do not require formal education beyond high school but generally require significant on-the-job training.

The education requirements and higher wages paid to specialized and credentialed professionals in healthcare, education, and community and social services mean that many of the individuals are unlikely to leave the care workforce. However, support staff that do not have specialized training and receive relatively low pay may consider employment in other sectors of the economy. Childcare workers, for example, may find higher levels of compensation in the retail or hospitality industries that also employ workers with a high school education.

-

Four in five care workers are women

The most striking difference between the US care workforce and the total workforce is the gender balance. Over the past 20 years, the care workforce has been 79 percent women compared to the overall workforce which is only 47 percent women. Nearly one in four (23 percent) of working women have jobs in the care workforce compared to only six percent of men.

Black women in particular play an outsized role in the care workforce. Black women are 6 percent of the overall workforce but 12 percent of the care workforce. They are 19 percent of social workers, 10 percent of registered nurses, 7 to 14 percent of teachers (depending on grade level), 32 percent of nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides, and 23 percent of licensed and vocational nurses.

Overall, the women in the care workforce are somewhat better off than women in the general workforce based on a number of indicators. When compared to their peers in other sectors, women in the care workforce are more likely to

- have a bachelor’s degree or higher (54 percent compared to 34 percent),

- own their own homes,

- have health insurance,

- be geographically stable, and

- be pursuing additional education.

Women in the care workforce are slightly more likely to have family obligations. Women in the care workforce are more likely to be married, have children living in the home, and to have pre-school aged children living in the home when compared to women in other occupations. More than half (52 percent) of women in the care workforce have a child living at home, and working mothers make up 41 percent of the total care workforce. This means that care workers felt a greater impact from the COVID-19 pandemic school disruptions and the ongoing childcare shortages. Understanding the demographic profiles of care workers can help policymakers understand the barriers they face and develop programs to retain and attract new workers into the care economy.

-

The New York care workforce has a higher percentage of workers of color and non-native born workers than the US care workforce as a whole

New York’s care workforce looks similar to these national trends. New York care workers earn 17 percent more than the national average. (New Yorkers earn 20 percent more than the national average across the workforce). This difference is driven by the higher cost of living and New York’s higher than average minimum wage. Healthcare aides in New York, who are often paid at or near the minimum wage, earn 30 percent more than the national average. Teachers also have substantially higher wages in New York earning 29 percent more than the national average.

The main difference between New York and the rest of the country, however, is who the care workers are. The care workforce accounts for 20 percent of New York’s workers (compared to 17 percent nationally). New York’s care workforce is significantly less white—forty percent of New York’s care workers are people of color compared to 32 percent nationally. Care workers in New York are 12 percent less likely to be white, 50 percent more likely to be Black, and 13 percent more likely to be Hispanic. Immigrants and first generation Americans also make up a much larger component of New York’s care workforce; twenty-nine percent of the care workforce in New York are immigrants and an additional 8 percent are children of immigrants. This is more than twice the rate of the national care workforce which is 14 percent immigrant and 4 percent first generation.

-

Nationally, the care workforce is expected to grow dramatically in the next ten years with support workers in the highest demand

The demand for care workers is projected to grow by 10.5 percent over the next decade nearly twice the projected growth across other occupations (5.3 percent). The US population is aging and the number of Americans over 65 is expected to double in the next 40 years and 70 percent are expected to need some sort of long-term care. This dramatic shift has led the Bureau of Labor Statistics to predict that seven times as many home health aides will be needed by 2030 and we will need at least three times as many registered nurses, nursing assistants, and pharmacists over that same time period.

Healthcare is not the only sector of the care workforce that expects high levels of future demand. The number of teachers needed is expected to double by 2030 driven partly by increased provision of pre-school education by states and school districts in addition to the standard K-12 services. Virtually all occupations within the care workforce are expected to grow faster than the national average, including counselors and social workers (14 percent) and substance abuse counselors (23 percent). Of the 106 occupations included in this study, only two are expected to grow at a rate below the national average: dispensing opticians and pharmacy technicians.

Over the next ten years, the number of care workers needed is expected to increase dramatically and we are already facing worker shortages. Attracting new workers to this industry and providing the education, training, and support that they need to be successful is a complex undertaking that will require coordination across industries and in both the public and private sectors.

Conclusion

The care workforce is a vital and growing part of the US economy and the people (mostly women) who work in these occupations are crucial to the functioning of the economy as a whole. This blog and our larger report is intended to serve as a jumping off point for these necessary discussions by furnishing a detailed description of the care workforce, its occupations, and its workers. We believe that the significance of these occupations both as large sectors of the US economy and as supports to the functioning of the rest of the economy necessitates that they are discussed holistically rather than as individual industries.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leigh Wedenoja is senior policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute of Government