In Part 1 of our series, we defined biosolids and described their production and use nationally and in New York State. In Part 2, we describe the broader federal regulatory history of biosolids and the existing regulatory process.

From Ocean Dumping to Circular Use

Until 1972, ocean waters were commonly used for the disposal of different kinds of waste including sewage sludge in the US (and elsewhere). Sewage sludge, a byproduct of wastewater treatment made of organic material (similar to compost), is a broader term sometimes used interchangeably with biosolids. But biosolids, as discussed in Part 1, refer more specifically to treated sludge that meets certain standards and is sometimes applied to land, including agricultural land, in the United States. Though biosolids as a term has only been popularized since around 1990, similar soil amendments have been used in agriculture since the 1920s due to their ability to enhance soil properties. In 1968, roughly 4.5 million tons of sewage sludge was dumped into the ocean in the US. This was in addition to barrels of radioactive waste and tens of millions of tons of other wastes (dredged material, industrial wastes, construction, and demolition debris), as well as wastes that were even more significant in weight dumped by vessels or pipes (including petroleum products, heavy metals from industrial wastes, acid chemicals from pulp mill waste, and organic chemicals).

The Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (MPRSA) first regulated the dumping of such wastes, including sewage sludge, in the ocean through permitting—though it did not prohibit it. The 1987 Clean Water Act Amendments then directed the EPA to develop new regulations to address “reasonably anticipated adverse effects of certain pollutants that might be present in sewage sludge biosolids.”

Those regulations would not be finalized for six more years. But the following year—in 1988, while regulations under the Clean Water Act were still in development—the Ocean Dumping Ban Act was enacted. That Act amended MPRSA to prohibit the dumping of municipal sewage sludge, as well as industrial and medical wastes, in the ocean. While this prevented those types of waste from being disposed of in the ocean, there still remained a significant amount of such waste being produced each year that needed to be addressed or redirected.

In the context of the ocean dumping ban, biosolids became one way to deal with the resulting ‘excess’ sewage sludge within the framework of a circular economy—in which materials, rather than being treated as ‘waste,’ are kept in circulation in a closed-loop or circular system.

The Biosolids Rule

As outlined in Part 1 of this series, some biosolids are applied to agricultural and other lands to enrich soil properties, particularly as they contain organic nutrients that support plant growth. As the EPA notes, “land application of biosolids also can have economic and waste management benefits (e.g., conservation of landfill space; reduced demand on non-renewable resources like phosphorus; and a reduced demand for synthetic fertilizers).” However, such applications may also have risks if pathogens and pollutants in wastewater systems aren’t adequately researched, monitored, or regulated.

Drawing from the 1987 Clean Water Act Amendments, in 1993 the first federal regulations for biosolids were finalized. This new rule, which fell under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program under the Clean Water Act’s Standards for the Use or Disposal of Sewage Sludge (40 CFR part 503), was referred to as the Biosolids Rule.1 At the time the rule was finalized, nine heavy metals were regulated under it.

Class A and B

These federal regulations classify biosolids as either Class A or Class B according to their management and treatment for pollutants, pathogens, and other qualities—though states may have more stringent regulations. Class A biosolids undergo treatment processes to reduce the presence of pollutants to below regulatory limits. Class A biosolids are also treated to eliminate pathogens (disease-causing organisms) as well as vector attractions (agents) that spread pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, parasitic worms, and protozoa (single-celled organisms that include parasites).

Class B biosolids also undergo treatment, but they may still contain pathogens. As a result, there are further site restrictions regarding the land application of Class B biosolids regarding their use (like allowing time for pathogens to degrade). There are also different pollutant standards for use and disposal depending on what type of disposal is being used for biosolids—i.e. whether it is land applied, surface disposed at a landfill, or incinerated (for sewage sludge).

Regulatory Process

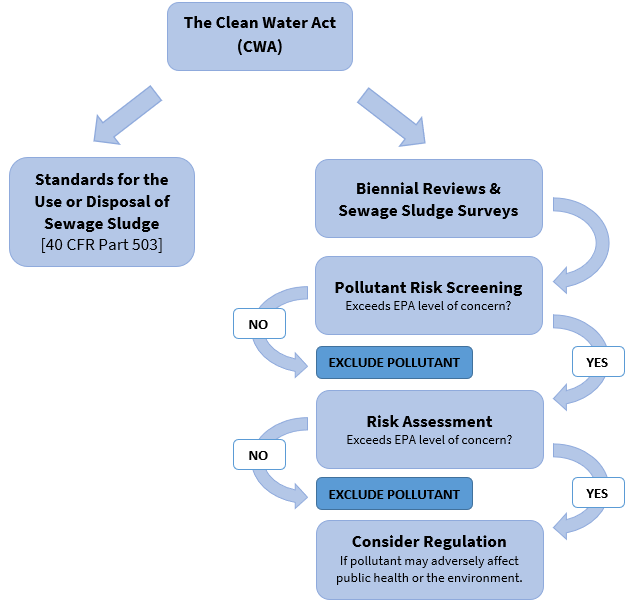

The pollutants that are regulated under the Biosolids Rule are identified through a review process that is outlined by the rule. The EPA is required to conduct a review of biosolids regulation at least every two years (under Section 405(d)(2)(c))) to identify additional toxic pollutants and promulgate regulations to address them. The EPA Office of Water’s Office of Science and Technology (OST) is responsible for conducting this review, referred to as the Biosolids Biennial Review.

How Biosolids Are Regulated

Source: “Biosolids Laws and Regulations,” US Environmental Protection Agency.

The underlying law (the Clean Water Act) provides that the EPA “shall identify those toxic pollutants which on the basis of available information on their toxicity, persistence, concentration, mobility, or potential for exposure, may be present in sewage sludge in concentrations which may adversely affect public health or the environment and propose regulations” (Sec. 405 (d)(A)(i) of the Clean Water Act). This review then acts as the basis for further risk screening and assessment, from which the EPA decides whether or not to regulate a given pollutant. However, it is important to note that in this process the EPA is not required to produce the data necessary to complete the review of any potential contaminants, including those known or presumed to enter wastewater systems, it is only based on available research that meets a certain criteria.

Literature Search Criteria, EPA’s 2015 Biosolids Biennial Review

Biosolids-related keywords: (sewage sludge OR biosolids OR treated sewage OR sludge treatment OR sewage treatment)

AND

Pollutant- and health realted keywords: (pollutant* OR toxic* [toxicant, toxicology, etc.] OR pathogen* OR concentration* OR propert* OR fate OR transport OR health OR ecolog* OR effect OR effcts OR micro* [microbial, etc.] OR Salmonella)

AND

Geographic keywords (limiters): (United States OR Canada OR USA OR U.S.A. OR U.S. OR US)

AND

Land Application-related keywords: (land application OR farm OR agriculture OR soil)

AND

Health-related keywords: (occurrence OR concentration OR properties OR fate OR transport OR health effects OR ecological effects).

The EPA may conduct a Sewage Sludge Survey in which it uses samples from wastewater treatment plants to detect the presence of potential pollutants at this stage in the regulatory process. However, the most recent survey was conducted in 2006, with prior surveys conducted in 2001 and 1988.

If, on the basis of the information found in the Biosolids Biennial Review and any potential Sewage Sludge Survey, the EPA determines that a pollutant is identified in biosolids from wastewater treatment plants then it will conduct a Pollutant Risk Screening to determine the levels at which a pollutant is present. And, if a pollutant is found to be present at a level exceeding the EPA’s level of concern, the agency will then conduct a risk assessment2 to determine the “chance of harmful effects to human health or to ecological systems resulting from exposure.”

Once such a risk assessment is complete, the EPA may then make a determination to regulate or exclude a pollutant under the Biosolids Rule. As will be discussed further in the next part of this series, however, this process has not produced any newly regulated pollutants in over twenty-five years. The next parts in this series will further explore why this is the case and the documented shortcomings of the Biosolids Program, before outlining the discovery of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) chemicals—commonly referred to as “forever chemicals“—as pollutants in biosolids and current efforts to address them through regulation.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Laura Rabinow is deputy director of research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Francis Ofori-Awuku is a graduate research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government and a PhD student in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at the School of Public Health, University at Albany (SUNY)

[1] As referenced in Part 1, the EPA is the permitting authority for 41 states under the Biosolids Rule, including New York, while nine state are designated their own permitting authority for biosolids (Arizona, Idaho, Michigan, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin).

[2] The EPA has outlined three types of data the agency needs to inform its risk assessments. These include data on (1) occurrence and concentration of pollutants in biosolids (necessitating the analytic capability to detect them in biosolids and determine their concentrations); (2) toxicity to human and ecological receptors (as defined by referenced dose, reference concentration, cancer slope factor, lethal dose, and lethal concentration, or chronic endpoints); and, (3) environmental fate and transport for those pollutants. (2015 BBR, 2)