During the spring 2020 academic term, school closures were announced in many states in efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic. At the present time, a number of schools remain completely or partially closed to in-person instruction and more districts have announced they will not return to full in-person learning in spring 2021. Many districts are also implementing hybrid models that include partially opening for a few hours per day for two to four days per week, and others are implementing alternatives such as limited outdoor classes in parking lots and temporary shelters, learning pods, or individualized home instruction.

The pandemic has led to a high percentage of students nationwide being compelled to learn at home using distance learning strategies. Guidance from the US Department of Education permitted school districts to make decisions on the strategies they may implement based on their assessment of the local situation. They encouraged the implementation of distance learning approaches for all students, including students with special education needs, while permitting districts the flexibility to make modifications to specialized instruction, as long as it remained “appropriate.” The guidance statement clarified that if general education students were receiving remote instruction, this could be considered appropriate for special education students as well.

Remote/Hybrid Instruction for Students With Special Education Needs

The consequences of school closures are particularly grave for the approximately 7,134,000 students in special education programs (14 percent of the US school-age population). They include students with many different learning needs based on their diagnostic classification (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Students With Disabilities Served under the Individuals With Disabilities Education (IDEA) Act, 2019

* Percent Within All Students with Disabilities: .001%

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics.

As of the most recent data from the National Center For Education Statistics, some 95 percent of 6- to 21-year-old students with special education needs were served in public schools (62.5 percent of whom were placed in general education inclusive classroom settings for some part of the school day), 3 percent were served in a separate school for students with special education needs, 1 percent were placed in regular private schools by their parents or guardians, and less than 1 percent were served in one of the following environments: separate residential facility, homebound or in a hospital, or in a correctional facility. The majority of these students are now receiving their educational program partially or fully at home, implemented by parents, siblings, other caregivers, or visiting teachers.

The Learning Needs of Students in Special Education

Many students with special education needs have a greater need for teacher contact and direct instruction than their peers in general education classes. By definition, their educational programs are either unique to their particular needs or a modified version of the general education curriculum, in terms of content, pacing, and mode of delivery. The extent to which a student is provided with specialized or modified services and instructional supports is defined on each child’s Individual Education Plan (IEP), a document compiled by educators, school administrators, therapists, other specialists as necessary, and the parents or guardians of the child, as mandated by the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). A student’s IEP indicates the extent to which they are educated in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE), most often defined as the general education classroom with instruction from special educators and therapists for some or part of the school day. More restrictive (less inclusive) environments such as separate classes or separate schools are recommended only for students who are not likely to benefit from placement in a general education setting due to cognitive or behavioral challenges, or due to needing a curriculum of self-care and vocational training.

Continuum of Services for LRE Placement

The New York State Education Department, in accordance with IDEA mandates, has defined a continuum of services that may be offered by school districts as set down in their IEPs. These services vary widely based on a student’s needs and can include programs during the school day to support students with special education needs both in general education classrooms and special education classrooms as well as after school supplemental programs. These services have a wide scope and include programs that support student learning through modifying curriculum or assessments, access to additional behavioral and instructional support staff, providing specialized therapies like speech-language pathology and occupational therapies, and specialized classrooms for students who receive instruction separate from their nondisabled peers.[1]

Special Education At Home

Students with special education needs are now being educated largely at home via instructional materials and supports sent by schools for part or all of the school day. Rather than receiving individualized attention directly from teachers, it now falls on parents, guardians, and caregivers to implement specialized instructional programs at home with their children. In school, the continuum of services discussed above relies on many different types of specialized personnel that have been trained to work with students with special education needs including general education teachers, special education teachers, para-professionals, speech pathologists, therapists, doctors, nurses, and social workers. But for home-based instruction, a parent, guardian, or caregiver must take on all these roles, along with juggling their own work demands at home or outside the home, the care of other children, and family needs for health, meals, and emotional support.

The enormous strain caused by the combination of these responsibilities cannot be underestimated. Daily trade-offs must be made between work and family priorities resulting in guilt, fatigue, feelings of failure, anxiety, and even depression. In a survey of 405 families conducted by the Parenting In Context Research Lab at the University of Michigan, the major stressors identified by parents during the pandemic were economic uncertainty related to possible job loss and disruptions to children’s schedules. Working mothers have been most impacted by the move to remote learning from home, with almost 69 percent of mothers having to take leave or make job modifications due to childcare demands. Over one-third of all working women with children at home surveyed reported feelings of anxiety and worry.

The delivery of instruction at home by family members typically consists of a teacher or therapist sending home instructional materials and the parent or guardian implementing the learning activities. This approach is built on multiple underlying assumptions that may not be true, or only partially supported, in many cases. The first set of assumptions are related to the degree that the home is conducive to completing schoolwork. This means that the student must have access to technology, reliable Wi-Fi access, and other related equipment such as communication devices, and the student must have an appropriate space with the required adaptive supports and seating. The second set of assumptions are related to the parents, guardians, or caregivers, who must have the time to implement and oversee the remote learning, and teaching and therapy skills necessary to deliver the required interventions. Finally, this approach relies on the assumption that the child is willing and able to participate in remote learning. If not, this means additional work by parents or guardians to get the child seated at a computer, have them engage in the learning activity, and keep them on task.

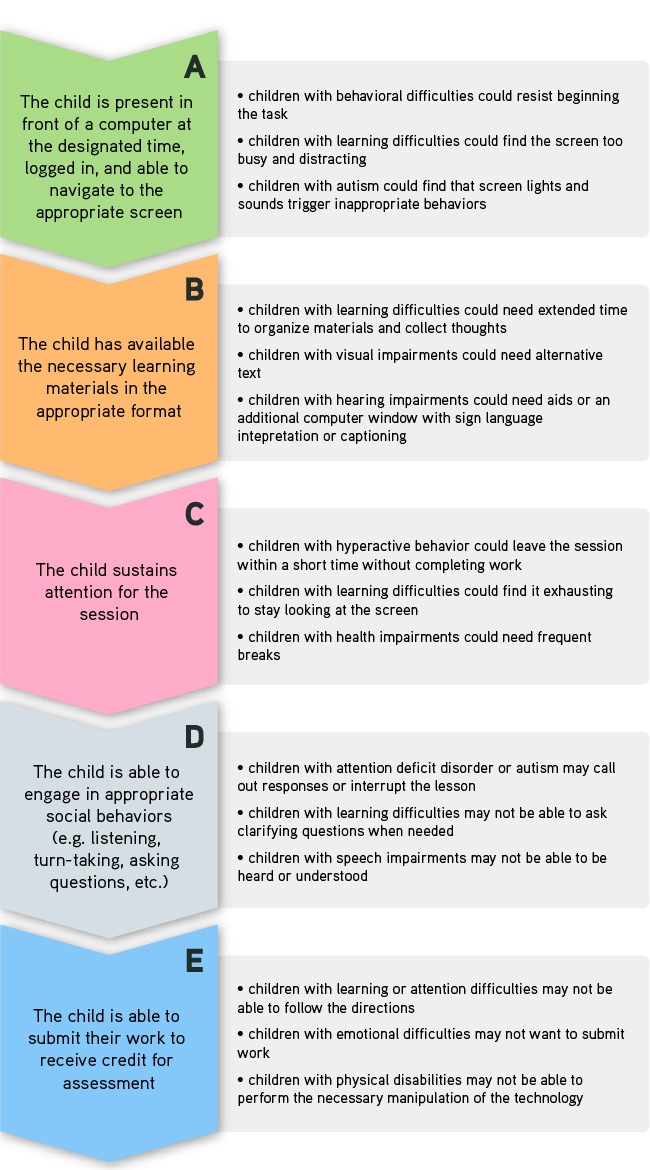

Accommodations and interventions recommended for students on their Individualized Education Plans vary according to learning needs but may include practices that are very difficult to implement by parents who are not trained educators in a typical home setting. Consider the illustration of learning needs listed in the graphic below, which would need to be repeated several times a day for the length of the home-based instruction.

Figure 2. Example of Home Instruction Needs

The strategies used by teachers and other professionals to try and address these needs and behaviors may, however, be very challenging for parents to implement at home and could include:

- Instructional modifications: breaking down information into smaller (15 minutes or fewer long) learning activities; scaffolding from large concept to smaller details within each unit; color-coding or using other organizational aids for each topic within each subject area; practicing skills in varied formats (words, pictures, gestures); providing immediate feedback; using a variety of instructional software.

- Assessment accommodations: providing extended time (60-90 minutes) in a quiet environment; assistance with physical responses through writing or filling bubbles without answering for the child; translating to sign language, symbolic language, or use of large print.

- Environmental adaptations: setting up flexible/adaptive seating for appropriate support and visibility; maintaining a daily instructional schedule and weekly calendar; allowing a few minutes of movement after every session of schoolwork (and resetting timers accordingly); maintaining a monitoring record for learning and behavioral goals; using hearing, speech or visual aids for reading and communication; providing a quiet space without distractions.

- Therapeutic interventions: implementing speech and articulation development techniques, some which require mirrors or special equipment; conducting large and small motor development activities using exercise equipment; facilitating counseling and psychiatric services.

- Participation in parent-teacher conferences: attending meetings without full command of conferencing technology; inability to have questions clarified or jargon explained; collecting and providing the requested assessment/monitoring data; dealing with a sense of blame if they are not able to implement programs fully at home.

Preliminary Reports of Effective Home Instruction

A report published by the American Institutes for Research, based on a survey of 744 school districts, revealed that a majority of responding districts felt that school closures during the current pandemic made it difficult for them to provide supports to students with special education needs in terms of hands-on services (82 percent), instructional accommodations (73 percent), and engaging families for help in meeting IEP requirements (57 percent). On the other hand, the responses were somewhat surprising in that many districts (over 40 percent) felt they were able to comply with IDEA mandates for services. This perspective contrasts with information from parents, who report considerable difficulties in implementing home-based instruction.

The loss of learning over summer vacations for students is a documented phenomenon, despite the provision of several weeks of summer classes each year at schools for special education students to maintain literacy and other academic and self-care skills. However, there has not been a situation in modern history where schools have not convened in person for almost a year. Middle- and upper-income students typically do not have as steep a learning loss as students from lower-income families, due their participation in paid summer activities that involve learning such as technology, arts, or science focused camps. However, many summer school and summer camp programs could not be implemented this year because of pandemic-related closures and restrictions. No research exists as of yet on the actual impact of such a long closure on the academic, social, behavioral, or physical growth of students with special education needs, particularly those from lower-income families. However, it may be anticipated that considerable learning loss will be evident when accountability assessments resume—although that may not take place until spring 2022.

Parent Voices

Parents and guardians of students with special needs and their advocates have expressed frustration with the current situation and called for additional support. One of the top requests of parents and guardians was daily interactions between students, teachers, and therapists. They felt that regular interactions through email, FaceTime, and video chats are necessary to maintain students’ relationships with educators and prevent regression. In addition, parents asked for guidance and strategies that would help them more effectively execute remote learning plans such as:

- Academic instruction: Strategies to present information in engaging ways based on the material provided.

- Physical, occupational, speech, or other therapy: Strategies or videos on how to effectively use adaptive communication devices (e.g., Braille, ASL) or therapeutic techniques (e.g., speech exercises, physical exercises), and ways to motivate students to persist.

- Behavior management: Strategies to have students attend and engage while receiving online instruction and remain on-task.

- Social and emotional skills: Strategies to assist students in appropriate online interaction with teachers and peers including listening, turn-taking, conversing, and responding.

- Record keeping: Strategies to track student progress and maintain records.

- Parent involvement: Strategies to maintain continuous communication with parents for modifying individual education plans and other related decision-making.

- Emotional support for parents: Strategies to deal with fatigue, frustration, and other emotions related to attempts to keep up with schoolwork.

“But no amount of love and care at home can turn the average parent into a special-education teacher overnight. Nor can it enable them to practice occupational, speech, or physical therapy…”

Faith Hill, The Atlantic, April 18, 2020

School Responses

Teachers are engaged in extraordinary efforts to reach and teach students, including online class sessions in small groups, one-to-one instructional time, in-person instruction at school where possible, and even “porch visits” to student homes. School administrators have developed creative organizational models to support in-person instruction where possible and the delivery of resources to parents. Many educational publishers, associations, and agencies have stepped forward to offer free materials and resources for educators.

One District’s Experience

Yonkers Public Schools is an example of how a district can be proactive in meeting the needs of their parents and students of special needs. Yonkers is a large diverse urban district with high levels of families in poverty (76 percent), which serves approximately 4,575 students with special learning needs. Dr. Luis Rodriguez, Assistant Superintendent for Special Education and Pupil Support Services, held a number of virtual town hall meetings for parents to help them identify “Look For’s.” These are procedures that teachers and therapists should be following when delivering remote instruction, for example, providing visualization and simulations, making connections to the real world, and supporting social development management needs. The goal was to help parents evaluate how the district was meeting the needs of students in the provision of instruction and support services using hybrid or remote learning. The district both directly and through their parent-teacher association (YSEPTA) continues to provide training and support for parents through guidance videos, remote instruction assistance, and support, as well as access to many district and state learning resources for children (personal communication, Nov. 12, 2020).

The efforts of the education community have been very commendable, but do not change the reality for parents who have had to make major changes in their lives to become educators for their children. At some smaller districts on Long Island, parents have come out in protest of school closures, stating that their children’s education is at risk, as well as their difficulties in managing young children at home when they need to be at their own jobs. On the other hand, school administrators have attempted to juggle public health guidelines with providing educational services, citing the immense budgetary burden of reopening with more personnel, building renovations, and health precautions that would be necessary should students receive in-person instruction on a regular schedule.

Policy Responses

While individual teachers, schools, and districts have been responsive to the concerns and needs of parents, additional support is needed from policymakers. On July 20, 2020, the National Association of State Directors of Special Education joined the National Governors Association and other leading organizations to request additional funding to enable the reopening of schools with appropriate health precautions. Shortly thereafter, the US Department of Education announced the Rethink K-12 Education Models Grant, through which New York State received almost $20 million for teacher and school leader professional development to effectively implement remote or hybrid learning for all students. Phase 1 of the state plan includes six core competencies of providing remote/hybrid instruction:

- Shifting to teaching online;

- engaging families as partners in remote/hybrid learning;

- meeting the needs of students with disabilities through remote/hybrid learning;

- meeting the needs of English language learners/multilingual learners through remote-hybrid learning;

- integrating culturally-responsive sustaining education (CRSE) in remote learning environments; and

- integrating social emotional learning (SEL) in remote learning environments.

Further federal support is being considered. There is a proposal currently in the US Senate, called the Learning Opportunity and Achievement Act (LOAA), to consider funding for teacher professional development for distance learning, with a particular focus on students from disadvantaged groups, including students with special education needs. And, additional funding for education has been integrated into stimulus bill proposals.

Parents of special needs children have identified a need for training and guidance that would assist them in the educational implementation of specially designed instruction. To date, no funding has been specifically allocated for training and other programs that support parents and guardians in implementing remote/hybrid learning. Such programs would, however, support the underlying competencies outlined in the New York State plan. Given the recent studies and experiences noted above, an investment in programs to assist families of students with special education needs in remote/hybrid learning might address some of the most frequent challenges cited by families and stand to benefit both students and those assisting them. This may not only benefit such families in the immediate, but better position them as they begin to shift their focus towards recovery.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

René S. Parmar is a Richard P. Nathan public policy fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government and a professor of instructional leadership at St. John’s University, New York.

[1] Detailed discussion of New York State Education Department’s Continuum of Services is available at: http://www.p12.nysed.gov/specialed/publications/policy/schoolagecontinuum-revNov13.htm.