August 31, 2017

This term, the Supreme Court will hear the case of Gill v. Whitford, a Wisconsin partisan gerrymandering challenge.1 While Whitford has understandably captured the attention of those interested in redistricting issues nationwide,2 a potential route to bring partisan gerrymandering challenges closer to home has gone largely undiscussed. In 2014, New York voters amended the state constitution to enact a host of redistricting reforms — including language prohibiting drawing lines on the basis of partisanship. This amendment may prove to be a powerful tool to bring state court challenges to New York’s lines.

Any state or federal partisan gerrymandering challenge exists in the shadow of Vieth

v. Jubelirer, a 2004 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court sharply divided over the justiciability of partisan gerrymandering claims.4 The plurality opinion in Vieth, written by Justice Scalia and joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices O’Connor and Thomas, concluded that because “no judicially discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating political gerrymandering claims have emerged” since the Court’s decision in Davis v. Bandemer5 eighteen years previously, partisan gerrymandering claims should be treated as nonjusticiable.6 Justice Kennedy’s concurrence — the crucial fifth vote — concluded that even though he did not find the standard proposed in Vieth to be judicially discernible and manageable, he was not prepared to conclude that no standard could ever be.

While New York’s federal courts have occasionally been receptive to racial gerrymandering challenges to congressional lines in recent decades, they have not been receptive to partisan gerrymandering challenges, emphasizing that bipartisan gerrymandering is presumptively constitutional.

In a 1992 redistricting challenge to state legislative district lines, the Northern District of New York concluded that “the evidence show[ed] that the Assembly apportionment plan [at issue] was a result of a political compromise that allowed the Republicans to craft the Senate apportionment plan while the Democrats fashioned the Assembly plan,” and, as such, the plaintiffs could not convincingly argue that the Assembly plan would “consistently degrade Republicans’ ability to influence New York’s political process.”10 In a later case, the Southern District of New York highlighted the significance of New York’s bipartisan redistricting process,11 though it noted that it was not entertaining a partisan gerrymandering challenge to the 2002 lines.12 Most recently, the Eastern District of New York once again rejected a partisan gerrymandering challenge to New York’s state legislative lines; while it did not reference the bipartisan nature of the redistricting process, the court rejected the plaintiffs’ allegations of a partisan effect.

Nor have New York’s state courts been receptive to partisan gerrymandering challenges. In 1972, the Court of Appeals rejected partisan gerrymandering challenges to state legislative lines because even if it assumed such challenges were justiciable, the record in the case was insufficient.14 The court further added that the requirements of compactness, contiguity, and convenience were “adopted for the salutary purpose of averting the political gerrymander and at present are the only means available to the courts for containing that pernicious practice.”15 The Appellate Division has followed federal courts in its treatment of the justiciability of state-law political gerrymandering claims.

More recently, the Court of Appeals has been willing to find alternative motives underlying redistricting decisions, even where evidence may suggest partisan intent. In Wolpoff v. Cuomo, the Court of Appeals found no reason to hold that the 1992 lines were the product of anything but a “good faith effort” to comply with federal and state constitutional requirements, rather than “partisan political reasons.”

The court resoundingly endorsed the Legislature’s decision to balance conflicting federal and state requirements18: “It is not the role of this, or indeed any, court to second-guess the determinations of the Legislature, the elective representatives of the people, in this regard.”

Despite this unpromising history, the New York Constitution now provides a significant vehicle to challenge future lines. In 2014, New York voters amended the state constitution’s provisions concerning redistricting.20 The 2014 amendments were made without a constitutional convention, through its approval by two consecutive legislatures and by the voters of the state. Codified throughout Article III, the amendment sets forth a number of significant adjustments to the state’s redistricting process.

One of the most-discussed changes was the creation of a ten-member redistricting commission to draw both state and congressional lines beginning in 2020.21 The commission must consist of two members selected by the temporary president of the Senate, by the speaker of the Assembly, and by each of the minority leaders of the Senate and the Assembly.22 Those eight appointed members must then select the remaining two commission members. At least seven of its members must vote to approve a redistricting plan, with additional requirements that any plan must receive support from commission members nominated by both political parties.

Once approved by the commission, the plan goes to the legislature for approval. Each chamber must vote on the commission’s plan without amendment. If the first plan approved by the commission fails in the legislature, the commission must develop and approve a second plan for approval by each chamber without amendment. If the second plan fails in the legislature, the legislature can amend it only at that point. Most importantly, the constitution now requires that any amendments made by the legislature must comply with the substantive requirements discussed below, including the prohibition against partisan gerrymandering. In addition, in the chapter bill enacted with the constitutional amendment (L. 2012, c. 17), an additional restriction on the legislature was added: “Any amendments by the senate or assembly to a redistricting plan submitted by the independent redistricting commission, shall not affect more than two percent of the population of any district contained in such plan.” In other words, if the legislature rejects the first two commission plans, it can approve its own plan only by amending one of those plans on the margins.

If the commission cannot obtain the requisite votes for a redistricting plan, it is required to submit the redistricting plan or plans and implementing legislation that obtained the most votes to the legislature,24 which may then approve the plan.25 The amendment further imposes supermajority vote requirements on the legislature for the approval process, which vary depending on whether the commission was able to approve a plan or whether it merely submitted the best (but unapproved) option.26 Most importantly for future partisan gerrymandering challenges, the 2014 amendment imposed further limitations on what factors may be considered in drawing lines. Among other restrictions, the constitution now requires that “[d]istricts shall not be drawn to discourage competition or for the purpose of favoring or disfavoring incumbents or other particular candidates or political parties.”27 Based in part upon similar language in Florida’s Constitution,28 the provision was drafted to provide a concrete basis for a potential future29 court challenge to district lines drawn for partisan advantage.

Any such challenge would likely mirror a suit challenging Florida’s 2012 redistricting plan, brought under the Florida Constitution’s similar provision. In League of Women Voters of Florida v. Detzner, 30 the Florida Supreme Court considered various forms of smoking-gun evidence, including persistent efforts by state legislators to keep political operatives “in the loop” during the state’s redistricting process.31 Emphasizing its prior holding that the Florida Constitution’s text sets “no acceptable level of improper intent,”32 in contrast to the Supreme Court’s requirement of “invidious” discrimination,33 the court concluded that the direct evidence of unconstitutional intent merited redrawing certain districts shown to be drawn for political reasons.

Here too, plaintiffs may raise a challenge to New York’s districts based on evidence of partisan intent during the redistricting process. Negotiations between legislative leaders, and with their own party conferences within each chamber of the legislature, over specific district lines — as well as draft statistical analyses to help craft districts to protect or undermine a party’s hold on a legislative seat — are now likely to become constitutionally relevant. Similar analysis should apply to the workings of the redistricting commission, in order to ensure that it fulfills its mandate. While nothing in the constitution requires those involved to preserve their documents created during the redistricting process, the near certainty of a litigation challenging the district lines should support an argument that such an obligation exists from the start of that process under existing federal and state case law governing document preservation. Because the language of the 2014 amendment unqualifiedly prohibits the drawing of districts to further partisan goals, courts should now have a constitutional basis to curb partisan gerrymandering in ways they previously could not. Plaintiffs may seek to challenge any demonstrable partisan intent, relying on reasoning similar to the Florida Supreme Court’s in arguing that there is no need to set an “acceptable level of improper intent.”

Moreover, future challenges to New York lines under this provision of the state constitution may be bolstered by use of an “efficiency gap” analysis. The “efficiency gap” (EG) is one potential metric for assessing the partisan effects of a redistricting plan, and has recently been used in redistricting challenges.36 The plaintiffs in Whitford, for example, raised it as possible evidence of partisan gerrymandering regarding Wisconsin’s lines. As the district court explained in Whitford:

The efficiency gap is the difference between the parties’ respective wasted votes in an election, divided by the total number of votes cast. When two parties waste votes at an identical rate, a plan’s EG is equal to zero. An EG in favor of one party, however, means that the party wasted votes at a lower rate than the opposing party. It is in this sense that the EG arguably is a measure of efficiency: Because the party with a favorable EG wasted fewer votes than its opponent, it was able to translate, with greater ease, its share of the total votes cast in the election into legislative seats.

Votes can be “wasted” in two ways: either by being cast in favor of a losing candidate, or by being cast in excess of the majority needed for a winning candidate to reach victory.38 If a district is heavily Democratic and the Democratic candidate wins by a large margin, all votes cast for that candidate above the 50-percent-plus-one threshold count as “wasted.” Conversely, all votes Republican voters cast for their losing candidate in that district would be “wasted.” The end result is that if a political party engages in conventional gerrymandering practices — “packing” and “cracking” the opposing party’s voters into and across districts39 — the line-drawing party will have fewer wasted votes than the other, as it will place more of its voters in competitive districts where they eke out narrow victories.

One of the virtues claimed by proponents of efficiency gap analysis is that it helps to demonstrate the magnitude and durability of partisan redistricting effects.41 As such, it may serve as useful circumstantial evidence of partisan intent.42 Various studies have considered a 7-8 percent efficiency gap as a threshold for a legally significant EG that is likely to “persist over the life of the plan.”43 The EGs for the Wisconsin plan at issue in Whitford were 13 percent and 10 percent for 2012 and 2014, respectively — “among the largest scores” for any state.

Plaintiffs in a challenge to New York’s state legislative lines could similarly point to a high efficiency gap to bolster their claims. We conducted an analysis of the EGs for New York’s state legislative districts in the 2012, 2014, and 2016 elections — every election using the current maps, which were drawn in 2012. For contested races, we calculated how many votes would be needed to garner a 50-percent-plus-one majority of the votes that went to the two major parties, and used that figure to calculate the “wasted” votes for each party. For uncontested races, we first imputed votes prior to the efficiency gap calculation. To do so, we calculated each major party’s average share of the vote total for its respective presidential candidate that cycle45 in each of three scenarios: when that party ran an incumbent for the state seat, when the opposing party ran an incumbent, and when neither party ran an incumbent. We then used those values to impute vote totals for each major party in an uncontested district by applying the relevant average share to the presidential vote total in that district.

Using this method, we found overall efficiency gaps (combining numbers for the state Senate and Assembly) of 11.51 percent in favor of Republicans in 2012, 11.64 percent in favor of Republicans in 2014, and 12.81 percent in favor of Republicans in 2016. In the Assembly, the EGs were 10.94 percent in favor of Republicans in 2012, 4.20 percent in favor of Republicans in 2014, and 10.47 percent in favor of Republicans in 2016. In the Senate, the EGs were 12.08 percent in favor of Republicans in 2012, 19.18 percent in favor of Republicans in 2014, and 15.17 percent in favor of Republicans in 2016.47

This is essentially consistent with the plaintiffs’ expert findings in Whitford, where Professor Simon Jackman calculated that New York’s median efficiency gap estimates were the most Republican-favoring out of any state over the period he surveyed, with pro-Republican efficiency gaps of 13 percent and 8 percent in 2012 and 2014, respectively.48 The differences between our calculations and Professor Jackman’s are likely attributable to differences in methodology in imputing vote totals for uncontested races.49 By either estimation, the Republican-favoring efficiency gap in New York is on average beyond the 7-8 percent threshold for legal significance suggested by the plaintiffs in Whitford and by Professors Stephanopoulos and McGhee.50 If this gap persists, efficiency gap analysis may therefore help to bolster a constitutional challenge to future New York lines.

If such analysis plays a role in a New York redistricting challenge, defenders of the district lines would likely argue that these numbers are inconsistent with patterns of political control in the state legislature. While the EG certainly favors Republicans more strongly in the Senate, it still favors Republicans in the Assembly — which might be seen as a surprising outcome given Democrats’ longstanding control of the Assembly.

Defenders of the lines could argue, for example, that Republicans have a natural political geography advantage for the reasons discussed further in Section III.B. Plaintiffs bringing the challenge might contest this, however, by pointing to other explanations for why the Assembly has a pro-Republican efficiency gap. It could be argued, for example, that the Assembly is, historically, highly uncompetitive in favor of Democrats, such that Assembly Democrats have seen little need to compound their advantage by gerrymandering to place Republican candidates at a further disadvantage (except perhaps to help or hinder certain candidates rather than the party overall). Such a result would be compatible with both the pro-Republican EG in the Assembly and the more pronouncedly pro-Republican EG in the Senate, where Senate Republicans have more of an incentive to solidify their electoral standing given their slim majority.

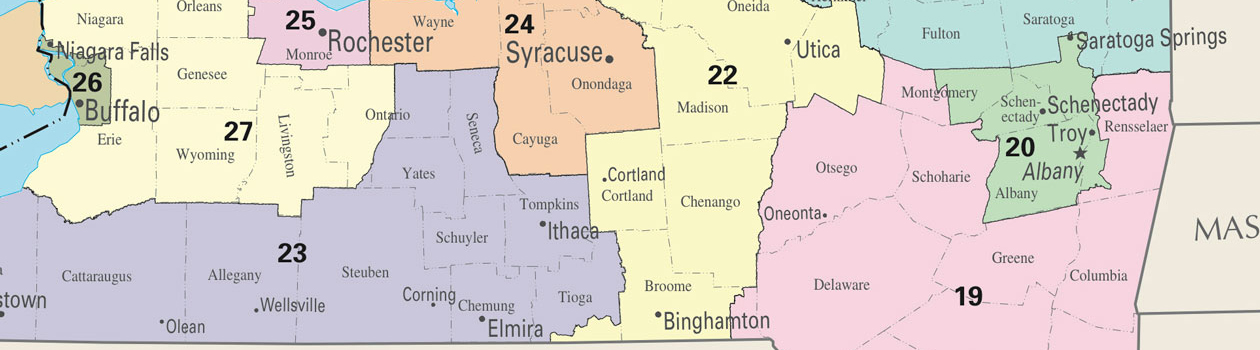

Plaintiffs could also argue that Senate Republicans benefited from adding a sixty-third district in a Republican-friendly upstate area prior to the 2012 elections,53 a strategy that Assembly Democrats are unable to pursue given the Assembly’s fixed number of seats. Whether these explanations ultimately would succeed depend on a deeper analysis of the facts underlying New York’s lines, and what evidence existed to demonstrate partisan intent. It is worth considering more broadly, however, what obstacles have existed to partisan gerrymandering challenges in New York — and whether the 2014 amendment alters the landscape surrounding those obstacles.

Regardless of how they seek to prove partisan intent in violation of the 2014 amendment, future challenges on those grounds must still address previous obstacles to New York partisan gerrymandering challenges. Specifically, courts will likely consider how redistricting challenges under this provision interact with previous case law on bipartisan gerrymandering, as well as how they interact with New York’s political geography.

As discussed supra, courts have typically treated “bipartisan gerrymanders” as inappropriate targets for partisan gerrymandering claims,54 and this has diminished the viability of multiple New York challenges.55 Once the redistricting commission goes into effect, it will seemingly present a clear example of a bipartisan redistricting effort. Moreover, even New York’s legislative redistricting efforts have typically involved input from both major parties, with a general aim of favoring incumbents.

Despite the prevalent role that bipartisanship has played in past New York challenges, a state constitutional challenge under the 2014 amendment may avoid the issue entirely. In addition to prohibiting genuinely partisan gerrymandering, the text of the amendment also expressly prohibits drawing districts “to discourage competition or for the purpose of favoring or disfavoring incumbents”57 — the hallmark of a bipartisan gerrymander, where the protections for incumbents and partisan control over one chamber may trump the potential for (and perceived value of) electoral competitiveness for the incumbents’ political party across the entire legislature.58 As such, it appears that one primary reason courts previously dismissed partisan gerrymandering challenges in New York may not serve as a defense to challenges under this amendment.

Prospective plaintiffs may have to contend more seriously with a political geography defense to a partisan gerrymandering challenge, even one brought under the 2014 amendment. New York features densely populated cities in addition to sparsely populated rural areas, and Democrats are often more densely concentrated than

Republicans due to a variety of factors.59 It will be argued that this makes it difficult for even the most well-meaning, neutral legislature to draw district lines that fulfill its other objectives — like compliance with federal and state redistricting requirements — without skewing the districts’ political balance. The Vieth Court recognized this as a potential issue, rejecting the plaintiffs’ standard in that case as nonjusticiable partly because, “[w]hether by reason of partisan districting or not, party constituents may always wind up ‘packed’ in some districts and ‘cracked’ throughout others.”60 If facets of political geography hinder a plaintiff’s ability to show that the districts actually discriminate against members of a political party, then this could threaten a state constitutional challenge.

There are, of course, ways plaintiffs could resist such a conclusion. In particular, the district court in Whitford endorsed a strategy for addressing political geography concerns that may prove generally useful to future challengers. The state in Whitford pointed to Wisconsin’s political geography as a justification for the plan it selected.

The court accepted that Wisconsin’s political geography gave Republicans “a modest natural advantage in districting,”62 but ultimately concluded that this “modest” advantage did not excuse the sizable partisan effect of the plan at issue. In doing so, the majority looked to the fact that the Wisconsin legislature considered and rejected otherwise comparable plans for partisan reasons,63 as well as the plaintiffs’ expert’s ability to draw a more neutral plan that still conformed to traditional legislative objectives.64 If plaintiffs in a New York challenge could make a similar showing, they might be successful in resisting the political geography defense.

If history is any guide, New York’s legislative district lines will end up in court after the 2020 redistricting cycle. This new constitutional “hook” and some of the recent approaches to identifying and proving partisan gerrymandering give new promise to potential challenges.