August 2017

Public pension funds invest in stocks, bonds, and other assets with the goal of accumulating sufficient funds, in combination with employer and employee contributions, to pay benefits when due. Investments can entail risk, and contributions may be increased (or decreased) to ensure that assets are sufficient to pay benefits.

When a pension fund invests in a portfolio of assets that entails higher risk, expected investment returns generally will be higher and contributions lower than for a portfolio of lower-risk assets. Expected returns, however, are not guaranteed returns, neither in the short or (even) long term.

In this report, we examine the potential implications of investment return volatility for the Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS). We selected PSERS as one of five plans to analyze in detail in our Public Pension Simulation Project. The five plans have a broad range of characteristics. PSERS is a deeply underfunded plan by public pension plan standards, with a market-value funded ratio of 50 percent at the end of the 2016 fiscal year. PSERS uses a relatively conservative amortization method to repay the unfunded liability, and has an uncommon approach to funding under which some employees, under some circumstances, share partially in the plan’s investment risk. A recently passed pension reform bill will introduce a defined contribution (DC) component to the traditional defined benefit (DB) plan in PSERS.

We draw several conclusions from our analysis:

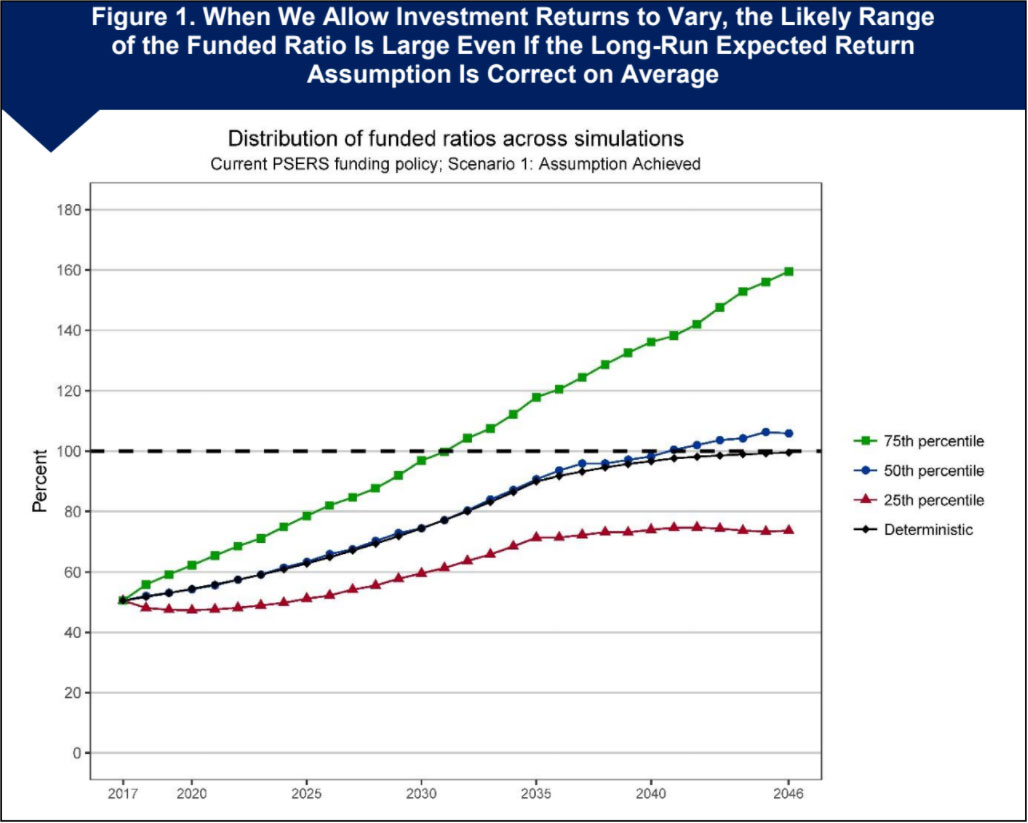

- There is a 26 percent chance that the funded ratio of PSERS will fall below 40 percent — what we consider to be crisis territory — sometime between now and year thirty.

- There is a 6.4 percent probability that employer contributions will increase by more than 10 percent of payroll within a consecutive five-year period sometime in the next thirty years. The low risk of sharp increases in employer contribution is partly attributable to PSERS’ relatively long ten-year asset smoothing period.

- The relatively conservative amortization method used by PSERS — twenty-four-year level-percent closed amortization — coupled with full payment of the actuarially determined contribution are crucial to ensuring the funding security of PSERS.

Our findings for PSERS illustrate the wide range of challenges and potential solutions that public pension funds and their governmental sponsors face. In contrast to other funds we have modeled (see www.rockinst.org/government_finance/pension.aspx for other pension reports), PSERS is deeply underfunded and faces greater challenges. The state’s recent move to pay full actuarially determined contributions, coupled with PSERS’ conservative funding policy, mean that PSERS is on a path to full funding within a little more than two decades, if the state continues to pay full contributions and if investment performance is about as good as the plan assumes. Contributions will be high over those two decades as the state pays down current unfunded liabilities. As with other plans we have modeled, contributions could rise or fall substantially depending upon investment performance. Unlike other plans we have modeled, contribution risks for employers will diminish over the long term as more workers participate in the recently enacted hybrid plans and thereby share a greater portion of the plan’s investment risk.

Public pension funds invest in stocks, bonds, and other assets with the goal of accumulating sufficient funds, in combination with employer and employee contributions, to pay benefits when due. Investments can entail risk, and contributions may be increased (or decreased) to ensure that assets are sufficient to pay benefits. When a pension fund invests in a portfolio of assets that entail higher risk, expected investment returns generally will be higher and contributions lower than for a portfolio of lower-risk assets. The disadvantage is that expected returns are not guaranteed returns, neither over short time periods nor even over the long run.

Depending on how volatile investment returns are, a plan’s funded ratio — the ratio of pension fund assets to pension fund liabilities — may rise or fall significantly, and required contributions may fall or rise considerably. The extent and timing of these changes will depend in part upon methods used to determine contributions. If adverse movements in investment returns are too large, funded ratios could become so low that they create political crises, which, in some states, may lead to pressure to cut benefits. Adverse movements could cause requested contributions to increase so much that they create fiscal stress for government employers, leading to pressure for substantial increases in taxes or other revenue, cuts in spending, or other undesirable outcomes. Alternatively, investment returns above expectations could lead to very high funded ratios and very low required contributions.

How much risk is too much risk? There is no magic rule, although academic research provides useful insights.1 Plans, employers, and other stakeholders need to weigh the potential risks and rewards. The key to making these decisions is to understand risks, evaluate risks, and communicate that analysis to those affected. In this report, we examine the potential implications of investment return volatility for the Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS). We selected PSERS as one of five representative plans to analyze in detail in our Public Pension Simulation Project. The five plans have a broad range of characteristics. PSERS is a deeply underfunded plan by public pension plan standards, with a market-value funded ratio of 50.0 percent at the end of the 2016 fiscal year. PSERS has an uncommon approach to funding under which some employees share partially in the plan’s investment risk, in certain circumstances. The other plans, which we examine in separate analyses, include a very well-funded plan, an average plan, a closed plan, and a public safety plan.

Risks can be positive or negative, and we examine both in this report. However, we pay particular attention to the consequences of investment return shortfalls because shortfalls can be extremely problematic for pension plans, beneficiaries, policymakers, and government stakeholders. To evaluate risks, we focus on risks to the plan measured by the market-value funded ratio, and risks to the employer measured by employer contributions as a percentage of payroll or budget. We examine the probability that the funded ratio or employer contributions may change considerably over time or enter into what we consider to be crisis territory. We analyze PSERS finances under the current funding policy and practice, as well as several alternatives, and we explore different investment return scenarios. We also examine the potential impact of introducing a defined contribution (DC) component into a traditional defined benefit (DB) plan, which we believe will provide useful insights for the recently enacted DB-DC hybrid plan reform in Pennsylvania.

The Public School Employees’ Retirement System of Pennsylvania (PSERS) is a defined benefit retirement plan for public school employees of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The state and individual school districts participate in PSERS. In addition to the pension plan, PSERS also provides voluntary post-employment health care benefits, which we exclude from our analysis — references to PSERS in this report pertain only to the pension plan.

As of June 30, 2016, PSERS had over 257,000 active members and approximately 225,000 retirees and other beneficiaries who receive over $476 million in pension and health care benefits each month. PSERS had $50.0 billion in assets. Its market-value-of-assets funded ratio was 50.0 percent — about the 25th percentile among large public pension plans.

Its unfunded liability based on market value of assets was $50.1 billion. Benefits generally are calculated based on the annual average of the highest three years of compensation. The normal retirement benefit equals 2.5 percent (for members hired before July 1, 2011) or 2 percent (for members hired on or after July 1, 2011) of the final average compensation multiplied by the member’s years of employment. The overall PSERS normal cost — the cost of benefit accruals attributed to each new year of service for covered employees — was 15.24 percent of total payroll in 2016.

On November 23, 2010, Governor Ed Rendell signed HB 2497 into law, which is now known as Act 120 of 2010. This Act preserves the benefits of existing members (Class T-C and Class T-D) and includes a series of actuarial and funding changes to PSERS and benefit reductions for individuals who become new members of PSERS after July 1, 2011, which are summarized below:

- Base employee contribution rates are 7.5 percent of payroll for Class T-E members and 10.3 percent for Class T-F members.

- Every three years the fund compares prior investment performance to assumed performance. If the investment rate of return (less investment fees) is 1.0 percent or more above the assumed rate of return based on the prior ten-year period, the member contribution rate for Class T-E and Class T-F will decrease by 0.5 percent. If the investment rate of return (less investment fees) during the prior ten-year period is 1.0 percent or more below the assumed rate of return, the member contribution rate will increase by 0.5 percent. The member contribution cannot fall 2 percentage points below the base rate, and cannot be raised more than 2 percentage points above the base rate. If the retirement system is fully funded and the shared-risk employee contribution rate is greater than the base rate at the time of the comparison, the member contribution rate reverts to the base rate.

- Act 120 mandated that the outstanding balance of the unfunded accrued liability as of June 30, 2010, including changes in the unfunded accrued liability due to the funding reforms of Act 120, be amortized over a twenty-four-year period as a level percent of pay, beginning July 1, 2011.

- To address the employer contribution rate spike caused by the amortization payments for the 2010 unfunded liability, Act 120 imposed lower and upper limits on the rate at which employer contributions may rise from year to year, known as “collars.” The employer contribution rate cannot increase by more than 4.5 percentage points of payroll relative to the prior year’s final contribution rate. If the actuarially determined contribution rate falls below the upper-limit rate, the final contribution rate is the actuarially determined contribution rate so long as it does not fall below the employer normal contribution rate.

In June 2017, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf signed into law Act 2017-5, which will change the retirement benefit structure available to new state employees. New members of PSERS hired on or after July 1, 2019, will be offered three options for retirement benefits: two hybrid benefit options that include a defined contribution (DC) component in addition to a defined benefit component, and a pure defined contribution option. This pension overhaul is intended to shift part of the funding risk, which is almost entirely borne by the state and school districts under the current pure DB plan structure (save for the shared-risk provisions, which have a relatively small impact as examined below), to new employees.

To fund the plan, the independent actuary determines a recommended employer contribution. This contribution is an actuarially determined amount calculated using the following method and funding policies:

The actuarially determined contribution is a recommended amount and the contribution actually paid could differ from it. During 2006 through 2010, the employer contribution as a percentage of the actuarially determined contribution ranged from 27 percent to 41 percent.

Starting from 2011, actual employer contributions have been capped by the Act 120 employer contribution growth collar. The actual employer contribution as a percentage of the actuarially determined contribution rose from 27 percent in 2011 to 69 percent in 2015. For fiscal year 2016-17, PSERS received 100 percent of actuarially required contributions for the first time in fifteen years. This marks a significant milestone in PSERS’ contribution history and establishes a path to full funding.

PSERS currently uses a 7.25 percent earnings assumption. As of June 30, 2016, approximately 21.8 percent of assets were in equity, 25.3 percent in collective trust funds, 8.4 in fixed income, and the remainder in other asset classes including real estate and private equity. As of June 30, 2016, the one-year, three-year, five-year, and ten-year annualized rates of return were 1.29 percent, 6.24 percent, 6.01 percent, and 4.94 percent, respectively.

We have developed a simulation model that can be used to evaluate the implications of investment risk to public pension funds. The model calculates the annual cash flows, fiscal position, and covered payroll of a public pension plan for future years. Typically, we run a simulation for fifty years or more but focus our analysis on the earlier years. Each year the model starts with beginning asset values and computes ending assets by subtracting benefits paid, adding employee and employer contributions (including any amortization), and adding investment income, which we calculate in the model.

The model keeps track of these values and other variables of interest, such as the funded ratio and employer contributions as a percentage of payroll. It saves all results so that they can be analyzed after a simulation run in any way desired.

Investment returns in this model are determined flexibly, and can be:

When investment returns for a scenario have a stochastic component we run 2,000 simulations, each with a different set of annual investment returns (drawn from the same assumed probability distribution), so that we can examine the distribution of results. (See the Appendix, “Illustration of Possible Investment Returns in a Stochastic Scenario” for an example.) Each simulation results in different investment earnings, leading to different funded ratios and contribution requirements. By examining the 2,000 different sets of results we can gain insight into the probability of alternative outcomes. (See the box, “Deterministic Versus Stochastic Models” for a more detailed discussion on the advantages of the stochastic approach.) For example, we examine the probability that the funded ratio will fall below 40 percent anytime during the first thirty years — a level that has been associated with crisis in other states.

We use our pension simulation model to generate projections of covered payroll, annual benefit payments, and actuarial liabilities of PSERS. We assume that enough new employees are hired each year to keep the size of the covered workforce constant over time.7 Actuarial liabilities, annual benefits, and payroll vary from year to year, but do not vary across simulations in a single scenario. These projections are based on the demographic data, decrement tables, benefit provisions, and actuarial assumptions provided in the PSERS actuarial valuation report of 2016. The projections do not incorporate the hybrid DB-DC plans established by Act 2017-5, but they do include the Act’s modifications to the shared-risk employee contribution rates (see the descriptions under “Funding Approach” above). We analyze the impact of introducing a DC component into a DB plan separately below (see “How Would Transitioning to a DB-DC Hybrid Pension Plan Affect the Funding Risks of PSERS?”).

Employer contributions are determined as follows:

To summarize, the employer contribution is designed to fill the gap between the employee contribution and an actuarially determined total contribution, except that (a) it cannot be negative, (b) it must be at least as great as the employer normal cost (total normal cost minus employee contribution), and (c) it cannot grow by more than 4.5 percentage points of payroll from one year to the next.

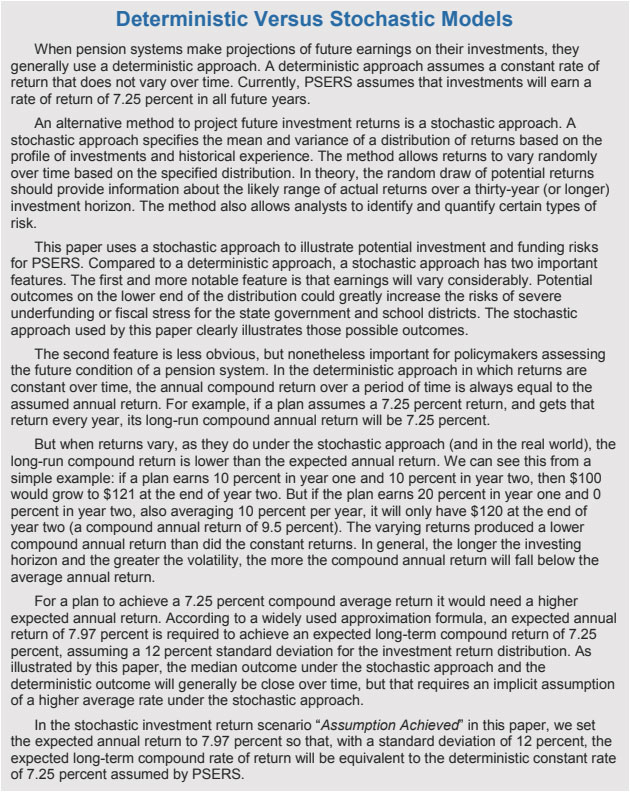

Table 1 shows these three simulation scenarios. The first two columns label and describe the simulation. Columns three and four show the expected compound return during subperiods of the first thirty years. The fifth column shows the expected compound return over the full thirty years and the sixth column shows the standard deviation.

Although we extend our model for fifty years, we generally focus on the first thirty years, in the belief that this is a meaningful period for policymakers.12 We organize our discussion of results as follows:

Before the discussion of simulation results, we first describe the measures we use to quantify funding risks caused by investment return volatility.

We are primarily concerned about two kinds of risks:

There usually are trade-offs between these two kinds of risks and how the trade-offs operate is a function of a plan’s contribution policy. If a pension plan has a contribution policy designed to pay down unfunded liabilities very quickly, it is unlikely to have low funded ratios but it may have high contributions. If a pension plan has a contribution policy designed to keep contributions stable and low, there is greater risk that funded ratios may become very low because contributions may not increase rapidly in response to adverse experience.

We use several measures to evaluate these risks. We describe the two most useful measures below.

When returns are stochastic, many outcomes are possible, including extreme outcomes, so it does not make sense to focus on the worst outcomes or the best outcomes. We are particularly concerned about the risk of bad outcomes, and one useful measure is the probability that the funded ratio, using the market value of assets, will fall below 40 percent in a given time period.

We choose 40 percent because it is a good indicator of a deeply troubled pension fund. In 2013, only four plans out of 150 in the Public Plans Database14 had a funded ratio below 40 percent — the Chicago Municipal Employees and Chicago Police plans, the Illinois State Employees Retirement System, and the Kentucky Employees Retirement System. Each plan is widely recognized as being seriously underfunded, with the likelihood of either substantial tax increases, service cuts, or benefit cuts yet to come.

Making contributions stable and predictable is one of the most important goals of funding policies from the perspective of the employer. Sharp increases in employer contributions, even if not large enough to threaten affordability, can cause trouble in budget planning. We use the probability that the employer contribution will rise by more than 10 percentage points of payroll in a five-year period to measure this possibility. Extremely low returns in a very short time period, as may occur in a severe financial crisis, may push up the required contribution considerably even after being dampened by asset smoothing and amortization policies.

In Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” the expected long-run compound return is 7.25 percent, and returns vary from year to year with a standard deviation of 12 percent.

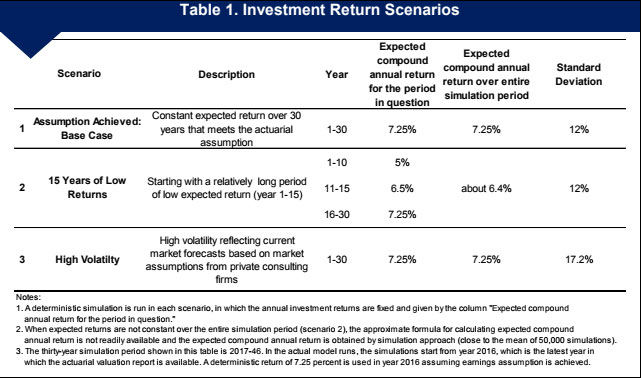

We first show the likely range of funded ratios resulting from the 2,000 simulations under Scenario 1. Figure 1 shows the median funded ratio, the 25th percentile, and the 75th percentile, along with the funded ratio in the deterministic version of Scenario 1, in which the investment return is 7.25 percent every year. The initial funded ratio is 50.0 percent. In the deterministic run, because there are never any investment shortfalls or overages, the plan marches closer to full funding every year.

In the stochastic scenario, investment returns in any single year will be better or worse than assumed. In some simulations, returns may be worse than assumed for many years in a row. Although contribution policy is intended to put the plan back on a path toward full funding after investment shortfalls, the combination of asset smoothing, a long amortization period, and a series of bad investment returns can lead to circumstances where plan funding becomes dangerously low. By the same token, the plan can become considerably over-funded after experiencing a series of good investment returns.

Figure 1 shows that if the expected long-term compound return is equal to the assumed return of 7.25 percent during the next thirty years, in 25 percent of the simulations with relatively bad investment returns, those at the 25th percentile line or lower, the funded ratio, starting from about 50 percent in 2017, will become 74 percent or lower by 2046, while in another 25 percent of simulations with relatively good investment returns, those at the 75th percentile line or higher, the funded ratio will rise to 160 percent or higher. In the other 50 percent of simulations, the funded ratio in 2046 will fall between these values.15 Improvements in the funded ratio can be partly attributed to PSERS’ relatively conservative amortization policy (twenty-four-year level percent closed amortization) for unfunded liabilities. Under a hypothetical scenario in which PSERS would use open amortization with a twenty-four-year amortization period, the median funded ratio would only rise to 67 percent after thirty years, and the 25th percentile funded ratio would fall to 45 percent.

Figure 2 shows the risk of a dangerously low funded ratio under the stochastic scenario. At each year, the graph shows the probability that the funded ratio, based on the market value of assets, will have fallen below 40 percent in any year up to that point. Under Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” thirty years into the simulation (2046) there is a 26 percent chance that the funded ratio will have fallen below 40 percent at some point in the period. Although a 26 percent chance of becoming severely underfunded under the current funding policy is by no means low, the risk could be even higher if PSERS used a less conservative amortization method. Under the hypothetical scenario in which PSERS would use twenty-four-year open amortization, the probability that the funded ratio will fall below 40 percent at some point in the next thirty years would be 47.5 percent.

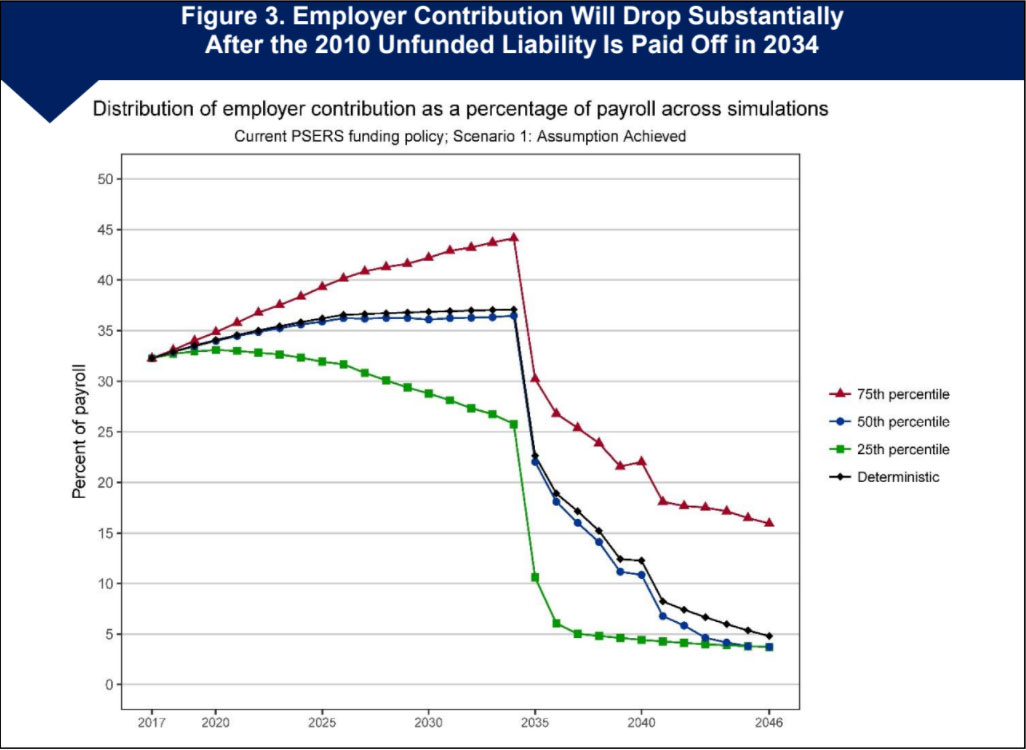

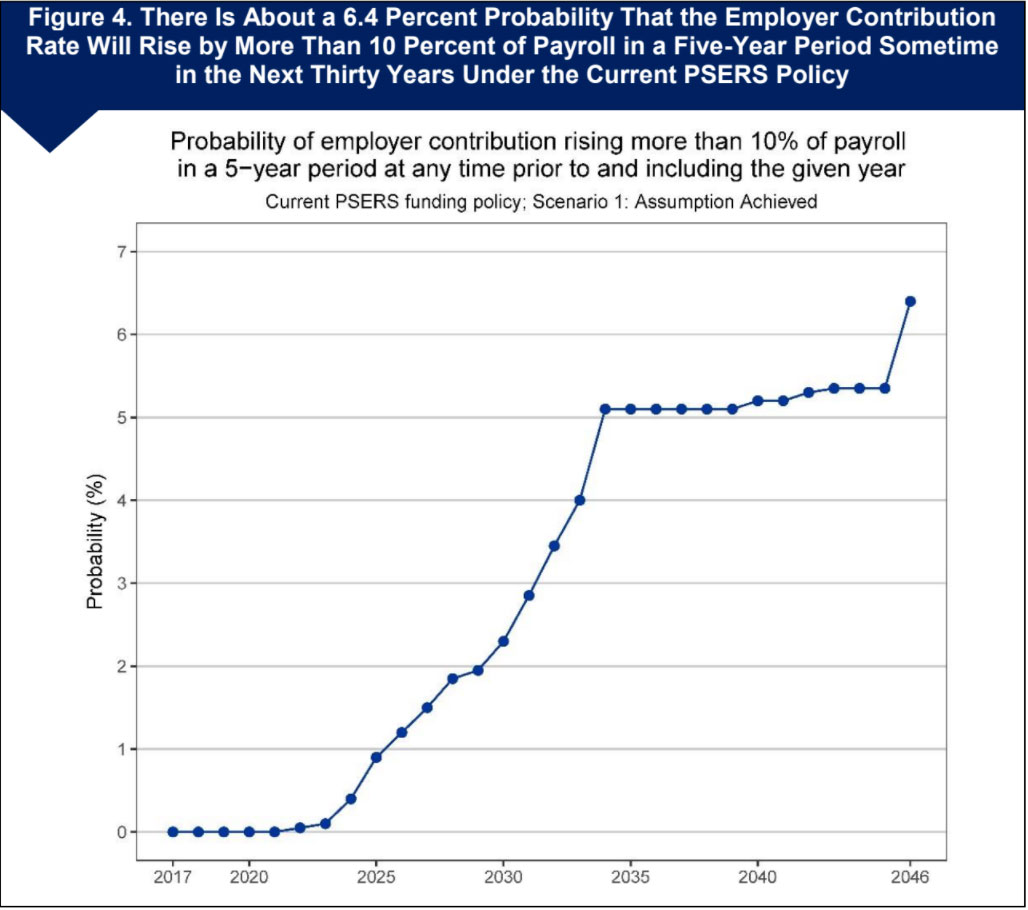

The amortization payments for the outstanding balance of the 2010 unfunded liability will account for a significant proportion of the total employer contribution to PSERS in the next twenty years. After the 2010 unfunded liability is paid off, the employer contribution rate will drop significantly. Under Scenario 1 “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” where investment returns vary from year to year, there is a 6.4 percent chance that the employer contribution rate will rise by more than 10 percent of payroll within at least one five-year period sometime in the next thirty years. The sharp increases in the employer contribution rate are mostly to occur in the next twenty years when PSERS is paying down the 2010 unfunded liability.

Figure 3 shows the median employer contribution as a percentage of payroll under the stochastic scenario, along with the 25th percentile and 75th percentile, and the employer contribution rates under the deterministic version of Scenario 1. The median employer contribution rate, starting at around 32 percent in 2017, gradually increases to about 36 percent in the next twenty years, and then drops drastically after the 2010 unfunded liability is paid off, reaching around 4 percent of payroll in 2046.16 The 25th percentile for employer contribution rates, which represents simulations with relatively good investment returns, falls to about 25 percent in twenty years, then drops further to about 4 percent in 2046. In a quarter of the simulations that have relatively bad investment returns, those at the 75th percentile line or above, the employer contribution will rise to 44 percent in the next twenty years and will be still around 16 percent after a significant drop.

Figure 4 shows the risk of large increases in employer contributions in a short time. Each point shows the probability that the employer contribution rose by more than 10 percent of payroll in any previous consecutive five-year period. For example, the probability at 2030 is about 2 percent. This means that there is about a 2 percent chance that employer contribution rate will have increased by more than 10 percentage points in any previous consecutive five-year period, such as periods from 2020 to 2025, 2021 to 2026, and so on, through 2025 to 2030. By the end of the thirty-year period, there is about a 6.4 percent chance that contributions will have increased by more than 10 points in at least one of those five-year periods. The relatively flat curve after 2034 implies that most of the sharp increases in employer contribution will occur during 2017 to 2034. In the period from 2035 to 2045, as the amortization basis established before 2017 is paid off, the amortization payments will decrease so significantly that the total employer contribution rate is unlikely to rise sharply as a percentage of payroll, even if large investment shortfalls occur. By 2046, the pre-2017 unfunded liability has been fully paid off for five years and base employer contributions have been low for five years, so the risk that contributions can rise from this new lower base once again climbs.

The ten-year asset smoothing in the current PSERS funding policy plays a very important role in preventing the employer contribution from increasing sharply in a short time period. Under Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” shortening the asset-smoothing period from ten years to five years would increase the probability of sharp increases in the employer contribution rate from 6.4 percent to 30.2 percent, while it will also slightly reduce the risk of severe underfunding (26 percent to 23.4 percent). While the long asset-smoothing period does not have a substantial impact on the risk of severe underfunding, it may have other impacts. By insulating current policymakers from the consequences of investment shortfalls, it may encourage investment risk taking that could create a very difficult situation for the fund if investment markets take a sharp drop.

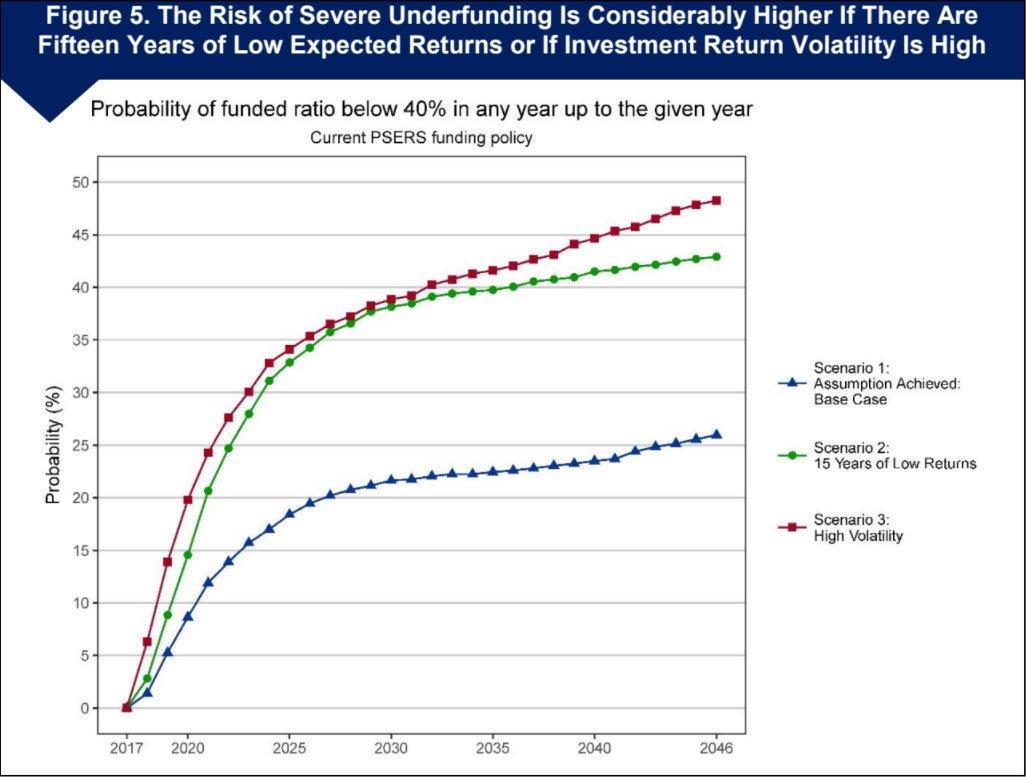

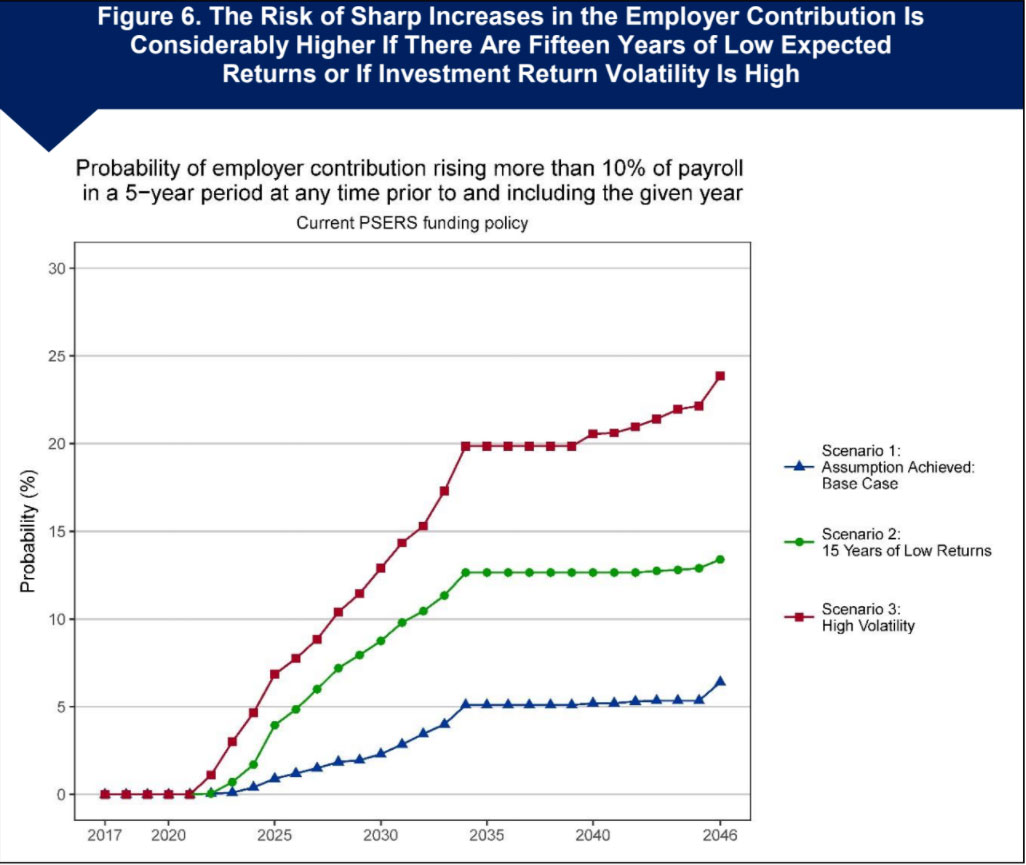

In this section we compare Scenario 2: “15 Years of Low Returns” and Scenario 3: “High Volatility” to Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” in which the expected return is 7.25 percent and the standard deviation is 12 percent. Refer back to Table 1 for details of the investment return scenarios. The simulation results show that fifteen years of low returns and high investment return volatility will substantially increase the risk of severe underfunding and sharp increases in the employer contribution rate over the next thirty years.

If the true expected compound return is lower than the assumed return of 7.25 percent in early years, or if investment return volatility is higher than in the base case, the risk of severe underfunding will be much higher for PSERS than in the base-case scenario. Figure 5 shows the probability of the funded ratio falling below 40 percent under the three return scenarios. Under Scenario 2: “15 Years of Low Returns” and Scenario 3: “High Volatility,” the chances that the funded ratio will fall below what we consider a crisis level — 40 percent — sometime during the next thirty years are about 43 percent and 48 percent, respectively, which are considerably higher than the 26 percent probability under the base-case Scenario 1. Thus, in either of these investment return environments, PSERS could face very substantial risks of a crisis.

Low expected returns in early years and higher investment return volatility both create much higher risk of sharp increases in employer contributions. Figure 6 shows the probability of the employer contribution rising by more than 10 percent of payroll in a five-year period during thirty years. This probability increases from about 6.4 percent in the base-case Scenario 1, to 13.4 percent in Scenario 2: “15 Years of Low Returns,” and to 23.9 percent in Scenario 3: “High Volatility.”

The constraint on the employer contribution rate that limits the annual growth of the final employer contribution rate to 4.5 percentage points of payroll is rarely triggered in all three investment return scenarios we examined in the previous section, and it therefore is likely to have almost no impact on the finances of PSERS in the next thirty years under these scenarios. Under Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” the employer-contribution-rate constraint is triggered in only six out of the total of 2,000 simulations; even under Scenario 3 where investment returns are much more volatile, the number of simulations where the constraint is triggered is only 113. This result is not surprising since the 4.5 percent constraint was designed to phase in the steep increases in employer contribution caused by amortizing the entire 2010 unfunded liability, and investment shortfalls can rarely cause such a big single-year increase in the employer contribution rate under the current funding policy with ten-year asset smoothing.

The shared-risk mechanism allows the employee contribution rate to range from 5.5 to 9.5 percent for Class T-E members and from 8.3 to 12.3 percent for Class T-F members, depending upon a comparison between the ten-year average investment return and the plan’s assumption. This sharing has a relatively small effect on the stability of employer contribution rates.

Figure 7 compares the risk of sharp increases in the employer contribution rate under the current PSERS funding policy and under the same policy with the shared-risk employee contribution removed. Without the shared-risk employee contribution, the probability that the employer contribution will rise by more than 10 percent of payroll in five years sometime in the next thirty years is higher by 2 percent, 4.9 percent, and 3.2 percent under Scenario 1, Scenario 2, and Scenario 3, respectively. We also calculated the difference in the present value of employer contributions in the next thirty years in each simulation under the policy with and without the shared-risk mechanism. Under Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved: Base Case,” the shared-risk mechanism would reduce the employer contribution by 2.6 percent in the median case; in the 75th percentile case where the investment returns are relatively bad, the reduction in employer contribution is 5.6 percent.

The shared-risk employee contribution rate may have a small effect on the employer contribution because it exposes employees to little risk from poor investment returns: 1) the 2 percent floating range for the employee contribution rate is small; 2) the employee contribution rate is adjusted only every three years so that changes in the average investment return may not be reflected in a timely manner; 3) the adjustment is based on the ten-year average return, which is relatively stable; and 4) the asymmetric adjustment rule makes it more likely that the employee contribution will decrease rather than increase.

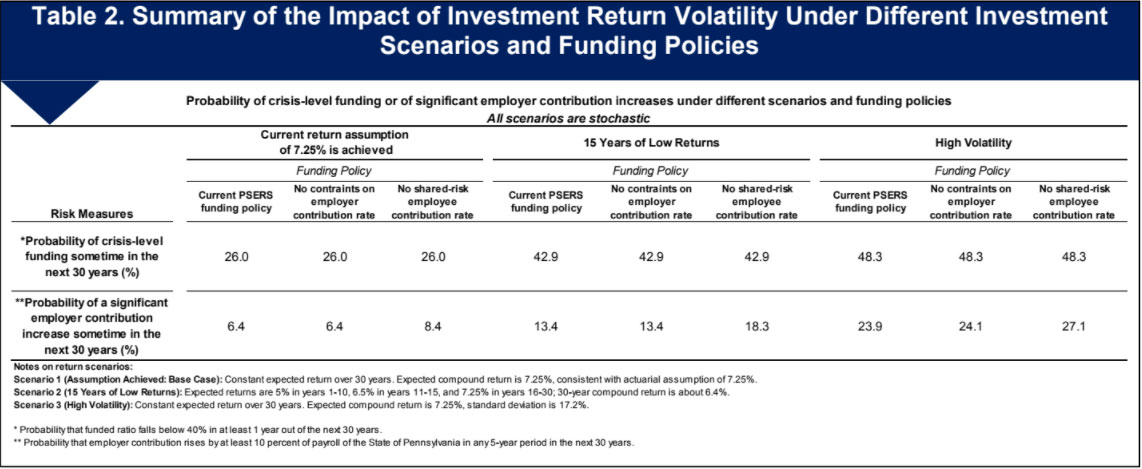

Table 2 summarizes the results of three investment return scenarios — the current PSERS funding policy, an alternative policy with the constraint on employer contribution growth removed, and another alternative in which the shared-risk employee contribution is removed. The next three columns show the results for Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved” under the three different funding policies. The next five columns do the same for Scenario 2: “15-Years of Low Returns,” and the final five columns are for Scenario 3: “High Volatility.”

The table shows that a period of low returns (Scenario 2) and a period of high investment return volatility (Scenario 3) create significant risks of severe underfunding and sharp increases in employer contributions. In all three investment return scenarios, the constraint on the growth of the employer contribution is rarely triggered and therefore has almost no impact on the funding and contribution risks of PSERS. This result is largely attributable to the ten-year asset smoothing period in the current PSERS funding policy, the effect of which is strong enough to make the employer contribution relatively stable from year to year and therefore makes the constraint on the employer contribution rate redundant.

The shared-risk employee contribution rate has a moderate impact on the contribution risk of PSERS. Removing the shared-risk mechanism would increase the chance of sharp increases in employer contribution in the next thirty years by 2.0 to 4.9 percentage points, depending on the investment return scenario.

In this section, we examine the potential fiscal pressure that PSERS may create for the state government of Pennsylvania. We use state employer contributions as a percentage of the Pennsylvania general fund as a measure of fiscal pressure. (We assume that state contributions are 50 percent of total employer contributions, based on the approximate split of state and school district contributions.) To calculate our fiscal pressure measure, we need forecasts of employer pension contributions, which come from our simulation model, and forecasts of the state’s general fund revenue, which we describe below.

We constructed a thirty-year projection of Pennsylvania’s general fund revenue as follows:

The resulting revenue projections are shown in Figure 11 in the Appendix.

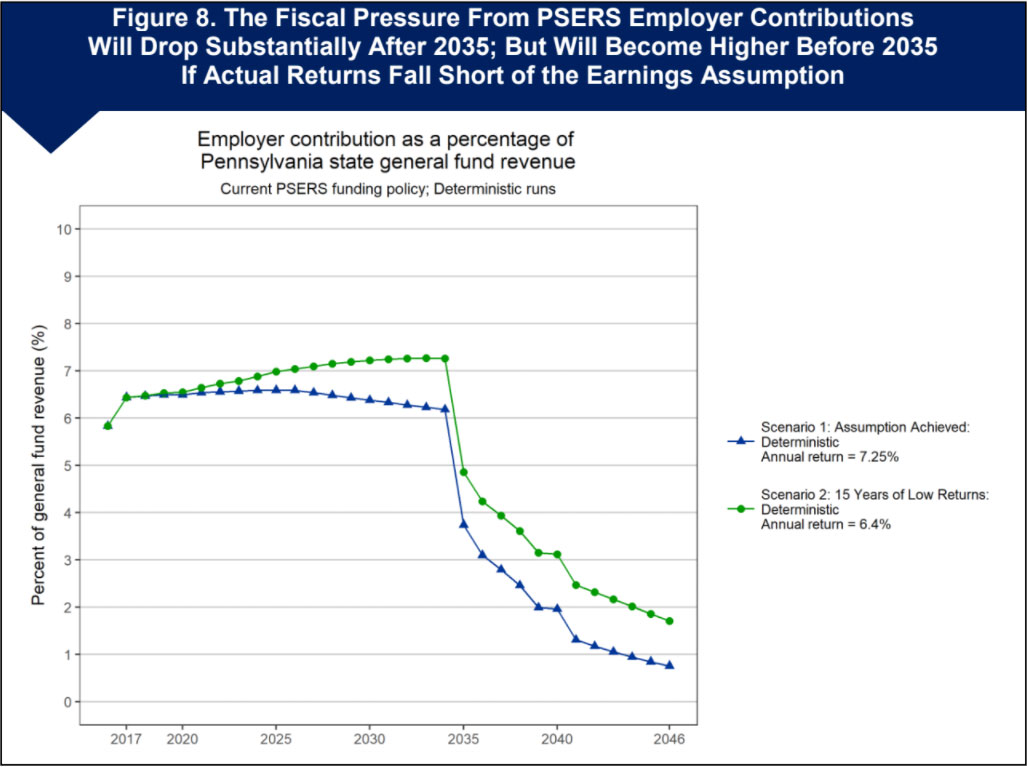

We first examine the fiscal pressure that PSERS pension contributions could create under scenarios with deterministic investment returns. Figure 8 shows employer contributions to PSERS paid by the state government, which is 50 percent of the total employer contribution, as a percentage of general fund revenue during the next thirty years under two deterministic simulations with different annual investment returns, labeled Scenarios 1 and 2. As before, Scenario 1 is the base case, in which PSERS’ assumption of a 7.25 percent return is achieved each and every year. Scenario 2 has fifteen years of low returns before returns rise, as described earlier.

Under the deterministic run of Scenario 1: “Assumption Achieved” in which the earnings assumption of 7.25 percent is met each and every year, government contributions as a percentage of general fund revenue will stay relatively stable, around 6 to 6.5 percent in the next twenty years. After the 2010 unfunded liability is paid off in 2035, the government contribution to PSERS will decline considerably from about 6 percent of general fund revenue to less than 1 percent by 2046.

The fiscal pressure from PSERS pension contributions is sensitive to realized investment returns. In the deterministic run of Scenario 2, which has returns lower than the assumed rate of 7.25 percent in the first fifteen years, the government contribution to PSERS rises to 7.3 percent of the general fund in 2034, and then declines to 1.7 percent in 2046 as the 2010 unfunded liability is paid off and investment returns rise back to 7.25 percent.

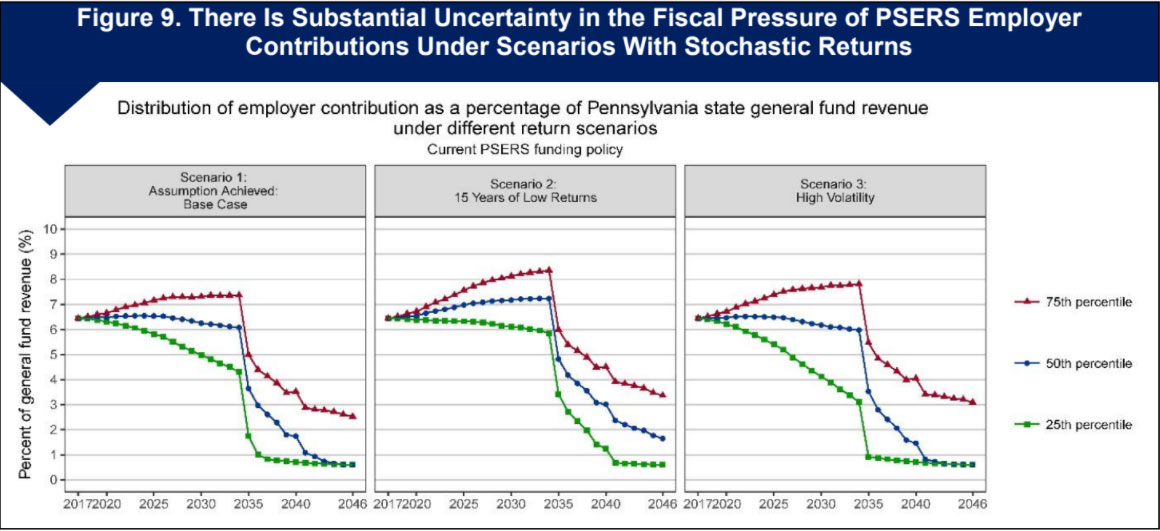

In scenarios with stochastic investment returns, the Pennsylvania state budget faces uncertainty from fiscal pressure related to PSERS employer contributions. Figure 9 shows the distribution of government contributions as a percentage of general fund revenue under the same three investment return scenarios as before. Under the base case Scenario 1 with an expected compound return of 7.25 percent and standard deviation of 12 percent (leftmost panel), although the median government employer contribution as a percentage of general fund revenue (blue line) stays around 6 to 6.5 percent through the next twenty years and drops to less than 1 percent after thirty years, in one quarter of the simulations the share of PSERS employer contributions will become 7.4 percent or higher in 2034 and 2.5 percent or higher in 2046 (see the 75th percentile represented by the red line).21 The 25th percentile line (green line), which represents the share of PSERS employer contributions in simulations with relatively good investment returns, drops to about 4 percent in the next twenty years and drops further to less than 1 percent by 2046. The risks of increases in the fiscal pressure of PSERS employer contributions are higher in scenarios with a period of low returns or greater volatility. The 75th percentile government employer contribution in 2034 is about 8.3 percent of projected general fund revenue under Scenario 2: “15 Years of Low Returns” (red line in middle panel), and about 7.8 percent of projected general fund revenue under Scenario 3: “High Volatility” (red line in rightmost panel).

The results above show that there is still great uncertainty in the fiscal pressure from the PSERS employer contribution before 2035. If returns are relatively bad (represented by the 75th percentile lines), the government employer contribution can rise 7.8 percent to 8.3 percent of projected Pennsylvania general fund revenue, or more, from about 6.4 percent in 2017.

The potential impact of introducing a hybrid component into PSERS has been examined in studies by the Pennsylvania Independent Fiscal Office and by The Pew Charitable Trusts.22 Our analysis differs from the previous studies in important ways. First, our goal is to draw general conclusions about the potential impact of introducing a hybrid benefit structure into a traditional DB plan, rather than to estimate fiscal effects for Pennsylvania. Thus, we do not attempt to model the new pension reform bill in all of its detail. Instead, we examine a simplified version that allows us to better isolate the impact of the hybrid plan. But the simplified reform is similar enough to the actual reform in Pennsylvania that we believe it provides useful insights for Pennsylvania. Second, in addition to showing results based on deterministic simulations in which investment returns are constant over time, we use our stochastic simulation model to show how a hybrid plan could affect risks caused by variation in investment returns.

We perform simulations to answer the following questions:

We constructed a simplified version of the recent Pennsylvania pension reform, in which the following DB-DC hybrid benefit structure is available to new participants of PSERS in our model:

We first examine the extent to which introducing our simplified DB-DC hybrid benefit structure would reduce contribution risk for the employer. In Pennsylvania, and in almost any state that adopts a hybrid plan, the new plan will affect only new employees. Regardless of how large or small the impact is for an individual employee, the impact in the early years will be small relative to the size of the plan as a whole and relative to the state budget, but the impact will grow over time as more and more employees are affected. (See the Appendix, “How the Share of the Hybrid Plan in PSERS Would Grow Over Time.”) To gain insight into the eventual fully effective impact, we begin by looking at new employees only. Next, we examine what would happen if the hybrid were fully in effect by treating it as if it applied to all current and future employees (see the appendix for modeling details). Finally, we examine how the reform would affect risk as it phases in over time.

Because the DB benefit in our simulated hybrid plan is only one half that of the current pure DB plan, its actuarial liability and associated assets will be only half as large (at the same funded ratio). As a result, when investment returns fall short, the DB component of the hybrid plan will generate smaller unfunded liabilities and amortization costs than the pure DB plan, and swings in employer costs will be only half as large as those for the pure DB plan, in dollar terms and as a percentage of the state budget. We examine the risk-reduction effect of the hybrid plan using both deterministic and stochastic simulation approaches:

We define employer pension costs to include the total employer contribution during the simulation period plus any unfunded liabilities remaining in the last simulation year, as these must eventually be paid by the employer. Nominal values of future costs, rather than present values, are used in the calculation of total employer pension costs.

To examine how much the hybrid plan would reduce risk for employers, we proceed as follows:

(Cost of DB at 6.25% — Cost of DB at 7.25%)

minus

(Cost of hybrid at 6.25% — Cost of hybrid at 7.25%)

The total employer pension cost includes the total employer contribution over the simulation period of 2017 to 2048 plus the unfunded liability remaining in the last simulation year.

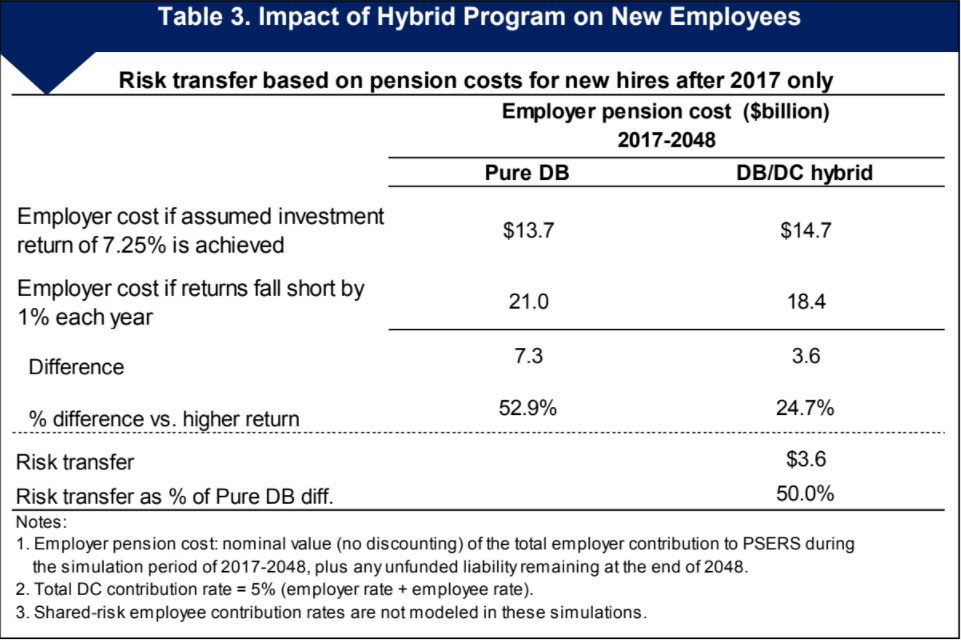

Table 3 shows the impact over thirty years of the hybrid program compared to the current pure DB program, focusing only on newly hired employees. Under the pure DB program, if investment returns fall short of assumed returns by 1 percentage point in every year, employer costs over thirty years will be $7.3 billion higher than if the return assumption is achieved. By contrast, if the hybrid program is in effect for new employees and actual investment returns fall short of assumed returns on a sustained basis, employer costs will be $3.6 billion higher than if assumed returns are achieved. Thus the employer cost will be reduced by 50 percent25 and the new employees will bear the rest of the risk. While the reduction in risk is relatively small in dollar terms because so few employees are affected, it is a large percentage reduction in risk for the employer.

The 50 percent reduction in employer risk reflects the fact that, for future employees, the DB component of the hybrid plan is half the size of the pure DB plan. We have verified with our simulation model that the risk transfer for the plan members affected by the hybrid plan reform is proportional to the reduction in their DB benefit compared to the original pure DB plan.26 This relationship between the risk reduction from a hybrid plan reform and the benefit reduction in the DB component of the hybrid can be generalized beyond PSERS.

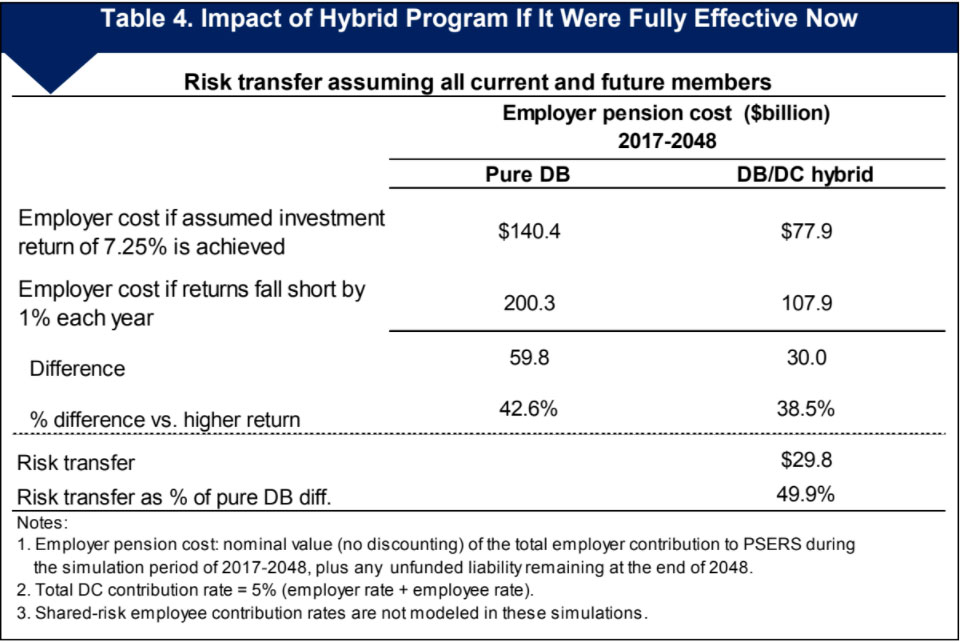

Table 4 shows the impact of the hybrid program as if it were in full effect now and applied to all current and future employees. Under the pure DB program, if investment returns fall short of assumed returns by 1 percentage point in every year, total employer costs over thirty years for current and new employees would be $59.8 billion higher than if the return assumption is achieved. By contrast, if the hybrid program were in effect for all current and new employees and actual investment returns fall short of assumed returns on a sustained basis, employer costs would be $30 billion higher than if assumed returns are achieved. The employer cost will be reduced by $29.8 billion, or nearly 50 percent.

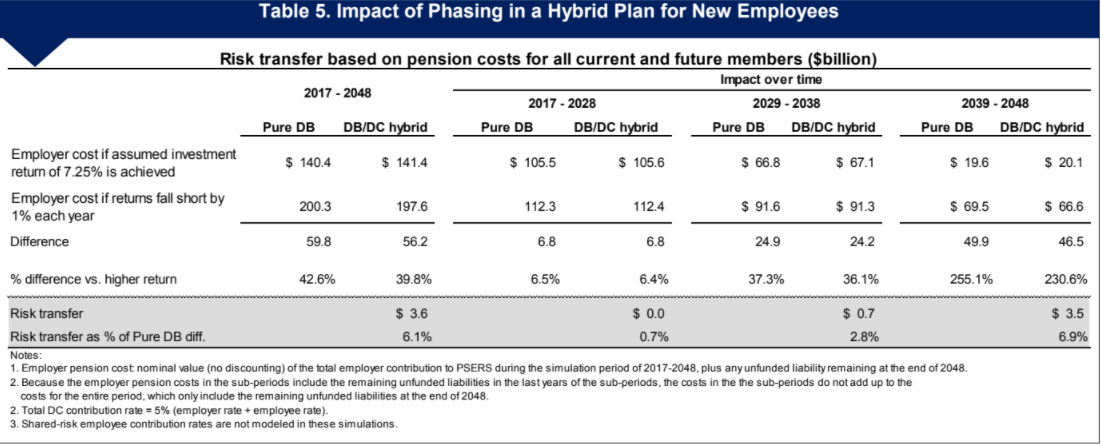

Pennsylvania and other states generally do not have the ability to move current employees into hybrid plans. Programs generally apply to new employees only. Thus, the risk reduction shown above will not be achieved right away. Table 5 shows the impact of phasing in a hybrid plan for new employees. The hybrid plan applies only to new hires, but the table shows employer costs for all employees to provide insight into the magnitude of savings relative to total costs. The table shows the risk-transfer measures broken down into three time periods: 2017-28, 2029-38, and 2039-48.

For the entire simulation period, if annual investment returns fall 1 percentage point short of the assumed 7.25 percent investment return in all years, the total employer pension cost for all current members and new hires (leftmost panel) is $59.8 billion (42.6 percent) higher under the pure DB plan than if assumptions are achieved. Under the DB-DC hybrid plan the total employer pension cost is $56.2 billion (39.8 percent) higher. The difference between these cost increases shows that the employer risk reduction under the hybrid plan is $3.6 billion, or 6.1 percent of costs that would be paid under the pure DB plan. (This is the same as the risk reduction shown in Table 3, where we focused solely on new employees.) The majority of the risk transfer occurs in the last ten-year period (last panel), when the number of hybrid plan members as a share of total employees is largest.

The risk transfer in the first two periods is minimal. The risk transfer will be small relative to the total pension costs in the next thirty years because it takes a long time for the hybrid plan to expand and the liability of the hybrid plan will only account for a relatively small share of the total liability of PSERS in the next thirty years.

For each randomly generated return series for the simulation period of 2017-48, the corresponding employer pension costs can be calculated. We run 2,000 stochastic simulations and compute the employer pension cost for each. The dispersion of the resulting distribution of employer pension costs reflects the uncertainty in pension costs when returns are stochastic.

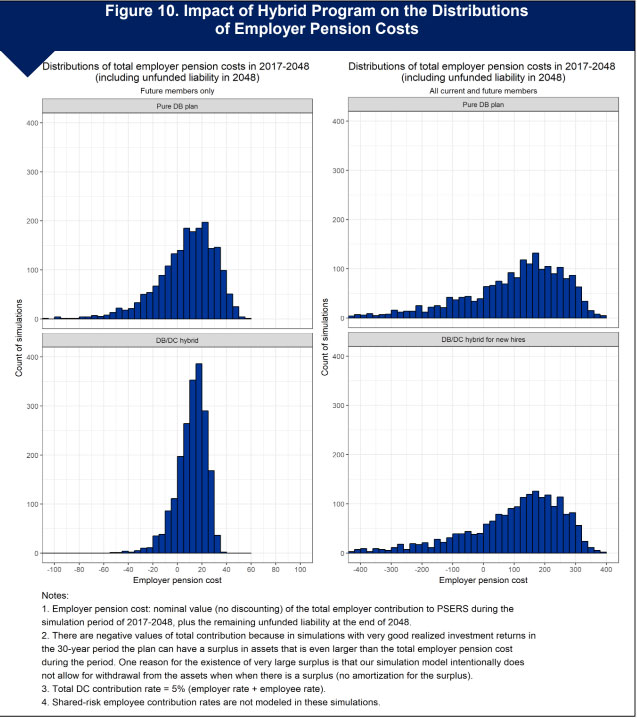

Under the stochastic approach, we define risk transfer as the reduction of uncertainty in employer pension costs when the hybrid plan is introduced to PSERS. Because the DB component is relatively smaller under a hybrid plan, the assets for which the employer bears investment risk are smaller, and the amount by which employer costs will vary in response to investment return variation also is smaller. Figure 10 compares the distributions of employer pension costs under the pure DB plan and the hybrid plan. In these simulations, investment returns are drawn from a normal distribution with a long-term expected compound return of 7.25 percent and standard deviation of 12 percent. The left panel shows the distribution of employer pension costs for new hires when they all participate in the current DB plan (top graph), compared with employer costs when members are in the hybrid plan (bottom graph). Employer costs are substantially less dispersed under the hybrid plan than under the pure DB plan. The right panel shows the distribution of total employer pension costs for all current and future members, when new hires participate in the current pure DB plan (top graph) and alternatively when all new hires participate in the hybrid plan (bottom graph). The two distributions are quite similar, which is consistent with the result of the deterministic simulation in which the risk transfer is quite small relative to the total pension costs for current and future members.

To quantify the reduction of uncertainty in pension costs under the stochastic simulation approach, we defined the stochastic risk transfer measure as follows:

(75th percentile cost of pure DB – 25th percentile cost of pure DB)

minus

(75th percentile cost of hybrid – 25th percentile cost of hybrid)

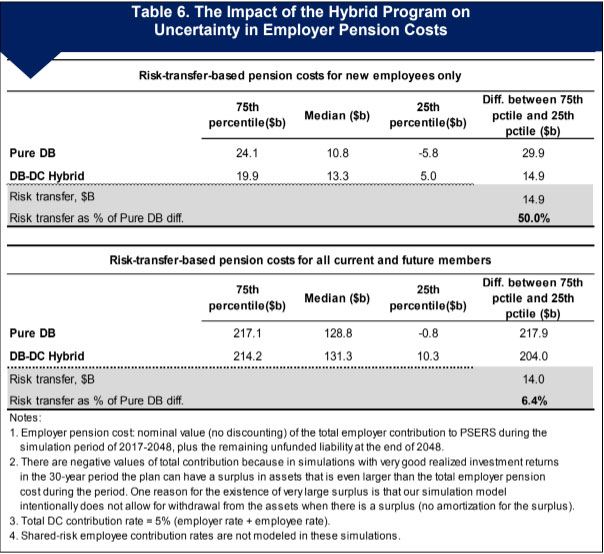

Table 6 shows the computed risk-transfer measure based on all current and future members (lower panel) and based on future members only (upper panel). As expected, the risk transfer is relatively small (6.4 percent) based on the total cost of all current and future members, and the risk transfer for future members is 50 percent.

The reduced risk in employer pension costs is transferred to employees in the form of uncertainty in retirement benefits: unexpectedly good investment returns in their defined contribution accounts would lead to higher assets at retirement and greater income in retirement, and unexpectedly bad returns would lead to lower income in retirement. In this section we estimate the benefit risk borne by the hybrid plan participants.

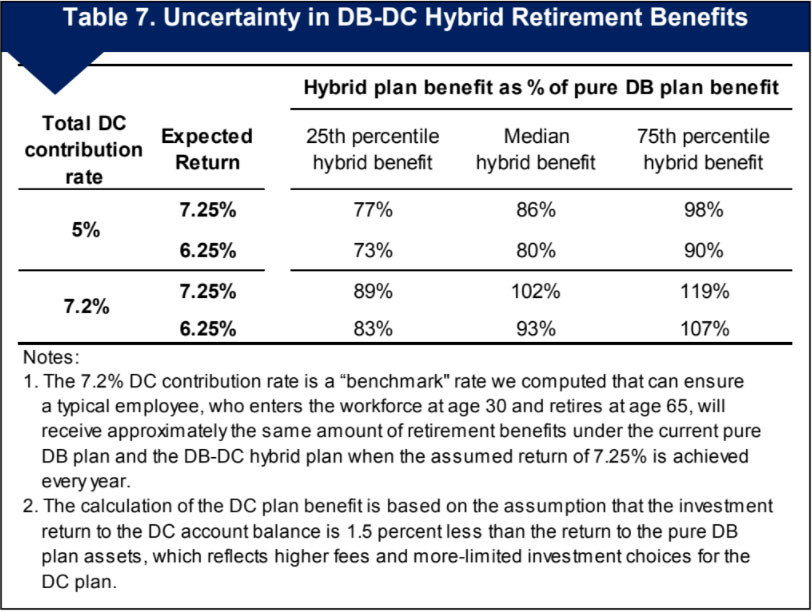

We first compare retirement benefits received by a typical plan member, who entered the workforce at age thirty and retires at age sixty-five, under the pure DB plan and the DB-DC hybrid plan. We use stochastic simulations to obtain distributions of retirement benefits for this member under different scenarios. Table 7 presents the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile hybrid plan benefit as a percentage of the pure DB benefit under different expected returns and total DC contribution rates. With the total DC contribution rate of 5 percent, which is the rate adopted in the recent

Pennsylvania pension reform bill, and expected return of 7.25 percent, the median hybrid plan benefit is about 86 percent of the pure DB benefit, 27 and the 25th percentile benefit suggests that there is a one-in-four chance that the hybrid plan benefit would be less than or equal to 77 percent of the pure DB plan benefit. If the expected return is 1 percentage point lower than the assumed return of 7.25 percent, the median and 25th percentile hybrid plan benefits are only 80 percent and 73 percent of the pure DB plan benefit, respectively.

We also calculate hybrid plan benefits with a 7.2 percent total DC contribution rate (row 3 and 4 in Table 7), which is a “benchmark” rate we computed that can ensure a typical employee, who enters the workforce at age thirty and retires at age sixty-five, will receive approximately the same amount of retirement benefits under the current pure DB plan and the DB-DC hybrid plan when the assumed return of 7.25 percent is achieved every year. When the return assumption of 7.25 percent is met, the median hybrid plan benefit is approximately equal to the pure DB benefit, and there is a one-in-four chance that the hybrid benefit would be less than or equal to 89 percent of the pure DB plan benefit. The hybrid plan benefits become lower when the expected return is 6.25 percent.

The results of the stochastic analysis shown in Table 7 suggest that even when the expected return assumption is met, the hybrid plan benefit can be significantly lower than the pure DB benefit, if the realized investment returns are bad.

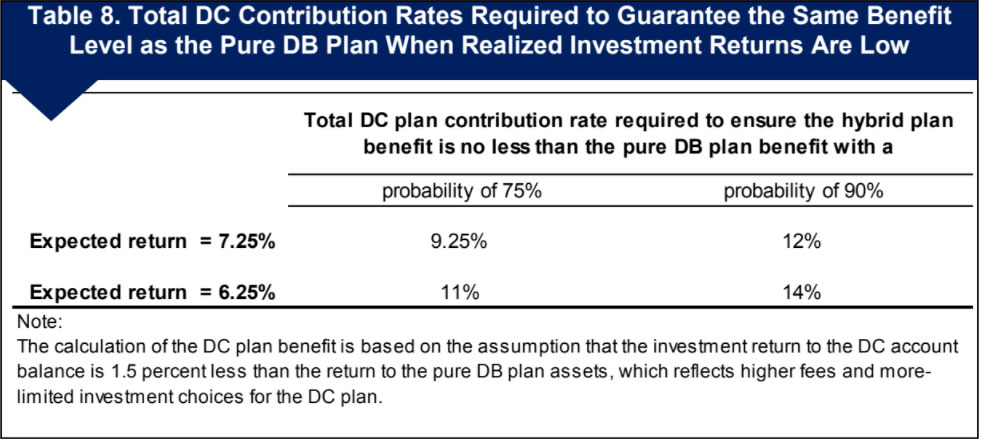

If the hybrid plan were required to guarantee the same benefit level as the pure DB plan even when realized investment returns are low, what DC contribution rate would be needed? We use our stochastic simulation model to determine the minimum DC contribution rates required to ensure the hybrid plan benefits are no less than the DB plan benefit with a 75 percent chance and a 90 percent chance. The required DC contribution rates are shown in Table 8. With the 7.25 percent return assumption met, a 9.25 percent DC contribution rate is needed to secure a hybrid plan benefit that is no less than the pure DB plan benefit with a three-in-four chance, and a 12 percent DC contribution rate is needed to secure this benefit level with a 90 percent chance. If the expected return is lowered to 6.25 percent, the required DC contribution rates would have to rise by another 2 percentage points (11 percent DC contribution rate for a 75 percent chance and 14 percent DC contribution rate for a 90 percent chance). The results show that the DC contribution rate of 5 percent in the recent pension reform bill needs to be at least doubled to guarantee the same benefit level of the pure DB plan under scenarios with relatively bad investment returns.

The results of both deterministic and stochastic simulations show that the hybrid plan reform would have a significant risk-transfer effect on future members who are affected. However, the risk transfer will be small relative to the total pension costs in the next thirty years, because it takes a long time for the hybrid plan to expand and the liability of the hybrid plan will only account for a relatively small share of the total liability of PSERS in the next thirty years. The size of the risk transfer is proportional to the benefit reduction in the DB component of the hybrid plan compared to the pure DB plan, a conclusion that would hold for other states and plans.

The reduced risk in employer pension costs is transferred to employees in the form of uncertainty in retirement benefits. Even when the expected return assumption is met, the hybrid plan benefit can be significantly lower than the pure DB benefit if the realized investment returns are bad. If hybrid plan pension reform aims to guarantee the same benefit level of the pure DB plan under scenarios with relatively bad investment returns, the DC contribution rate of 5 percent in the recent pension reform bill would need to be increased significantly.

We draw several conclusions from our analysis:

- There is a 26 percent chance that the funded ratio of PSERS will fall below 40 percent — what we consider to be crisis territory — sometime between now and year thirty.

- There is a 6.4 percent probability that employer contributions will increase by more than 10 percent of payroll within a consecutive five-year period sometime in the next thirty years. The low risk of sharp increases in employe contribution is partly attributable to the relatively long (ten years) asset- smoothing period.

- The relatively conservative amortization method used by PSERS — twenty-four-year level-percent closed amortization — coupled with full payment of the actuarially determined contribution is key to ensuring the funding security of PSERS.