August 8, 2011

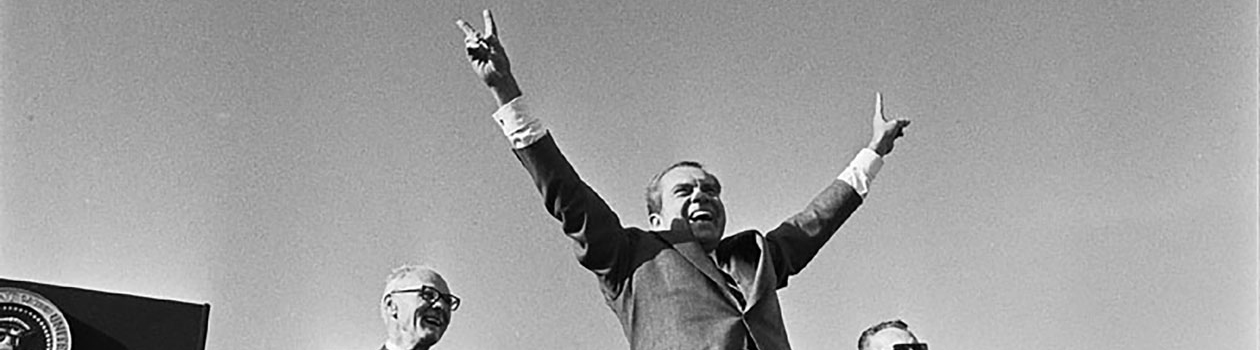

Forty-plus years ago on this date, Richard M. Nixon, then six months into his presidency, addressed the country on national television in prime time to present his domestic program, which he called “the New Federalism.” It is an honor to be here today to recall that occasion and to reflect on how it looks today. It looks good to me.

At the time, I was one of many aides who worked on Nixon’s speech, serving as assistant director for human resources of the Budget Bureau. I was appointed at the beginning of Nixon’s term and served in that role for three years, first under director Robert Mayo and later under George Shultz. It was an exciting time.

I came to my position by a curious route. In the 1968 Republican presidential nominating campaign, I was an aide to Nelson A. Rockefeller responsible for research on domestic issues.1 In the fall of 1968 after Nixon was nominated, Governor Rockefeller met with him to offer assistance, and

in the course of the meeting offered to have some of his staff serve in the presidential campaign. I

was one of the people offered. However, there was a catch. I had left Rockefeller’s employ and by then had returned to the Brookings Institution as a staff member. When George Hinman, New York’s Republican Committeeman, called to tell me I had been “assigned” to the Nixon campaign, I told him that I no longer was a Rockefeller employee, so this was a bit awkward. Hinman’s response was, “Okay, Dick, You work it out,” or something to that effect.

I called the Nixon campaign office, explained the situation, and said that while I did not want to work full-time in the campaign, I would be pleased to serve as a volunteer in transition planning processes, which were then gearing up.

I was asked to organize and head a transition task force on intergovernmental relations, which it was understood would consider proposals for domestic policy initiatives like revenue sharing and block grants (more about them later). I proceeded to do this under the direction of Paul McCracken, who later served as chair of the Council of Economic Advisors under President Nixon. The transition task force planning reports were supposed to be nonpublic input to the new administration.

Before election day, the report of the intergovernmental/revenue sharing task force was sub- mitted. What happened next is interesting. At the time, assuming a Republican victory, I hoped to serve in an appointed position in the new administration and had talked to people about what might be good positions to pursue and how to go about doing so. One person I consulted was John Gardner, nominally a Republican, although he had served earlier as secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) in the Johnson Administration.

As it happened, John Mitchell, who was Nixon’s attorney general designate, looked at the list of transition task forces and noticed that no task force was assigned to “poverty.” He urged that there be one and called John Gardner for suggestions about who should head it.

Gardner, knowing I wanted to go into the new government, said they should ask me to do this for two reasons. One reason was that I am a quick worker (witness the intergovernmental report that was already completed and that he knew about). His second reason for saying I should head the poverty task force was because I didn’t know anything about welfare. He said, “Everyone who works on welfare policy is so doctrinaire that you wouldn’t get an even-handed view from them.”

So I chaired a second task force that recommended a modest program of welfare changes. The main proposal addressed differences among the states in payment levels to poor families. The report recommended a national minimum payment level and a revised grant-in-aid formula for sharing costs between the federal government and the states. The recommendations benefitted both families and state treasuries. We described this as an incremental, not a radical, overhaul. As matters played out once the new administration was in office, the decision was made to endorse a big- ger and bolder welfare reform plan.

By inauguration day I had been designated to become assistant director of the Bureau of the Budget responsible for human resources, a position I was excited about. About that time, a dinner was held to thank members of Nixon’s transition task forces at the Pierre Hotel in New York City. Then came a surprise.

The next morning, an article appeared on the right-hand column above the fold on the front page of The New York Times leaking the report of the “poverty” task force. I was not happy. I was worried I would be blamed for the releasing the report and as a result would not be able to join the new administration. (I still don’t know who leaked the report; anyways, it did not jeopardize my appointment.)

At the start of Nixon’s presidency, an important signaling event occurred for domestic policy that involved Daniel Patrick Moynihan who had been named by President Nixon to direct a new Urban Affairs Council. Earlier, I had talked with Moynihan during the transition about the task force reports I worked on and looked forward to working with him and other Nixon aides and advisors.

In the first week of the new administration, Moynihan held the opening meeting of the Urban Affairs Council.2 Members of the domestic Cabinet and advisors met with the president. As it turned out, I was standing next to Moynihan when the Council assembled. The door to the Cabinet Room opened and President Nixon entered. Moynihan, somewhat nervously I think, said to him, “Mr. President, you know Dick Nathan.” The president’s reply was, “Yes, I know him. I liked his reports, but Everett Dirksen didn’t.” (Dirksen, a member of the U.S. Senate from Illinois, was the Minority Leader.) This was a pretty strong clue that our transition task reports were being seriously considered.

This was six months before President Nixon’s August 8th prime-time television address to the nation announcing his “New Federalism” domestic program. The process for preparing this address, as is usual in high politics, involved intense maneuvering and many players. And it was a slow process. By the time the address was delivered, the key White House staff member for domestic policy was John Ehrlichman, director of the Domestic Council in the White House. During the gestation period for the president’s domestic program, he met often with Domestic Council members and staff and played an active, strong role in the policy process.

I did my best to take advantage of the able and experienced staff of examiners at the Budget Bureau in work I did in the planning process. As it unfolded, and as mentioned it was slow going, we were told that the president was getting impatient. In August, he left Washington for an eight-country international trip during which Ehrlichman, who accompanied him, was to consult with him on the content of the domestic policy address Nixon would deliver on his return. To make sure the job got done (i.e., that the domestic program got worked out), Press Secretary Ronald Ziegler announced a specific date on which the President would present his domestic program to the nation.

The president began his August 8, 1969, address saying he had just returned from an international trip but that tonight his subject was domestic policy. He said, “After a third of a century of power flowing from the people and the States to Washington it is time for a New Federalism in which power, funds and responsibility will flow from Washington to the States and to the people.”

The president described his program in four parts — three of which, he said, would be the subject of special messages to the Congress. Overall, the president said his program sought “a major re- versal of the trend toward ever more centralization of government in Washington.”

Taken together, the New Federalism program was viewed as progressive by most observers. This was still the 1960s. The country had not yet taken the turn to the right that has so characterized our politics since the mid-1970s.

The four parts of the speech were welfare reform, revenue sharing, a new job training and placement program, and what he referred to as a “revamping” of President Johnson’s Office of Economic Development (OEO) that oversaw antipoverty programs.3

In the media and in national politics, the biggest item on this list was welfare reform. Revenue sharing was second. The other two items pretty much faded from view.

The reaction to the president’s address was positive — indeed, effusive.

To editors of The Economist: “It is no exaggeration to say that President Nixon’s television message on welfare reform and revenue sharing may rank in importance with President Roosevelt’s first proposal for a social security system in the mid-1930s.”

The San Francisco Chronicle said of the president’s welfare proposal, “the Nixon measure has the great advantage of being not only ‘noble in purpose but also suited to the needs of the day and the will of the people.”

On revenue sharing, the editors of the New York Daily Newssaid: “Revenue sharing would be a giant step in the direction of dismantling the cumbersome apparatus that has grown up in Washington. It can’t happen too soon to suit us.”

The Christian Science Monitor called the president’s program “a major watershed — socially, economically and politically.”

Later, looking back on Nixon’s domestic presidency, Tom Wicker, in his book on the Nixon presidency, One of Us: Richard Nixon and the American Dream, praised his domestic program. In a similar vein and including President Nixon’s health reform plan announced in 1971, Joan Hoff in her book, Nixon Reconsidered, said that taken together his proposals on welfare and health reform “were so far in advance of his time that congressional liberals preferred to oppose them rather than allow Nixon credit for upstaging them.”

Although in the 1968 campaign Nixon’s speeches and statements on domestic affairs were general as is customary on the stump, his main points were hard hitting. He repeatedly criticized the role and record of the federal government in domestic affairs under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson and called for changing the relationship between the national government and the states. The president said, “For years now, the trend has been to sweep more and more authority towards Washington. Too many decisions that would better have been made in Seattle or St. Louis have wound up on the President’s desk.” (September 1968 radio address).

In effect, Nixon’s philosophy was: Yes, we should solve problems — but in a better way, a middle way. As the president’s ideas were spelled out, what I found convincing was that his ideas about the “New Federalism” weren’t contained just in printed remarks and formal statements. When the president talked extemporaneously, he was, if anything, stronger and more articulate in describing the New Federalism.

The basic idea of American federalism, which James Madison called the “Compound Republic,” is the division of power between the national government and the states in a new way. This was fundamental to the Founders, namely the existence of two levels of government, each responsible to its electorate. Every citizen is a citizen of the two governments, national and state. This concept has the following virtues:

A central purpose of Nixon’s “New Federalism” was to sort out governmental functions, some appropriately and best centralized, and others best left to state and local governments. Picking up on the point earlier about how the President often expressed these ideas strongly in his own words, here is a statement he made at a press conference about an area in which the Nixon Administration exercised strong national leadership — the environment:

When we look at the problem of the environment and where we go, there are these thoughts I would like to leave with you: first that the necessity of the approach is national. I believe in States responsibilities. This is why revenue sharing to me is a concept that should be adopted. On the other hand, when we consider the problem of the environment it is very clear that clean aid and water doesn’t stop at a State line.

And continuing, Nixon said,

And it is also very clear that if one State adopts very stringent regulations, it has the effect of penalizing itself as against another State which has regulations which are not as stringent in- sofar as attracting the private enterprise that might operate in one state or another or that might make that choice. That is why we have suggested national standards.

Nixon’s “New Federalism” selected some functions, like the environment, involving what economists call “spillovers” as areas where national action is appropriate. In other areas involving service-type activities (for example, job training and community development), states and local communities were regarded as being better able to diagnose their own needs and set their own priorities.

Welfare, the subject treated next, illustrates this point about sorting out functions.

Welfare reform got top billing in President Nixon’s August 8 television address. Speaking about the failures of domestic policies of the past, the president said, “Nowhere has the failure of government been more tragically apparent than in its efforts to help the poor, especially in its system of public welfare.” The president’s “family assistance system” would, he said, “make it possible for people — wherever in America they live — to receive their fair share of opportunity.”

Indeed, this objective (leveling the playing field among the states) reflects the economic concept of “spillovers” mentioned earlier. The idea is that because people move from place to place and there are often substantial differences in the fiscal capacity of states and communities to aid the poor, there should be a reasonable level of evenness in terms of the dollar amounts of assistance poor families receive. This can be seen as fitting the decentralization purpose of the New Federalism by decentralizing welfare directly to families and individuals.

Later, in a speech that President Nixon gave on the basis of notes at the November 2, 1969, White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health, Nixon elaborated on this point. Addressing Pat Moynihan (who was in attendance), Nixon said “The task of Government is not to make decisions for you. The task of Government is to enable you to make decisions for yourself. Not to see the truth of that statement is fundamentally to mistake the genius of democracy.”

The subject matter of welfare reform is not easily summarized.5 Recipients were required to work. No mistake about it. At the same time, the aim was that there should be incentives so that when they earned more money, they wouldn’t just lose all their welfare assistance. This is the essential idea of a negative income tax. And as it turned out, it was the Achilles heel of welfare reform. In hot and heavy Congressional and public debates about the Family Assistance Plan (FAP), issues emerged that kept requiring (or at least appeared to require) upward cost adjustments that ultimately brought FAP down.

All of this was the subject of intense debate. Moynihan and Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Robert Finch pressed the negative income tax idea. On the other side, Presidential Counselor Arthur Burns and others (notably Martin Anderson, who worked for Burns) argued that the economics of this approach would not work. As it turned out, they didn’t.

Many people inside the administration played a role in welfare reform planning. This included, among others, Secretary Finch and HEW Under Secretary John Veneman; John Ehrlichman, Pat Moynihan, Arthur Burns, Secretary of Labor George Shultz,6 Edward Morgan, Ed Harper, Henry Cashen, and Ken Cole on the Domestic Council staff; Martin Anderson assisting Burns; Paul O’Neill and others at the Bureau of the Budget office; John Price working with Moynihan; Bob Patricelli at the Department of HEW; and Herbert Stein, a member of the Council of Economic Advisors.

Ultimately, the debate in Congress about the Family Assistance Plan derailed FAP because of the work-incentive feature. The plan passed the House twice, but failed in the Senate. Nixon, however, was able to achieve important, though less prominent, parts of his welfare reform program involving aid for the aged and disabled.

In his August 8 “New Federalism” address, the President described his revenue sharing proposal as a way to reverse the tide of centralization “to turn back to the states a greater measure of

responsibility — not as a way of avoiding problems, but as a better way of solving problems” (emphasis added).8 This would be a new middle way. Revenue sharing was a key component. Nixon said revenue sharing would begin in the final six months of fiscal year 1971 at a half-year rate of a one-half billion dollars. (By contrast, the first-year cost estimate in the address for the FAP welfare reform was $4 billion.)

As matters turned out, the nation’s governors, who were to receive one-third of the revenue sharing funds, and the heads of local governments, who would receive two-thirds, did not march in lock step to fight for revenue sharing. The reason was the money. The proposal initially presented wasn’t big enough for them. Try as they could, White House officials responsible for Congressional liaison couldn’t get the measure moving in Congress.

What to do? Answer — The Administration upped the ante. In the budget for the 1972 fiscal year presented in January 1971, the president proposed a $16 billion per year “investment in renewing State and local government” — $5 billion per year for revenue sharing (a five-fold increase) and $11 billion for “block grants” described in the section that follows.

This did the job. In 1972, on the eve of the presidential election, checks were mailed to the 50 governors and the heads of over 37,000 local governments as the first installment of shared revenue. The law stayed in effect for over a decade; total payments were $51 billion. The eventual demise of revenue sharing reflected budget woes and a lack of enthusiasm on the part of Nixon’s presidential successors, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

The formula for allocating revenue sharing funds involved detailed and intricate decision making in which many people took part, with leadership at the time from the Treasury Department under Assistant Secretary Murray Weidenbaum.

Block grants originated in modest form under President Johnson. Their purpose is to consolidate existing so-called “categorical grants” into broader and more flexible grants to state and localities in order to get rid of the particularistic rules and red tape of the narrower component grants.

The $11 billion that the president said was for block grants was for combining existing grants into six new block grants consisted of new funds and currently existing funding in the following functional areas: urban development, rural development, education, job training, and law enforcement.

The president emphasized that his plan would provide “more money and less interference.” Depending on how you keep score, three of these blocks were adopted, those for urban and rural community development and job training.

Fiscally, the most important point to make about Nixon’s block grants is that they added money in the form of what were labeled as “sweeteners.” The interesting comparison is with President Reagan’s approach. A decade later when he proposed grant blocking, the rationale was to save money. There were no sweeteners.

Decision-making processes for grant blocking were interesting. They were led by the White House Domestic Council. In particular, I recall a 7:30 A.M. planning meeting of Domestic Council and budget staff members and others when John Ehrlichman said the president would meet later that morning with domestic Cabinet secretaries on block grants. After the planning meeting, I asked Ehrlichman if I could attend. He said that would be fine.

At the meeting, when the Cabinet group was assembled, Ehrlichman began the discussion, turning to me and said, “Dick Nathan will explain how block grants work” or something to that ef- fect. I was taken back, but proceeded to outline the ideas and aims of block grants. Attorney General Mitchell (his agency was responsible for a law enforcement block grant) spoke first. He said all this is good, and beyond that I don’t recall that there was much discussion. That was it.

Later, as legislation for block grants was readied for submission to the Congress, Ehrlichman individually briefed the affected Cabinet members about decisions that had been made. I attended these meetings. Most of them went smoothly, but George Romney, secretary of Housing and Urban

Development, was indignant. He complained this was the first he had heard about how the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) would work and that he and his agency should have been consulted. It took awhile to calm things down, although as it turned and most experts probably would agree CDBG was the most successful of the Nixon block grants. The CDBG block grant is still in effect today essentially in the form it was first proposed.

In his 1971 State of the Union Message, in which President Nixon elaborated on his domestic program, he also announced “a far-reaching set of proposals for improving America’s health care and making it more available to more people.” As later spelled out, this plan was similar in a number of ways to what was enacted in 2010. Nixon’s plan was named the “Family Health Insurance Plan” or FHIP, which of course led to commentary and news stories about “FHIP and FAP” The president sent a special message to Congress on February 18, 1971, laying out his health insurance reform plan, which included a mandate on employers to provide coverage for their workers. The Wall Street Journal called it a good strategy; better, the editors said, than Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s plan, which had been introduced just before Nixon’s.

Writing at the time in reaction to Nixon’s health reform plan, James Reston said, “For more than a year now he [Nixon] has sent to Capitol Hill one innovative policy after another: welfare reform, revenue-sharing program, government reform, postal reform, manpower reform, Social Security Reform, reform of the grant-in-aid and others…. It is not necessary to agree with his proposals in order to concede that, taken together, they add up to a serious and impressive effort to transform the domestic laws of the nation.”

Eight presidencies later, it is worth asking if President Nixon’s successors had “new federalisms” similar to his. Two examples stand out, President Reagan’s program and what can be labeled the “New(t) Federalism” of the Republican majority in the 104th Congress elected in 1994.

President Ford signed the most important block grant advanced by Nixon, the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG). It is notable that the Ford Administration managed this program in the “hands off” spirit that was intended (that is, let local officials decide). The Carter Administration’s federalism policies were different, both for regulations attached to CDBG funding and, as mentioned earlier, and for revenue sharing.

The most notable champion of federalism aims and ideas among later presidents was Ronald Reagan’s, but with a different spin. Despite the fact that President Reagan didn’t use the phrase “new federalism,” the press often did in describing his program. Reagan’s federalism policies for the country started out with a bang. He proposed what was called the “swap and turn back” plan, whereby Medicaid would become fully a federal program and the states in exchange would take over welfare.

Reagan’s plan didn’t get far. In retrospect, leaders of the National Governors Association and other groups of state officials still today regret that they didn’t put shoulder to the wheel to get Reagan’s swap-and-turn-back plan adopted. (The reason of course is that Medicaid, which has been the “800-pound gorilla” of state finances ever since, would have become a federal government fiscal responsibility.)

Federalism politics heated up next in the 1990s. When Clinton’s national health reform was dramatically rejected, the mood of the nation on domestic policy shifted. Republicans came into power in the 104th Congress elected in 1994, and among other things sought to turn the federalism tide. They did this through a strategy of “big-time grant blocking” in the appropriations process.

The difference between the Nixon and Reagan Administration’s grant-in-aid policies and the “New(t) Federalism” was that the latter focused on blocking open-ended entitlement grant programs, really big targets. Both for Medicaid and welfare, the 104th Congress tried to cap the money for these programs by converting them from being open-ended appropriations to being closedended block grants to the states.

Despite the fact that President Clinton vetoed most of their efforts to do this, there was one big exception — for welfare.

Initially, the 104th Congress sent omnibus budget bills to the president bundling several entitlement and other domestic programs into one big legislative package. Clinton, in his veto messages on these measures, picked out one or two issues as his basis for rejecting the whole plate full. In particular, he opposed converting Medicaid into a block grant.

So, Republicans hit on a new strategy. They would just send President Clinton a welfare block grant. They would put President Clinton on the spot. Recall that throughout Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, he trumpeted welfare reform. He kept using a slogan that always got strong applause: “We will end welfare as we know it,” adding that under his program it would be “two years and out.”

The year 1996 was a presidential election year. Taking advantage of the opportunity, Republicans in the Congress sent President Clinton a free-standing welfare block grant. Just for welfare. It was projected that this block grant would reduce the growth of spending for welfare. Another important feature was time limits on welfare payments. The 104th Congress challenged the president.

Just veto this one.

The result was something of a political surprise. After some back-and-forth negotiations,

Clinton signed legislation to establish a welfare block grant with time limits. But more than that, he championed it! The new program was called “Temporary Assistance to Needy Families,” and it still exists. It replaced Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC).

I want to go back now to the Nixon years. The changed political mood of the 1980s was part and parcel of a turn to the right in the country on social and domestic issues. Actually, the turn-around began in the 1970s, and was already bubbling up in the late 1960s as reflected in a changed tone on domestic affairs at the end of Nixon’s first term. A notable expression of President Nixon’s change was contained in a newspaper interview he gave towards the end of the 1972 election campaign. The reporter for this story was Garrett D. Horner of the Washington Star-News. Horner met with the president at his new home in San Clemente, California for an interview conducted in what Horner said was “a relaxed manner.” He said the president “repeatedly indicated … a conservative course.”

The president said he would “shuck off” and “trim down” social programs “set up in the 1960s that he considers massive failures largely because they ‘just threw money at problems.’” In particular, the president said he would cut staff and programs in HUD, HEW, and Transportation that “are all too fat, too bloated.” He added that these measures would accomplish “more significant reform than any such program since Franklin D. Roosevelt — but “in a different direction.” Criticizing “what he called ‘the limousine liberal set’” of the northeast and the “liberal establishment,” the president said he wanted to end “the whole era of permissiveness.” Summing up, there would be “few social goodies” in his second administration.

Times had changed. It was now the seventies. Still, the newspaper in this case was conservative and no doubt regarded as a good vehicle for signaling to Republican members of Congress and conservative constituencies. In a related initiative at the time, the president advanced a broad reorganization of federal government domestic agencies. This was to be accomplished under four “super-secretaries” as part of a management overhaul spearheaded by John Ehrlichman. The goal was a forceful one, to change the behavior of domestic bureaucracies.

The Horner interview and the reorganization plan, however, were not the end of the story. The administration’s policy and management approaches changed again. The program and budget proposals for FY 1975 were more conciliatory. Many proposed budget changes and cuts from the previous year were not reintroduced.

Looking at all of this, a reader of a draft of this paper asked, “What about now? Did the “New Federalism” ideas have a sustained effect? Where does all of this stand today?” In my mind, the answer is: Yes. Decentralization is having a comeback. Leaders in the Congress and indeed other governments too — Great Britain is a case in point — are taking up the cudgels, seeking ways to decentralize and strengthen state and local governments.

For me, personally, the take away from this experience is pride — pride to have been a part of serous efforts by talented and accomplished colleagues who worked tirelessly (as you have to inside the political cauldron) and blended policy and politics in the public service. In particular, working under George Shultz, director of the OMB, was a treat and special opportunity for me. I thank my many colleagues.