Harm reduction is an evidence-based public health approach intended to reduce the harmful impacts of behaviors associated with substance-use disorder (SUD) and alcohol-use disorder (AUD). Along with prevention, treatment, and recovery it is one of the four key elements of federal and New York State overdose prevention strategy. SUD treatment and recovery services focus on the full cessation of drug use, generally through therapeutic and/or medication-assisted treatments (MAT), and are credited with reducing morbidity and mortality associated with increasing overdose rates.

Harm reduction’s primary goal is not necessarily to stop all drug use but to reduce the harms such as infectious disease spread and HIV transmission through the sharing of needles and the probability of death from overdose. Harm reduction focuses on reducing the risky behaviors and death associated with drug use, not complete abstinence. The philosophy underpinning harm reduction is that illegal drugs are the problem, not the people with use disorders (PWUD).

Harm reduction can be targeted at either the individual or community level. The range of approaches under the harm reduction umbrella is broad including relatively uncontroversial programs such as expanding access to the emergency overdose response drug naloxone (Narcan) which has been in effect in New York since 2006. Harm reduction also includes safe or supervised consumption sites (SCS) where users can use pre-obtained drugs under the supervision of trained personnel. While in use internationally for decades, STSs are politically unpopular in the US and the first in the nation opened in New York City in November 2021.

Harm reduction services in New York represent a “fully integrated client-oriented approach” to health and well-being, including but not limited to prevention and response for SUD, HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C viruses, and other illnesses that put substance users at risk. Currently, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) runs most harm reduction programs. Collaboration between the NYSDOH and the NYS Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS) has allowed for the swift development of SUD prevention programs and support systems over the last few decades.

Harm reduction focuses on reducing the risky behaviors and death associated with drug use, not complete abstinence.

This piece presents three harm reduction strategies: syringe exchange programs (SEPs), fentanyl-detecting test strips (FTS), and naloxone administration. It also discusses the regulations and policies enacted to support these strategies in New York State. Each of these strategies targets a different type of harm associated with drug use and SUD. Syringe exchange programs prevent the transmission of blood-borne pathogens among drug users who share needles; Fentanyl-detecting test strips identify whether drugs contain potentially fatal levels of the strong synthetic opioid fentanyl; and naloxone administration can reverse an in-progress opioid overdose. Used in conjunction with treatment, these strategies can save lives.

Harm Reduction Programs

- Syringe Exchange Programs

In the early 1980s, needle exchange programs were first founded in Europe in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the growing problem of injection drug use/users (IDUs) in European prisons. In 1992, Switzerland began utilizing syringe exchange programs in prisons, which ultimately decreased the prevalence of infectious diseases related to IDU. The increase in using and sharing of contaminated injection drug equipment and needles, combined with unsanitary conditions, contributed to the spread of HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C viruses amongst incarcerated people, eventually impacting the surrounding communities. These viruses spread only through sexual contact or direct contact with contaminated blood. Limiting blood-to-blood contact through needle sharing can have a profound impact on disease transmission.

The first legal US needle exchange program was founded by Jon Parker in New Haven, CT, in 1986 to distribute sterile needles to drug users to prevent HIV/AIDS transmission. Following the height of the AIDS epidemic, which was particularly devastating in New York City in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a shift from the more punitive approach to drug use to a harm reduction and treatment approach for SUD, which included implementing SEPs.

The first SEPs were authorized in New York in 1992 under four pilot programs run by a community group that already had experience working with people who use drugs (PWUD). The sites were located in the Bronx, East Harlem, Harlem, and the Lower East Side, and funded by the American Foundation for AIDS Research and NYSDOH. The pilots successfully decreased shared equipment amongst PWUD, foreshadowing the success of today’s NYS SEPs, which serve as extensive harm reduction programs that mobilize and train community members to recognize and respond to overdoses and their related risks. Today, SEPs function as community-based harm reduction services that provide free sterile syringes and collect and properly dispose of used needles from PWUD to reduce disease transmission.

Beyond the syringe exchange itself, SEPs generally provide services which aid in reducing harm associated with drug use. While their primary purpose is to provide clean and unused hypodermic needles at little or no cost, NYS SEPs offer a variety of wrap-around services, including individual and peer harm and risk-reduction counseling, HIV, STI, and Hepatitis counseling, screening, and testing, behavioral interventions, mental health counseling, opioid overdose prevention training, safety planning, aftercare for overdose, and care management. Programs can also include holistic healthcare such as ear-point acupuncture and cultural competency training for other providers to serve PWUD better.

The NYSDOH helps provide needles and harm reduction supplies as needed since these programs receive limited federal government funding. NYS policies and procedures for SEPs allow for the regulation and security of all syringes and supplies, for example, to ensure the safety of staff, volunteers, and program participants. As of 2021, there are 24 approved and functioning SEPs in NYS, with 14 programs across 54 sites in NYC and 10 programs spanning 26 locations across the remainder of the state.

- Fentanyl-detecting Test Strips

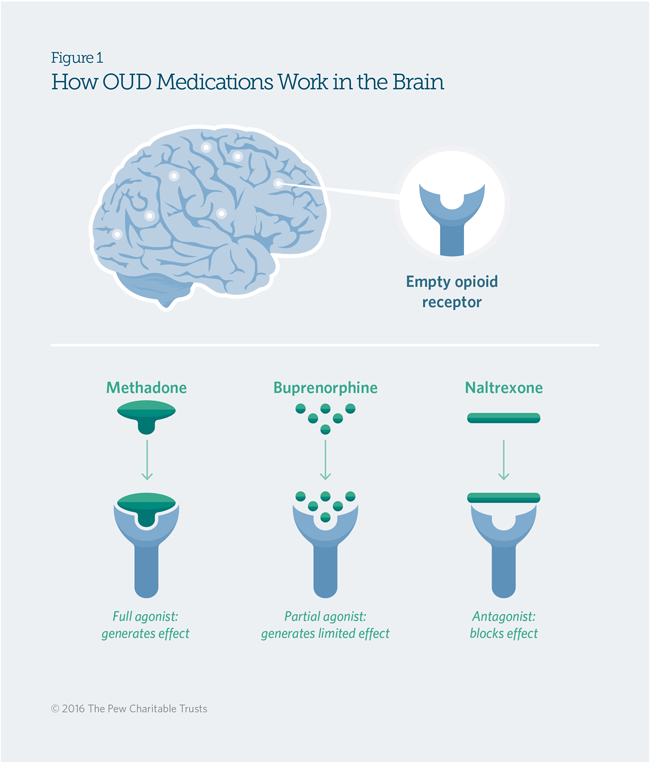

The dramatic 2020 surge in overdose deaths can be attributed almost entirely to fentanyl and related synthetic opioids. Synthetic, fentanyl-containing opioids are 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, meaning they can produce more harm than a standard opioid. As soon as an individual injects a fentanyl-containing opioid, it works by binding itself to opioid receptors in the brain that control levels of pain and emotions. Synthetic opioids have a similar effect on the brain to other opioid analgesics, including morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, methadone, and heroin. Effects include extreme happiness, drowsiness, nausea, confusion, constipation, sedation, tolerance, respiratory depression and arrest, unconsciousness, coma, and death.

The dramatic 2020 surge in overdose deaths can be attributed almost entirely to fentanyl and related synthetic opioids.

While fentanyl was initially approved by the FDA (as Actiq) to treat cancer patients with moderate to severe breakthrough cancer pain in 1998, it soon made its way into the illicit drug supplies. Synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, are the leading cause of overdose deaths, with 72.9 percent of all opioid-induced overdose deaths nationally associated wholly or in part to synthetic opioids. The other 27 percent includes heroin, tramadol, codeine, methadone, and prescription opioids, such as morphine. Fentanyl is particularly dangerous because it can be lethal in extremely small and hard to detect quantities.

Individuals are not always ingesting fentanyl intentionally. Over the last decade, a growing number of opioid overdose deaths have been traced to the adulteration of other drugs, including heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamines, with fentanyl and its analogs. Fentanyl is most dangerous when it is illicitly manufactured and sold through illegal markets.

In response to the surge in fentanyl overdoses in the past few years, the State, especially in NYC, has expanded the use of fentanyl-detecting test strips as a harm reduction strategy to identify fentanyl and other synthetic opioids in opioids and other drugs. FTS can be particularly valuable to people who use cocaine and methamphetamine because users of these stimulant drugs may be untrained in harm-reduction and overdose-prevention strategies specific to opioid drugs. Simulant and opioid overdoses have different physical symptoms. In addition, fentanyl has been found in counterfeit prescription opioid pills, which contain a much larger opioid dose than the legitimate pill, and can harm users who ingest a different dose of opioids than intended.

According to the CDC, as of April 2021, federal funding can be used to purchase rapid FTS for distribution to the public. NYC-based studies that distributed FTS to PWUD found that individuals who received a positive FTS result changed their behavior by slowing down usage, using a smaller dose, or disposing of the fentanyl-containing drug. While FTS are still an emerging harm reduction tool, NYS may be able to use them to supplement existing harm reduction programs and distribute them through established channels.

- Naloxone Administration

The development of naloxone was arguably the first harm-reduction strategy that targeted opioid overdose. Naloxone was synthesized in the 1960s and was first approved by the FDA for opioid reversal in 1971 but was generally only used in hospitals, emergency rooms, and by anesthesiologists to prevent overdose due to medical errors. Harm reduction communities began to advocate for access to naloxone in the 1990s, with the first public non-medical uses in 1996. The NYS Public Health law (Article 33, Title 1 §3309) legalized naloxone administration programs on April 1st, 2006. Naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan®, is an FDA-approved prescription and emergency medication administered to a person experiencing opioid overdose as a nasal spray or injection to reverse the overdose quickly. Naloxone alone does not serve as a long-term treatment for SUD and can only be used to reverse an overdose. Nasal spray formulations of naloxone are now available to the general public without a prescription.

Programs that train people to administer naloxone are crucial harm reduction measures. Such programs along with policies that make naloxone use, distribution, and authorization legal can reverse more overdoses and save more lives. NYS programs train professionals and community members to administer FDA-approved naloxone and assist in the emergency response to opioid-related overdoses. Once naloxone is administered to an individual experiencing signs and symptoms of an overdose, such as shallow breathing or blue/purple lips, it immediately blocks the opioid receptors in the brain, reversing the opioid overdose in the brain and body, which can quickly save their life. Thus, the training, distribution, and administration of naloxone is critical for reducing the harms associated with opioid overdose and lowering the risk of overdose death. Naloxone administration does not harm a person who is not experiencing an overdose. OASAS currently offers a free naloxone training certificate program to students, via the University at Albany Collegiate Recovery program, and the general public. First responder training is also available statewide. All participants receive free Narcan rescue kits after completing a training session.

SOURCE: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

In addition to training programs, NYS most recently employed the Naloxone Co-payment Assistance Program (N-CAP) in 2017 as a pharmacy benefit for New Yorkers who hold prescription coverage via their insurance plan. Under N-CAP, patients will receive prescription naloxone with minimal out-of-pocket expenses when picked up at one of the 2,000 participating pharmacies across NYS. There is no individual enrollment necessary to participate in the program; however, the monthly amount of naloxone covered may be limited depending on the primary healthcare insurer. While the state continues to expand naloxone administration programs, training first responders and community members to administer this life-saving medication is critical.

The Next Steps in Harm Reduction

Harm reduction programs have been invaluable in New York’s effort to combat the ongoing overdose epidemic. Syringe exchange programs, fentanyl-detecting test strips, and naloxone administration programs have collectively succeeded in saving lives by preventing disease transmission and overdose death, as well as connecting people who use drugs with both treatment and support programs and other wrap-around services.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, treatment, prevention, and harm reduction strategies appeared to be succeeding. The rapid increase in overdose deaths leveled out in 2018 and 2019, only to jump nearly 30 percent in 2020. This resurgent overdose epidemic has resulted in renewed interest in additional types of harm reduction strategies. Some of these strategies include Drug User Health Hubs, first piloted by NYSDOH in 2016, and supervised consumption sites (SCS) in 2021. On November 30th, 2021, NYC became the first US city to open two SCSs in East Harlem and Washington Heights. SCSs represent an expansion of harm reduction programs, as they provide clean needles, administer naloxone, and offer users access to counseling, referrals, and other treatment services. In a future piece we will explore these newer models of harm reduction services.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Abigail Guisbond is a graduate research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government