Photo: The Kingfisher Project’s Sky Lantern Release in Jeffersonville, New York, in November 2017 commemorated those whose lives have been affected by narcotics and opioid addiction.

Today is International Overdose Awareness Day, a global event held each year to raise awareness of drug-related overdose deaths and reduce the stigma surrounding addiction. More than raising awareness, the day also gives us a chance to ask two important questions: Why are so many people dying? And, what should we be doing about it?

Why Are So Many People Dying?

Overdose deaths don’t affect populations equally. In the United States, opioid overdose death rates are highest in rural communities. In a previous blog, we discussed some of the reasons why opioid misuse has become such a problem in rural communities. Contrary to the popular narrative that social and economic deterioration in rural communities account for the current crisis (the so-called “deaths of despair” hypothesis), we suggest, instead, that access to physicians who readily prescribe opioids in rural areas may hold the clue to current disparities between urban and rural drug use.

But how opioid misuse becomes a problem is only one part of the puzzle as to why death rates are so high. The other piece is what prevents local governments from making significant progress to stem the tide.

We went down to rural Sullivan County to learn more from people on the frontlines. Certainly, rural communities — like Sullivan — do not have the resources or support they need to deal with a problem of this magnitude. The county’s hospital does not have a detox unit. There are only a handful of drug rehabilitation facilities. Ironically, as the crisis in Sullivan worsened, more facilities closed. Services that other New York State residents might take for granted — access to specialized medical care, public transportation, available and affordable housing — just aren’t there, creating a real barrier for county leaders trying put an end to the crisis.

While Orange County benefits from greater resources and infrastructure, there is no indication of the epidemic slowing down here either. Despite every effort to the contrary, the overdose death rate in both Sullivan and Orange counties continues to climb.

Do rural communities face greater burdens? And, do they have fewer resources to address them? We decided to find out by looking at neighboring Orange County to see if it were any more successful in the ongoing fight against opioid misuse. We discovered that while Orange County typically has more resources and infrastructure to deal with the problem, it — like many other counties — struggles to get ahold of opioid misuse and overdose deaths as heroin and fentanyl become more readily available.

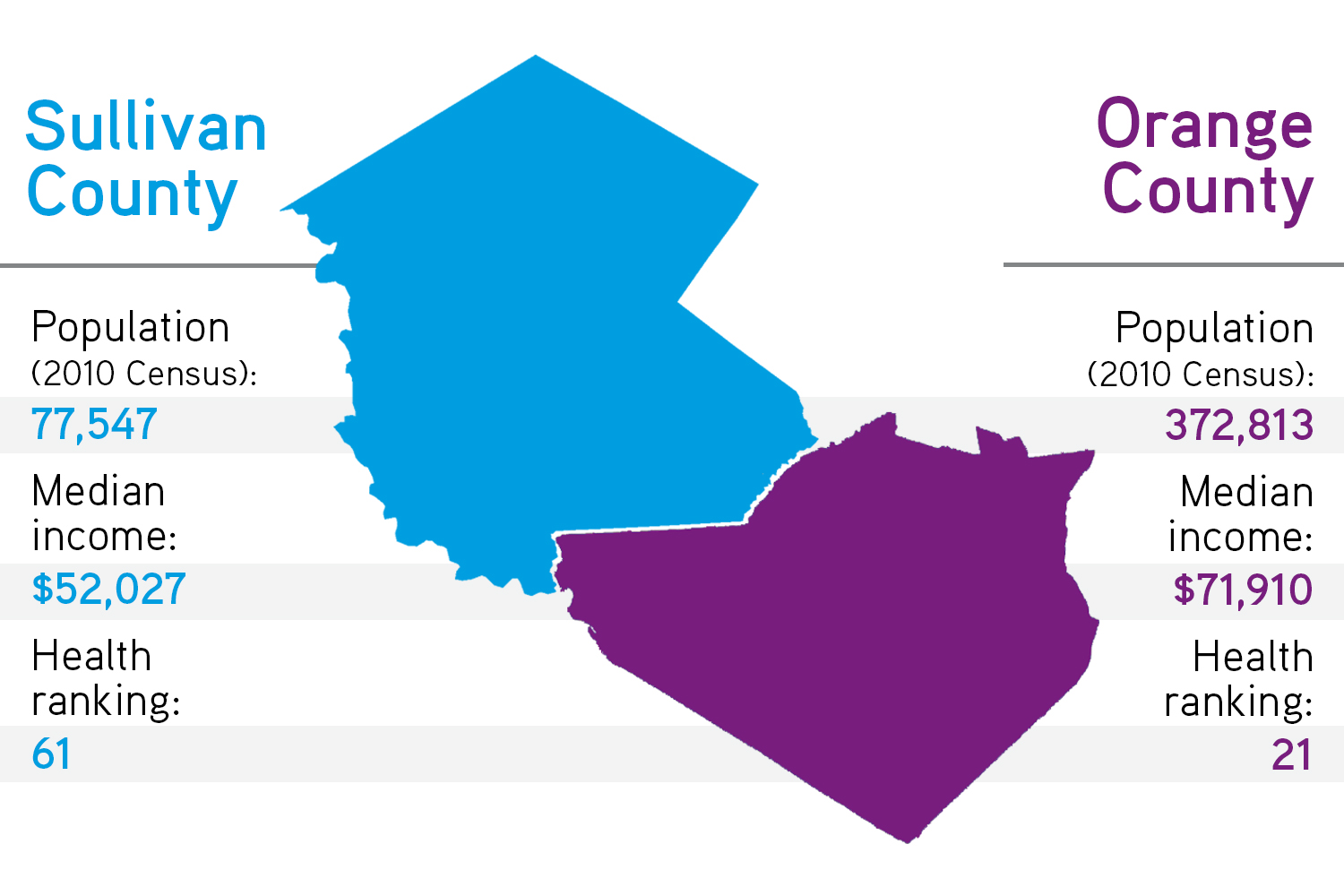

Sitting just a few miles to the southeast, Orange County ranks higher on measures of population, income, and health than Sullivan. Its population is nearly five times larger, and more than three quarters of its population live in urban areas.

Socioeconomic and health indicators suggest that suburban counties like Orange have greater capacity to deal with the opioid problem. Indeed, people in Orange make more money (median income $71,910, compared to $52,027 in Sullivan County) and fewer live in poverty, even though the unemployment rate is comparable across both counties. In the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s annual ranking of county health by state, Orange generally ranks in the top third, much higher than Sullivan.

At the most basic level, the sheer size of government in Orange is bigger. The District Attorney’s Office, for example, employs twelve investigators, nineteen clerical workers, and forty-five assistant district attorneys compared to the eight assistant district attorneys in Sullivan County. Orange also employs an epidemiologist who develops public health assessments and countywide improvement plans.

Orange has a larger revenue stream as well. In 2017, the county collected $279.6 million in sales tax, which helps fund the local government and its forty-two towns, villages, and cities. Sullivan, by comparison, took in just under $40 million.

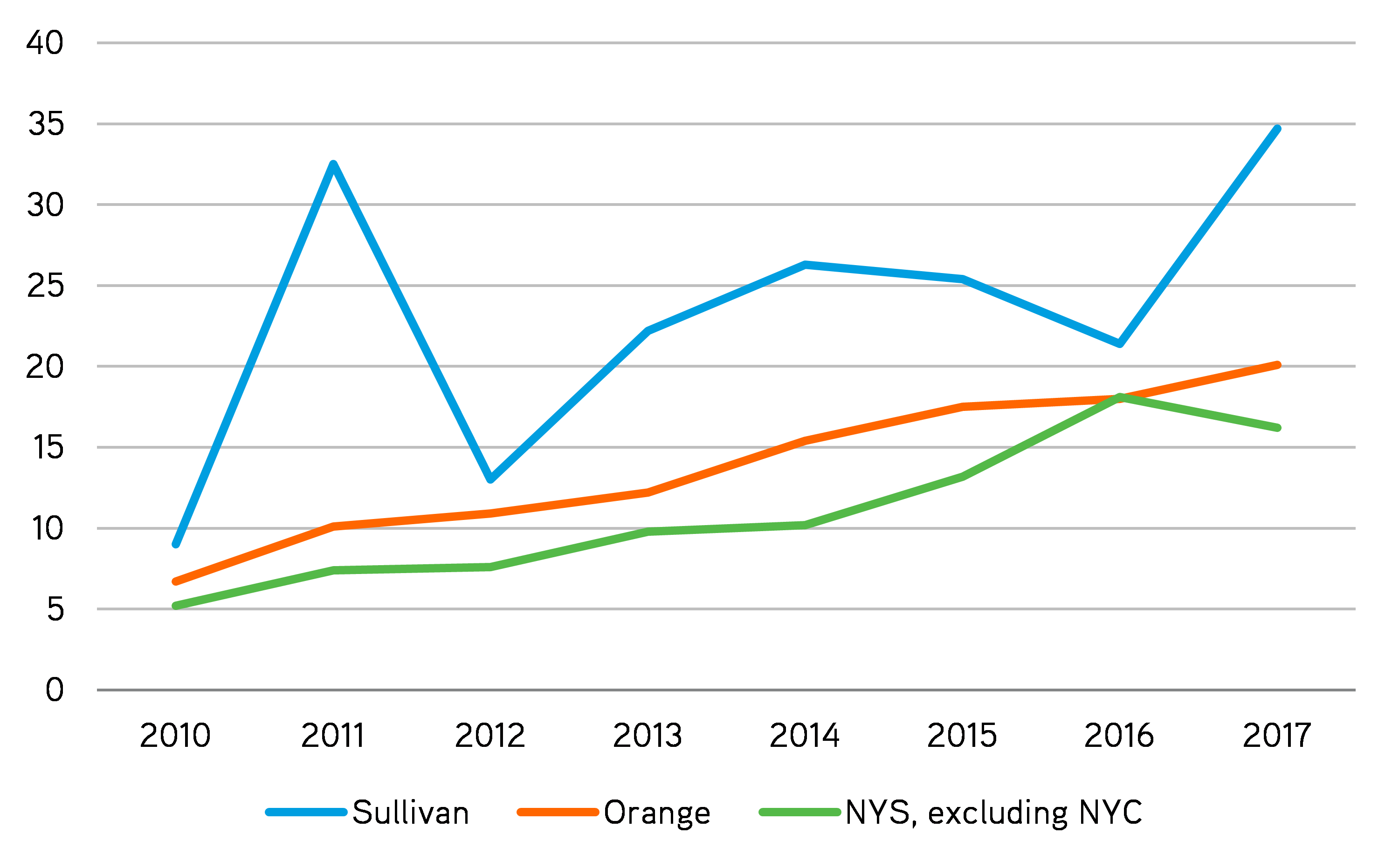

While Orange County benefits from greater resources and infrastructure, there is no indication of the epidemic slowing down here either. Despite every effort to the contrary, the overdose death rate in both Sullivan and Orange counties continues to climb. In Sullivan, the number of opioid-related deaths in 2017 was nearly four times higher than the number of deaths in 2010. For Orange, it was nearly three times higher than in 2010.

Overdose Deaths Involving Any Opioid, per 100,000 People, 2010-17

Source: Authors’ analysis of “Opioid-related Data in New York State.”

Even though Orange and Sullivan are differently resourced communities, their experiences with the opioid epidemic are at times indistinguishable. In both counties, we heard about staffing shortages and the difficulty of hiring well-qualified addiction specialists: “There aren’t enough of them and they are poorly trained,” said one provider in Orange. As in Sullivan, Orange County also experiences difficulty getting people into treatment, connecting families to services, and dealing with state agencies. “We’re desperate,” one public health official told us in Orange County. “We’re desperate, as so many other communities are, to get a handle on this.”

Why isn’t a county with greater resources and infrastructure able to move the needle on overdose death rates? The answer has less to do with local governments than with the nature of the drug itself. As one Orange County official observed: “We really felt like we were getting a pretty good handle on it. We thought we were managing the number of deaths and doing a great deal of work … and then fentanyl hit the streets.”

As in Sullivan, Orange County also experiences difficulty getting people into treatment, connecting families to services, and dealing with state agencies. “We’re desperate,” one public health official told us in Orange County. “We’re desperate, as so many other communities are, to get a handle on this.”

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid fifty times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. A single dose of fentanyl as small as two grains of salt can be fatal, yet drug traffickers are using it at an alarming rate to cut heroin and boost profits — oftentimes without the buyer’s knowledge. Making matters even worse, the likelihood of overdosing on heroin or fentanyl is higher than for other drugs because tolerance for opiates diminishes very quickly. As one addiction specialist explained to us, if people who are incarcerated for several days get out and use opioids at the same level they used before incarceration, they are at a much higher risk of dying than if they were using marijuana or cocaine. “So, that’s something that’s very different about this particular drug cycle,” he pointed out. “[I]t’s the lethality that makes this what it is.”

In short, the lethality and increased production of synthetic opioids make it nearly impossible for local communities, both rural and suburban alike, to get ahead of the problem. However, the policies put in place by state and federal lawmakers do not always help these communities in the ways they are intended. Even though policymakers have increased access to treatment beds and invested dollars in alternatives to incarceration, local governments still struggle to find qualified staff. “This is the frustration of the treatment programs,” one provider told us. “They keep expanding access to treatment but you can’t find a nurse practitioner to prescribe Buprenorphine. Programs fight over them because they’re so minimal. So how do you get good results if you can’t staff a freaking program?”

What Can We Do about It?

People on the frontlines of the opioid epidemic are frustrated. They feel like they are working harder and harder but still falling behind. Parents are angry, telling us if opioid misuse and overdose deaths are truly a national epidemic, then policymakers ought to treat them that way.

To make a meaningful difference, local governments across the state will need not just more resources, but the right kind of resources. For example, both government and nonprofit providers have a hard time hiring and retaining qualified staff. On the one hand, they aren’t able to pay enough. But on the other, there’s a shortage of people with the degrees, training, and experience required (often by law) to do the job. More money would likely ease the problem, but it wouldn’t necessary solve it. And other, more targeted solutions that incentivize people to get specialized degrees in counseling, nursing, or social work and training in psychiatry (especially child psychiatry) could also help.

| What Can We Do about Rising Opioid Death Rates? Two Findings: | ||

| 1. Local governments across the state need not just more resources, but access to the right kinds of resources. | ||

| 2. We need to think systematically about the kinds of outcomes that our current laws and policies incentivize. For example, under current law, it's much easier for doctors to prescribe opioids than medication-assisted treatment to treat addiction. | ||

Even in counties with more services, admission criteria at treatment centers and length-of-stay restrictions, which limit insurance to thirty days of treatment, make it difficult for people to access services even when beds are available — creating the illusion of services without effectively addressing the problem.

If we are serious in our commitment to ending the opioid crisis, then state and federal policymakers must listen to what local communities are up against and target their investments accordingly.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Katie Zuber is the assistant director for policy and research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Patricia Strach is the deputy director for research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués is a research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

READ THE SERIES

The Rockefeller Institute’s Stories from Sullivan series combines aggregate data analysis with on-the-ground research in affected communities to provide insight into what the opioid problem looks like, how communities respond, and what kinds of policies have the best chances of making a difference. Follow along here and on social media with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.