Rockefeller Institute of Government President’s Note:

Every 20 years, New Yorkers have the chance to vote on whether to hold a constitutional convention (known as a ConCon). The next vote will be held this November. If the voters approve a convention, delegates will be elected in November 2018, and the convention will open in April 2019. As the vote fast approaches, the Rockefeller Institute will continue to provide New Yorkers with information in various forms: public education sessions, publications, and debates. Please follow on Twitter or sign up on our website for all the latest information.

Today’s piece by Peter Galie and Christopher Bopst continues a series of pieces between pro and anti-ConCon experts. We hope the dialogue provides insight to help inform voters come November.

Part II: Criticisms of a Constitutional Convention (Read Part 1)

New Yorkers have a legitimate concern about politics as usual in the state, with the same three men sitting in a room making all the state’s decisions behind closed doors. Opponents of a constitutional convention make the argument that the process for selecting delegates, which in part resembles the process by which legislators are chosen[2], will enable “insiders” to dominate a convention, creating a duplicate forum for inaction when we already have one in our legislature. Why, they ask, should we expect anything better from a convention run by the “same old politicians”? They say that today’s political climate would make any convention a waste of time and money that could be spent more productively.

However, in light of the facts and previous conventions, the critics of the convention are wrong. Specifically, we explore three criticisms leveled against holding a constitutional convention.

- A constitutional convention is so similar to a legislature in the way it operates as to make its efforts duplicative of the legislature.

- Past conventions produced more of the same or so little that they were a waste of time and money.

- Past conventions were dominated by elected officials (legislators and judges).

Why a Convention Is Different Than a Legislature

One argument critics make against holding a constitutional convention is that it is similar to a legislature in the way it operates, thus making its efforts duplicative of the legislature. However, there are important differences between the state legislature and a constitutional convention. A constitutional convention:

- Is a unicameral body, so there is no need for passage by multiple houses and the attendant reconciliation required between the two houses.

- Is autonomous and transitory because it is called for a specific purpose and goes out of existence when that purpose is accomplished. This frees delegates from the pressures of re-election campaigns.

- Does not use a seniority rule for the appointment of chairs and leadership.

- Allows judicial, executive, and local government officials to participate jointly in its deliberations. Personnel are not separated into three branches as they are in state government.

- Limits the power of political leaders and parties. Convention officers do not have the political and legal influence that leaders of the state legislature wield. They cannot bury the proposals of maverick members in committees. Future committee assignments cannot be promised, and no local project can be initiated or delayed. As the leading scholar of the 1967 convention writes about that event: “leadership was generally much more constrained than normally would have been the case in the legislature.”[3]

- Has no institutional memory. Throughout New York’s history, there have only been a handful of delegates that have attended multiple conventions. Nearly all of the delegates to a 2019 convention will be new to the game. No delegates will exert special influence because of their experience in a prior convention (last held 50 years ago).

- Proposes only constitutional changes and focuses exclusively on that task. A convention engages in none of the other activities and exercises none of the responsibilities that are part of the state legislature’s duties, such as adopting a budget and the day-to-day business of governing.

- Has less demanding procedures for constitutional revision than the ones imposed on the state legislature. Constitutional amendments in New York that are initiated by the legislature must pass two separately elected legislatures; a convention requires only single passage by that body.

- Contains a mix of (senatorial) district and statewide delegates (there are 15 delegates selected at large). As opposed to a legislature, in which all delegates are representing local interests, a convention combines both local and statewide interests.

These differences contradict claims about the similarities of the two deliberative bodies. We now turn to the question of whether past conventions have produced meaningful reform.

Past Conventions Have Been of Great Value in Creating Our Constitutional Tradition

Many convention opponents assert that previous conventions have been boondoggles — do-nothing events that have squandered taxpayer money on partying while fattening up pensions, but producing little or nothing of value.

The best test of this claim is readily available: What did past conventions produce?

The 1821, 1846, 1894, and 1938 conventions, all of whose work was approved in whole or in large part by the voters, had their share of sitting or former legislators and judges. Yet nearly every right and most of the important constitutional reforms that we now look at with pride were the products of these conventions.

Here is a partial list:

- The state bill of rights;

- Environmental protections (the “forever wild” clause preventing state forest lands in the Adirondacks and the Catskills from being developed);

- The Education Article, which has been interpreted to provide the right to a sound basic education;

- The requirement that the state provide aid and care for its needy;

- Provisions encouraging the state and municipalities to provide low-income housing for their most vulnerable residents;

- A bill of rights for organized labor;

- The state’s equal protection clause;

- Constitutional protection for public employee pension benefits; and

- Protections against illegal searches and seizures.

The very constitutional protections opponents use to scare people from approving a constitutional convention happened because we held conventions! In the absence of conventions, would these cherished rights and policies be in the constitution? We wouldn’t bet on it. Since the state’s founding, conventions have had a much stronger record of creating and enhancing rights than the state legislature. Although we cannot predict what a convention will or won’t do, we have no evidence whatsoever to believe that a convention in 2019 would undo this strong tradition.

Our last constitutional convention, held in 1967, continued the state’s tradition of providing additional rights. That convention proposed a new constitution (ultimately rejected by the voters)[4] that included, among others, the following reforms:

- An independent redistricting commission;

- Suffrage for those 18 years or older;

- A more equitable school funding formula;

- Prohibition against discrimination based on sex, age, or handicap;

- A constitutional provision protecting clean air and water; and

- Reduction in the length of the document by 50 percent to 26,000 words.

In the face of these proposals, we think it is difficult to contend that conventions have been do-nothing boondoggles. Conventions have brought about remarkable transformations despite the inclusion of former politicians, legislators, and judges.

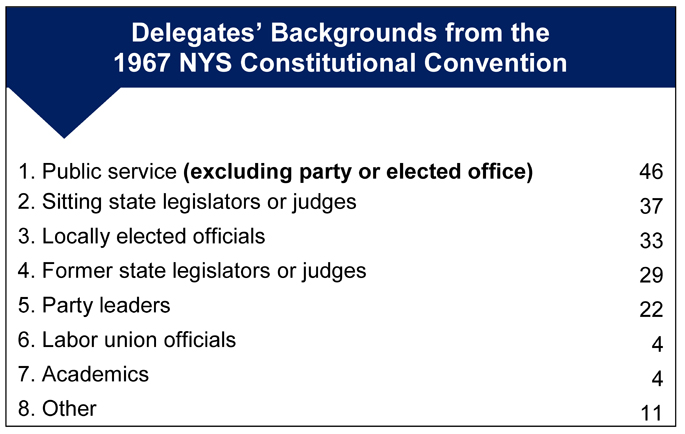

Conventions Have Not Been Dominated by Political “Insiders”

Contrary to popular misconceptions pushed by opponents of the constitutional convention, elected officials have not dominated past conventions. Of the 186 delegates to the 1967 convention, only 13 (7 percent) were sitting legislators and 24 (13 percent) were sitting judges — hardly dominant and nowhere near a majority. If we include former elected legislators and judges in our numbers, the total rises to 66 delegates, slightly more than one-third of the body.[5]

There are good reasons, however, for not lumping together former and current elected officials. If the claim is that a convention will not do anything differently than the legislature because it will be dominated by legislators, we would have to assume that former legislators — even though no longer subject to the rules, norms, and sanctions of that body, and not under any pressure to be re-elected — will, nonetheless, behave as if they were still legislators. This strains credulity and common sense and does not comport with the actual behavior of legislators. Who has not observed the willingness of former legislators to speak out or take positions on issues that, while legislators, the constraints of party, legislative norms, and need to be re-elected counseled silence? Branding former legislators and judges as “insiders” without closer analysis papers over real differences, especially on the important issue of delegate independence.

To our argument that legislators and judges, former and current, did not constitute a majority of the delegates, opponents might reply: “The term ‘insiders’ includes not just former and current elected officials, but local politicians like mayors, county attorneys, supervisors, local legislators, and nonoffice holding political party leaders.” Of course, broadening the categories of those termed “insiders” to include these additional categories, by definition, increases the number of “insiders” at a convention, but it also takes the sting out of the conclusion opponents have drawn from their presence.

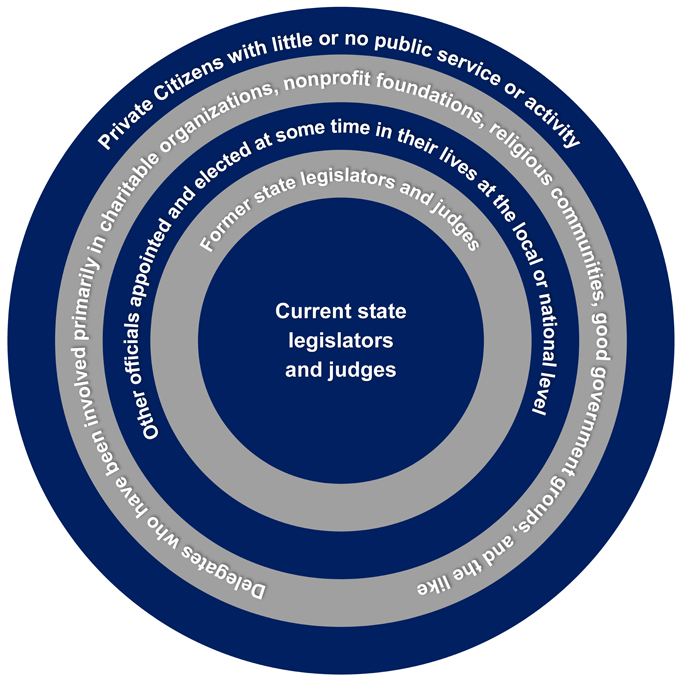

Let’s locate each category of delegates in one of a series of five concentric circles:

The first three circles contain the “insiders,” broadly interpreted. However, lumping these individuals together ignores crucial differences among them — differences that suggest much more diversity of opinion and independence than the homogenizing pejorative “insider” implies.

Should we label as insiders both a legislator who served one term and left because she thought she could promote legislative reform better from the outside and one who has been in the legislature for 25 years? How helpful is that? Would you put them in the same category?

Ask yourself: Should a former judge with a sterling record and the admiration of the community be tainted with the label “insider?” How about a former legislator who served with distinction? Consider a judge who sat on a City Court having retired 30 years prior to serving as a delegate. Isn’t it likely that that judge will have perspectives and experiences quite different from a currently serving Court of Appeals judge? Or consider a former governor or attorney general who, since retiring, has been an active member of a good government group like the League of Women Voters or Common Cause. Should we dismiss as “insiders” past or present local officials who have earned the trust and respect of their constituents?

Do we do them a disservice by labeling them with the presumptuous and denigrating label “insider?” Is that label at all helpful? Should we call such labeling by its proper name: propaganda?

If there are delegates at future conventions who have distinguished themselves in public life and earned the esteem of the voters who chose them as delegates, should we fault the process for producing such results? Would we want a convention filled with delegates who had no political experience or familiarity with decision-making in democratically organized forums? Between the two ends of the spectrum — a convention dominated by current legislators, judges, and party leaders and one dominated by political neophytes — there is a middle ground. That middle ground is revealed by examining the background of the delegates to the 1967 convention:

What is most striking about this list is that the largest number of delegates were in the public service category. These delegates were most notable for their public service, and not by extensive party leadership positions or elected office. They were individuals who had distinguished themselves as citizens.

Even among the minority of sitting and former legislators, profound and significant differences existed. Here are some examples.

These delegates were from:

- different parties (Democratic, Republican, Labor, Liberal);

- different parts of the state (upstate, downstate, etc.); and

- different courts (ranging from justice courts to the Court of Appeals).

Some former legislators and judges had been off the bench or out of legislative office for over a generation. Most importantly, the individuals occupying each circle did not think alike on all or most of the issues at the conventions.

Social science research, not to mention our daily experience, recognizes that the loyalties of men and women in public life are diverse; obtaining office under the label of a major party does not mean that person is in harmony with all those who likewise profess that label. To assume that these demographic characteristics (age, race, religion, ethnic background, and life experiences) would not create a diversity of opinions is naïve, if not willfully ignorant.

What Insiders Will Share

What delegates with lengthy careers in public service and extensive political experience do share — and what we believe they would ensure — is that we will have a convention comprised of delegates who are:

- Familiar with our constitutional system of local, state, and national governments; and

- Committed to our constitutional values: the rule of law, an independent judiciary, a viable legislature, and the rights and policies New Yorkers cherish.

Such delegates are the best defense against the charge that a convention will open Pandora’s Box and threaten our constitutional values.

When we move beyond the breezy cynicism of “the insider’s game” phrase, the argument falls of its own weight. Let’s call this argument what it really is: an argument made by insiders!

Forthcoming in Pace Law Review

Notes

[1] New York needs a state constitutional convention. The state’s most recent convention was held in 1967, and calls for a convention were rejected in 1977 and 1997. We believe a convention is the only way to achieve meaningful and necessary solutions to the state’s systemic problems. This multipart article addresses both why we believe a convention is necessary and attempts to respond to some of the most common arguments against a convention.

[2] If the convention call is approved in November 2017, delegates will be elected in November 2018. Three delegates will be elected from each of the state’s 63 Senate districts (for a total of 189) and 15 delegates will be elected statewide, making a total of 204.

[3] Henrik N. Dullea, Charter Revision in the Empire State: The Politics of New York’s 1967 Constitutional Convention (Albany: Rockefeller Institute Press, 1997): 18-9.

[4] The constitution submitted by the 1967 convention, although forward looking in many respects, was rejected by voters. One of the main reasons for the proposed constitution’s defeat was the controversial repeal of the existing prohibition against the use of state funds for parochial schools. By submitting its work as a single, “take it or leave it” constitution, the 1967 convention eschewed the prudent decision of the 1938 convention to submit its work in nine separate proposals. This proved to be a fatal mistake.

[5] At the 1938 convention, 73 delegates (approximately 45 percent) had either current or past state legislative or judicial experience. In 1967, the comparable figure was 35 percent, down 10 percent.

z

z